The Great Barrington Airport offers lessons to those interested in aviation as a hobby and, in some cases, a career with the airlines. Some neighbors worry about the flight school and their safety.

∎ ∎ ∎

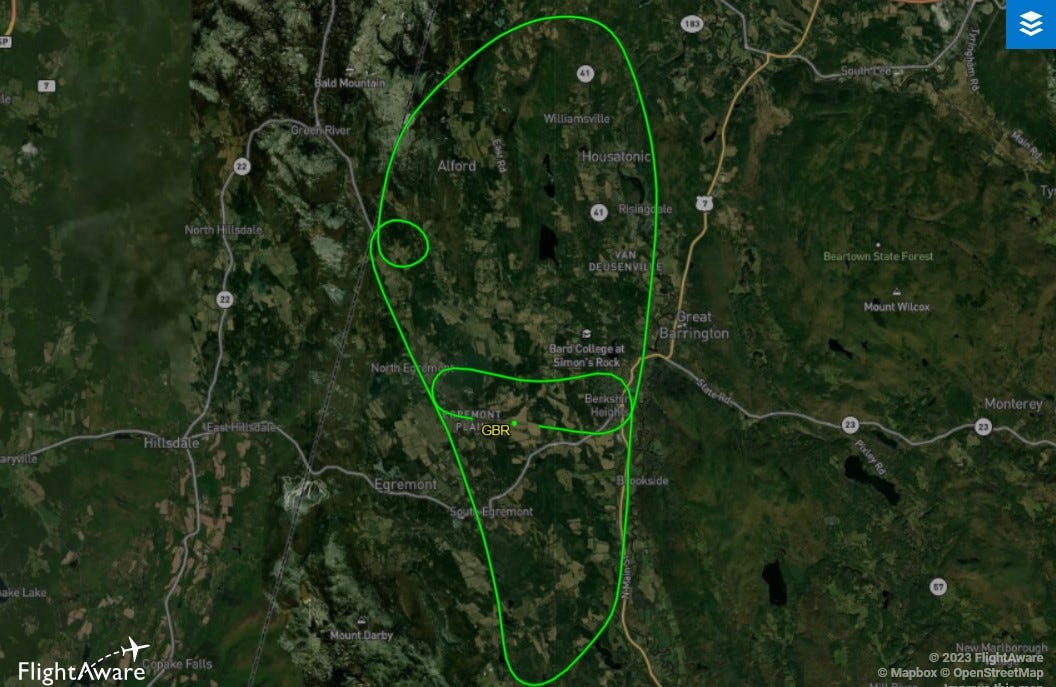

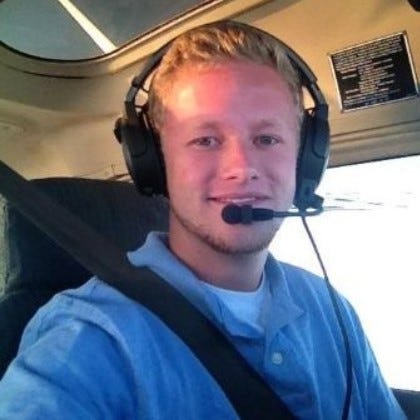

One morning last July, as we crossed over the border between West Stockbridge and Alford, Joe Solan, a 24-year-old flight instructor and the operations manager at Great Barrington Airport (GBR), suggested that I look around and enjoy the view.

Solan was in the right-hand seat of a yellow 1966 Piper Cherokee trainer known around GBR as the “Banana Berry.” I was squeezed into the left seat, hands gripping the controls, knees bumping the instrument panel inside a too-small-for-a-tall-guy cabin, eyes darting between various gauges and the nearby airspace—and sometimes forgetting that the purpose of the whole enterprise was to do what Solan gently reminded me to do.

And not just Solan: In his 1998 book, “Inside the Sky: A Meditation on Flight,” the writer and pilot William Langewiesche suggests that “flight’s greatest gift is to let us look around, and when we do we can find ourselves reflected within the sky.” Langewiesche, whose father was a test pilot who authored a famed 1944 book about flying technique, “Stick and Rudder,” later said in a published interview that “the pattern of our lives” is easier to see when looking down from a few thousand feet.

Among other themes explored in the book’s poetic essays, he frames aviation as a perspective-giver that can help us see a host of things in a new light. At higher altitudes, as those patterns on the ground blur and the view produces feelings that evolution hasn’t prepared us for, Langewiesche says our thoughts naturally turn inward.

That kind of exploration wasn’t on my hyperactive mind as we banked to the southwest toward Egremont, flying about 1,700 feet above the ground. Not that I wasn’t thinking about many things during our 25-minute flight. At times, it was reminiscent of learning to drive a stick-shift: paying conscious attention to things that, with a little practice, would soon become second nature. In the air, knowledge, experience, and physical sensation merge with the skill to apply an aircraft’s controls in response to things seen and felt. And, at a mundane level, to know which way to turn a particular knob to produce a desired result.

Solan kept things on track as we flew above the southern Berkshires, managing the plane’s rudder with pedals at his feet. He occasionally suggested that I adjust our speed or altitude. And, of course, he was ready to take over the dual controls if needed—something that should, at least in theory, put a student pilot at ease. At his direction, my hands moved between steering yoke and throttle control, which, in the Banana Berry, is a small knob that’s pulled out or pushed into the instrument panel. Though I kept forgetting which direction produced more engine power or less.

Occasionally he’d ask me to “trim” the aircraft using a small handle above my head that, when turned, adjusts the plane’s rear control surfaces. Properly trimmed, the Piper flew steady and true. My hands even came off the controls like a kid cruising hands-free on his bike down a long hill, enjoying the thrill and freedom that came, back then, from parental rule-breaking, and that was now delivered by the feeling of smooth, level flight.

There was much to see on that July morning. The mid-summer sky was clear with only a slight haze. To my untrained eye, the ground below seemed a blur of various shades of green carpeting interrupted by inky-black bodies of water and similarly dark crisscrossing roads. With focus and effort, I could recognize a few landmarks in the landscape below. Overall, what I saw looked like something that generations of aviators had—unquestionably to their benefit—never seen: a slow-moving, label-free Google map.

There wasn’t much to hear, though, over the combined roar of engine and propeller in the poorly insulated cabin of a half-century-old plane. Solan and I were shoulder-to-shoulder but communicating via headsets and microphones. When the flight was over, for a time, my ears felt as if I’d just left a rock concert.

Solan has given countless lessons to new and prospective pilots and has developed, no doubt, a certain patter. “This is the view from my office window,” he said as we performed a slow circle in the sky near my home. It’s not likely the first time he’s said that to a pilot-trainee, but it surely gets desk-jockeys to ponder alternate ways to make a living—or at least consider committing time and significant expense to aviation as a hobby.

As we re-entered the airport’s local flight pattern, I tried to locate other planes nearby—a critical safety skill, even in the vastness of three-dimensional airspace. Meanwhile, Solan prepared for our final approach and landing. While I’d largely been in charge during takeoff and much of the flight, getting the Piper and both of us safely back on the ground was entirely in Solan’s hands. As the aviator’s mantra goes, “Takeoffs are optional. Landings are mandatory.”

This was my so-called “discovery flight,” a $99.00 introduction to flying a single-engine, propeller-driven aircraft that Berkshire Aviation Enterprises (BAE), the private owner of the public-use airport, flight school, and maintenance operation on Egremont Plain Road, offers to anyone interested. Though it was not my first time behind an airplane’s controls: Twenty years ago, a friend took me up from a small airfield outside Washington, D.C. and let me fly his Cessna to Baltimore and back.

Even then I wasn’t new to aviation: My teenage years included reading Aviation Week & Space Technology magazine cover-to-cover—more for the space technology than aviation, to be candid—and spending hours in front of a Radio Shack computer playing T80-FS1 Flight Simulator, an early video game soon licensed to Microsoft. It featured graphics so rudimentary they would likely blind a 21st-century gamer. But if you had a little imagination and could forget you were controlling engine power with arrow keys, it was possible to get lost in the fantasy. It wasn’t always easy: “A flick of the B key will give one notch of up elevator,” noted a review in 80 Microcomputing magazine, a nerdy bible of the early personal-computer age. More than 40 years later, when I looked around the cabin of the Banana Berry, there was no keyboard or B key in sight.

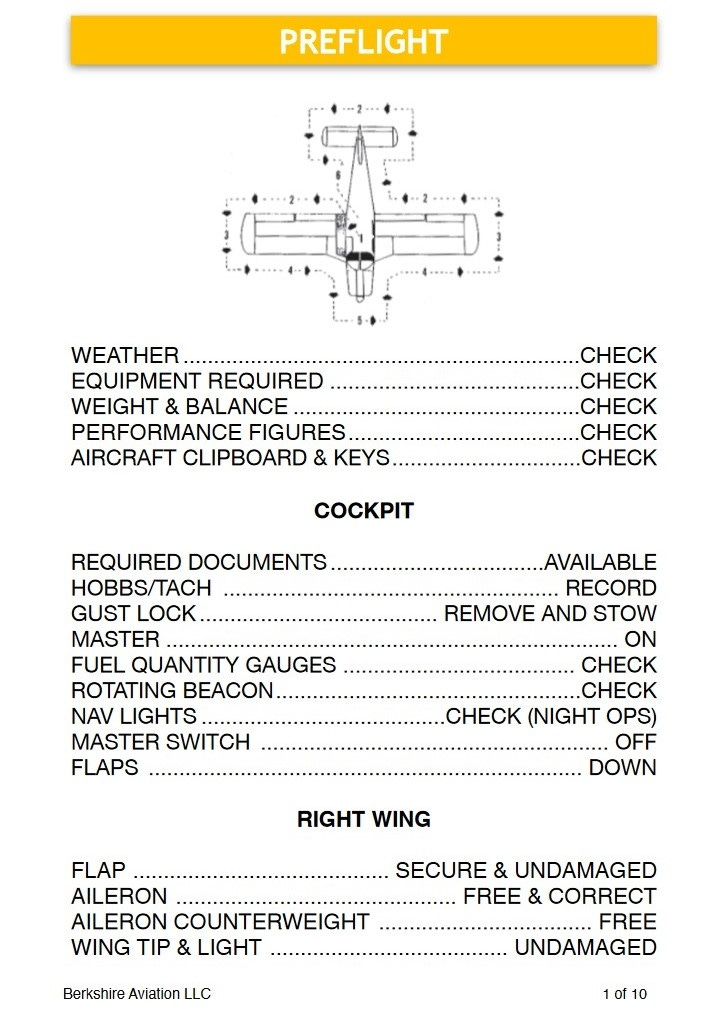

Numerous preflight safety checks

Before we taxied to the western end of the airport’s single 2,579-foot runway and lifted off on that half-hour flight, Solan walked me through a long list of preflight safety checks. We began by opening both sides of the engine compartment to check for fluid leaks and ensure all wires were secure. We examined the propeller and other components for any damage; tested flight-control surfaces for smooth movement; confirmed that external lights were functioning; checked the landing gear and tires; and examined fuel samples for water and sediment—two bitter enemies of smooth and safe engine operation.

As we prepared to climb inside, the Piper—manufactured a year before my birth—struck me as an old, simple, and fragile machine. It is powered by an engine designed in the middle of the last century. To some, that’s concerning. But others see its age as comforting evidence of a reliable design that has proved its mettle, whose replacement parts and maintenance procedures have been refined over decades—and, importantly, created generations of mechanics who have mastered its details.

During our preflight examination, I noticed that the ailerons on the rear edge of the wings—in the air, they push each wing up or down to turn the plane—were attached in several places with what seemed to be inappropriately tiny jackscrews. Jeff Dodge, BAE’s longtime chief mechanic, later told me he’s never seen one of those screws fail, which was a post-flight relief.

Inside the plane, a set of laminated checklists detail how to prepare the airplane for flight. Solan and I ran through them in call-and-response fashion as we powered on and configured the plane’s various systems. Minutes later, engine running and propeller turning, we taxied to the end of the runway to prepare for takeoff with no tray tables to lift, seatbacks to raise, or luggage to stow. All told, BAE’s printed preflight checklist for the Piper Cherokee includes more than 100 items; many pilots also have detailed checklists loaded onto iPads they also use for flight planning and navigation.

During a few dozen visits to the airport since last summer, I watched students complete their preflights countless times. In addition to required FAA safety inspections and maintenance schedules, it means that BAE’s training planes are scrutinized by many sets of eyes, multiple times per day.

Still, in the wake of two flight-school-related accidents last summer (one from engine failure on takeoff and another, more serious crash caused by a student’s fuel-management error), questions about safety have continued as part of the legal, zoning, and community conversation about the airport and its busy flight school.

In their advocacy, the airport and its proponents point to BAE’s flight school as an important vocational-training opportunity in the region, at least for a few. And they argue that its safety record is exemplary, even with recent mishaps. Some who have long lived in the airport’s residential neighborhood see it differently, convinced it’s the wrong location for, among other things, an increasing amount of student-pilot flying. They fear that will mean more danger to those on the ground, pointing to eight accidents at or near the airport since 2008 that the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) found were nearly all due to pilot error.

As noted in part six of this series, questions about flight school intensity and related safety concerns are not just an issue here: In communities across the country, flight school activities have increased over the last several years from pandemic-era interest in flying—when other activities were prohibited or limited—and in response to the airline industry’s current need for additional pilots. That has fueled a growing national focus on airplane noise, safety, environmental concerns that include leaded aviation fuel, and other issues. Many of those questions and concerns have been raised in front of the Great Barrington Selectboard during its numerous airport-related hearings since 2017, ending, for the moment, with a 4-1 vote this month to make the airport a conforming use under the town’s zoning bylaw.

A history of cultivating local media

My flight with the airport manager was certainly not the first time a local writer took to the Berkshires sky and wrote about the experience. Historian Bernard Drew took a lesson as part of a 1993 Berkshire Eagle story about the county’s airports in Great Barrington, Pittsfield, and North Adams. He described having a “white-knuckled grip on the controls” and feelings that “fluctuated between exhilaration and sheer terror.” Walter Koladza, the former test pilot and flight instructor who owned the airport from 1945 to 2004 and after whom it is now named, later told Drew that is a familiar range of feelings for a newbie. “A shot of Scotch will help,” he said with typical—and highly quotable—bravado.

Indeed, based on a review of hundreds of articles about the airport since the 1930s, Koladza was extraordinarily savvy about cultivating local journalists to advance his business interests. That was particularly true among those who worked for the county-wide Eagle, which employed a succession of aviation-interested and GBR-friendly reporters, columnists, and editors. (DISCLOSURE: I wrote a regular column for the Eagle from 2003 to 2011.)

One Eagle reporter, Frank V. McCarthy, took flying lessons at GBR in 1953 and wrote an extensive five-part series about the experience. In the first installment, he explained how the project came to be: “Newspapers should enlighten the public about the ease and safety of flying a small plane,” Koladza reportedly told him during a visit to the airport. “And the best way to do that would be to take an ordinary newspaper reporter who had never flown in his life, teach him to fly and have him do a series of articles on it.” McCarthy eagerly took the bait, boasting in print that he was “getting $250 worth of flying lessons for nothing.” (DISCLOSURE: The Berkshire Edge paid for my $99.00 introductory flight lesson.)

McCarthy, who would go on to become the Eagle’s managing editor, recalled his lessons and the article series years later, in a 1998 interview. He said he completed a solo flight during his eighth lesson but “quit before I got my license.” He concluded, “If I had kept it up, I’d probably have killed myself.”

Over the years, local reporters and columnists served as a veritable marketing department for the airport, printing Koladza’s claims with little fact-checking and publishing glowing profiles of his growing operation. (Koladza was also a frequent Eagle advertiser.) As reported in part two of this series, press coverage since the early 1930s generally aligned with the town’s municipal and business leaders’ interest—financial and otherwise—in the airport.

The cost of flight lessons

Solan estimated that three-quarters of those who try a discovery flight take some additional lessons, though not everyone secures a private-pilot’s license, trains for additional certifications, or buys a plane. Students can’t solo until they’re 16 years old—many try to do so on their birthday, weather permitting—and must be 17 years old before an FAA-licensed examiner can take them up for their practical test, known as a check ride. Certifications that require additional training include an instrument rating, to allow flying in all weather conditions and without visual reference to the ground or horizon; commercial, to carry passengers for pay; proficiency flying multi-engine aircraft; certified flight instructor; and the airline-transport pilot (ATP) certification, required to fly large jets for the airlines.

Flight training is expensive, particularly if the goal is to acquire the advanced certifications and hours of flight time required for an airline job. Instruction at GBR runs upwards of $200 per hour, which includes $50 for the instructor’s time and $150 per hour for rental of one of BAE’s Piper training aircraft, based on recent rate cards. A basic private-pilot’s license normally requires at least 40 hours of airborne training.

Typically, students train for 60 to 70 hours before their check rides, Solan told me, so the cost can easily exceed $10,000. Nationally, the average cost of earning the initial private-pilot’s license is between $10,000 and $20,000. In addition to time in the air, students learning at GBR also participate in ground-school lessons—especially when bad weather keeps them from the air—in a couple of small classrooms in the airport’s administration building, which also houses a small computer flight simulator.

BAE has sometimes awarded scholarships to help students defray the cost of their training. In 2022, it granted a total of $15,300 to four students from communities in New York, two from Connecticut, and one each from Pittsfield and Becket in Massachusetts. Earlier this year, it announced plans to award two grants of $15,000 each to “individuals aspiring for a professional aviation career.”

It is unclear how many students take flight lessons at GBR right now—or at any given time. It’s also unknown how frequently each student takes a lesson. At various times since last summer, Solan and his father, Rick, the retired American Airlines pilot and longtime instructor who is the airport’s majority owner, told me they have around 25 students.

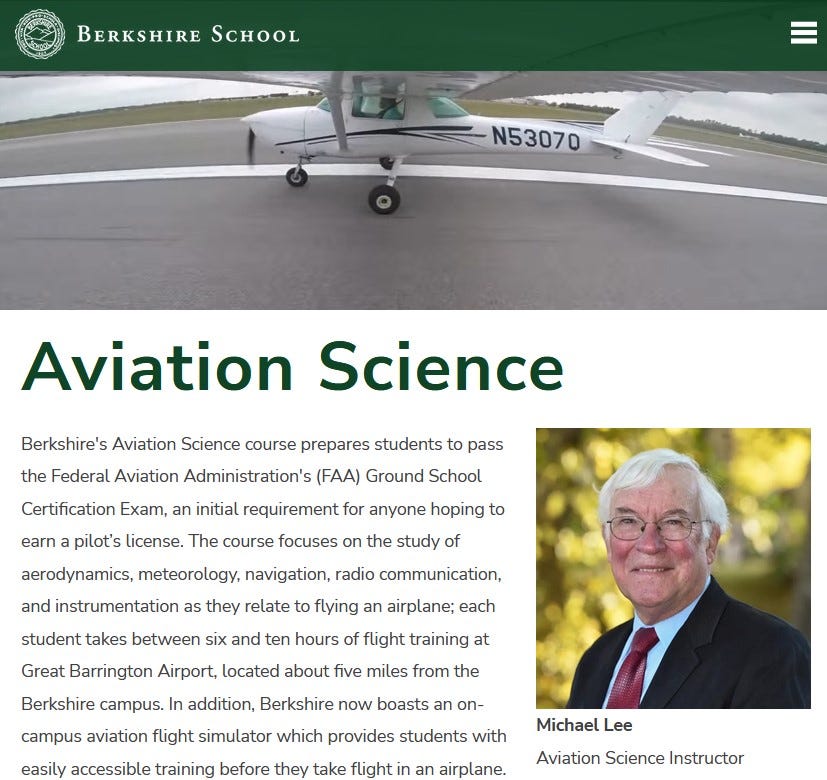

That total doesn’t include half a dozen or so from Sheffield’s private Berkshire School who take lessons on Sunday mornings during their spring semester. That flight training is underwritten by The Hans Carstensen Aviation Endowment, named for a Berkshire School alumnus, according to Michael Lee, a local pilot and educator who helped re-establish the school’s aviation-science program in 2010. There are no comparable programs currently offered by Berkshire County’s public high schools.

During the Selectboard’s recent hearings, BAE was asked to provide details about flight school enrollment and activity. But that information was never provided, even as the town’s attorney, David Doneski, advised the board to benchmark with specificity the airport’s current level of activity. Doneski said it was essential so future Selectboards can evaluate whether operations at the airport exceed what BAE and the board agreed would be no growth without additional town approvals—or as the airport’s attorney, Dennis Egan, said repeatedly, to constrain the airport to “what you see [today] is what you get.” (The special-permit process, the conditions imposed, and what may come next is examined in the final installment in this series.)

It would have been easy to provide those details: BAE uses a popular web-based flight-school-management application called Flight Schedule Pro, which, among other features, creates schedules for instructors, logs the flight time of all BAE aircraft used for lessons and rentals, and can produce a host of detailed reports. (Pilots and students can log into BAE’s system to make appointments for lessons and rentals.)

Flight Schedule Pro is used by flight schools across the country for billing, tracking student progress, as well as to monitor aircraft-maintenance milestones. Rick Solan told me that one benefit of the system is that it won’t allow booking an aircraft for rental or a lesson if the plane’s usage shows it’s due for maintenance or inspection. That includes an FAA-mandated, every-100-hour inspection for all training aircraft, which BAE performs using FAA guidelines for the more comprehensive annual inspection.

To the airlines

So how does a career-minded flight-school student go from discovery flight to private-pilot’s license, to additional certifications, and then perhaps to the airlines? A bachelor’s degree is not required, though many believe it’s advantageous, particularly during times when hiring by the airlines is less frenetic than it is today. “They were locking themselves out of good pilots,” Rick Solan told me recently about the change, which he said has opened the door for more people to pursue aviation careers.

Earning a bachelor’s degree and flight certifications from a four-year aviation school like Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University can cost more than $200,000, but it reduces the flight-time requirement to apply for that essential air-transport-pilot certification from 1,500 hours to 1,000 hours—the key metric for those aiming for the airlines. That includes a minimum of 500 hours of “cross-country” flight time, which means travel to a point at least 50 miles from the original point of departure; 100 hours of nighttime flying; 75 hours flying on instruments; and at least 250 hours as pilot-in-command of an aircraft. Accelerated, non-degree training programs at schools like ATP Flight School can cost $100,000.

Two who made the leap

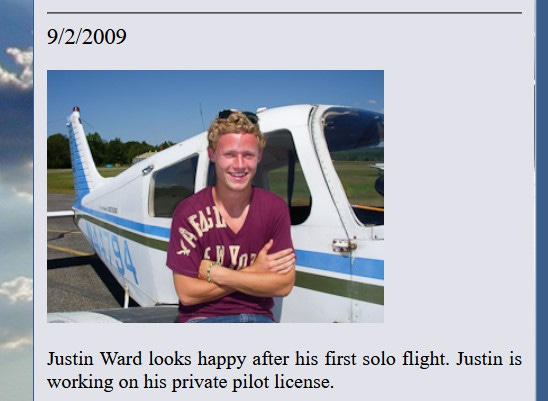

Among those who trained or taught at GBR and then went on to the airlines is Justin Ward, a 31-year-old Delta Air Lines pilot who grew up in Great Barrington and today flies the Boeing 737 to destinations in the United States and the Caribbean. (Though he grew up here, he now lives in Fairfield, Conn.) He told me in a December interview that he flies about 15 days a month—and that he loves his work. “If there’s any job for me, I think this is definitely it,” he said. “Just being out traveling, seeing different parts of the world, and then getting to share that with my family. It’s definitely a job I love.”

His father, who also took lessons at GBR, gave him a discovery flight as a 15th-birthday present. A year later, he started training for what he decided would be his career. He took lessons primarily with longtime BAE flight instructor Peggy Loeffler. With advice from her and Rick Solan, he considered various paths to an aviation career, including through military service. In the end, he chose college and a related degree. “For me, the college route seemed the best and fastest [path] to the airlines, which was the end goal,” he said.

Ward attended Embry Riddle, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical science in 2014 and acquired many of his flight certifications. He next logged hours with time-building jobs towing advertising banners above beaches from Rhode Island to Bridgeport, Conn., and sometimes in Florida during busy spring-break periods. He also worked as co-pilot of a seaplane that flew out of New Haven.

Because he attended an FAA-certified “Part 141” aviation-training program, he needed 1,000 hours of flight time to secure his air-transport-pilot certification and apply for an airline job. Once he reached that milestone, he was soon hired by Endeavor Air, the regional carrier headquartered in Minneapolis and owned by Delta since 2012.

Ward said there was some luck involved. “The aviation industry in general is really all about timing,” he told me, pointing to ups and downs in the economy, various waves of pilot retirements and hiring sprees, and recently, the impact of the pandemic. He was scheduled to move from Endeavor to Delta in April 2020, with a confirmed date for entry into Delta’s training program. The pandemic put that on hold for what at first seemed to be an indefinite period, but which only caused a four-month delay.

Not surprisingly, Ward points to having an airport in his hometown as a catalyst. “If I didn’t grow up near Great Barrington Airport, I probably wouldn’t be flying for a career,” he said. “It’s like a bug you catch and it’s all you want to do.” When he took his discovery flight at 15, he couldn’t yet drive a car. “And here I was, flying an airplane around my hometown. I just remember being in disbelief.” During his senior year at Mt. Everett Regional School in Sheffield, he was allowed to create a for-credit internship at GBR, where he helped with “just about anything,” he said.

Ward said there are some advantages to training at a small airport, particularly the speed with which a student can get into the air and begin their lesson. He compared that to Daytona Beach, Fla., where he did some flight training while at Embry Riddle. He could spend 20 minutes on the runway just waiting to take off, he told me, and then spend 20 minutes flying to a sparsely populated practice area. That extra time makes training more costly. Conversely, that’s precisely what Great Barrington residents have told the Selectboard concerns them about the trajectory of BAE’s flight school: more locally intense flight operations over their sparsely populated rural neighborhoods.

A second career in aviation

One of Ward’s instructors at GBR was Ian Hochstetter, who flew with Endeavor before moving over to JetBlue. When we met for breakfast last August, he was on a day off from flying the twin-engine Embraer 190, which carries around 100 passengers. Like Ward, he also lives south of Great Barrington in Connecticut.

Hochstetter first learned to fly as a teenager in Danbury, Conn. and turned back to aviation after more than two decades working as a building contractor in a family business. His career redirection began in 2013 with a return to GBR to work as an instructor. The shift was sparked by some life changes, he told me, and at the time he found the aviation community at GBR to be “a nurturing environment.” Deciding to pursue a second career in aviation at GBR, he said, “was like coming to your grandmother’s house on Thanksgiving, the smell of the turkey and everything cooking. And you’re like, ‘I’m home.’”

Hochstetter has the calm, thoughtful confidence that airline passengers no doubt like to see when he steps onto an airplane and turns left into the cockpit. And like Ward, he truly enjoys his work. “What I love about being a commercial pilot is that I get paid really well for doing something that I love,” he said. “I love flying, I love the process of working with people … I’m actually happy getting in my car and going to work. I couldn’t always say that when I was a builder.”

Hochstetter’s father was a Vietnam-era helicopter pilot, so he grew up around aviation. “As a kid I would sit in my bunk bed with a fan in front of me and pretend I was flying an airplane,” he told me. And he found a community passionate about aviation at GBR, he said, from Koladza, to other pilots and instructors, to the Solans. “We love aviation. We love the people around it, the simple planes, and we like safely taking care of people.” Hochstetter’s 25-year-old son is also a pilot working toward an airline career.

He told me that he also likes the vibe of GBR compared to other airports that he said can be “shiny and glitzy and professional to a point where it’s cold.” He thinks the informal feel of the old-style airfield connects with young people who want to learn to fly—and who, he said, discover that it’s a serious operation even without that shine and glitz. “As far as value, and inspiring young folks, it’s really a great place. And I’m a testament to it,” he said.

Flight instructors and the airline hiring spree

Pilots aiming for the airlines frequently build needed hours by working as flight instructors, as both Hochstetter and Joe Solan, who plans to leave shortly for the airlines, did at GBR. All that time in the air, during which they’re considered pilot-in-command, counts toward what’s needed to get to the next level.

With today’s substantial demand for pilots—following 2020’s airline cost-cutting that included buyouts and early retirements—that race to 1,500 hours has raised concerns about the quality of instruction across the country. Indeed, several flight instructors told me they’ve seen an increase in the failure rate for those taking examinations for everything from private-pilot licenses to flight-instructor certifications. As the airlines draw in more of today’s instructors, less experienced ones are left behind to teach new pilots—and they, too, may be more focused on building hours than mastering teaching skills they don’t expect to use again.

The airlines’ current hiring spree also adds other pressures: Rick Solan told me that, when he counsels a career-oriented student, he points out that a year or two delay in reaching the airlines can have a lifelong impact on seniority. That means fewer options for types of planes to fly; lower pay; and, ultimately, less money earned for retirement.

Safety and flight training at GBR

With the increase in local flight school activity, neighbors have suggested that more takeoffs and landings by student pilots means increased risk of accidents near their homes. In response, the airport and its instructors insist their commitment to safety and quality instruction runs deep, advanced by a core group of longtime BAE flight instructors.

“The number one thing is making safe pilots,” Joe Solan told me in our first conversation last summer. “I want to make sure that when I send my student out for their check ride, they are not only going to pass the check ride proficiently, but afterwards, that I feel comfortable that they’re going to be able to take passengers and fly safely.”

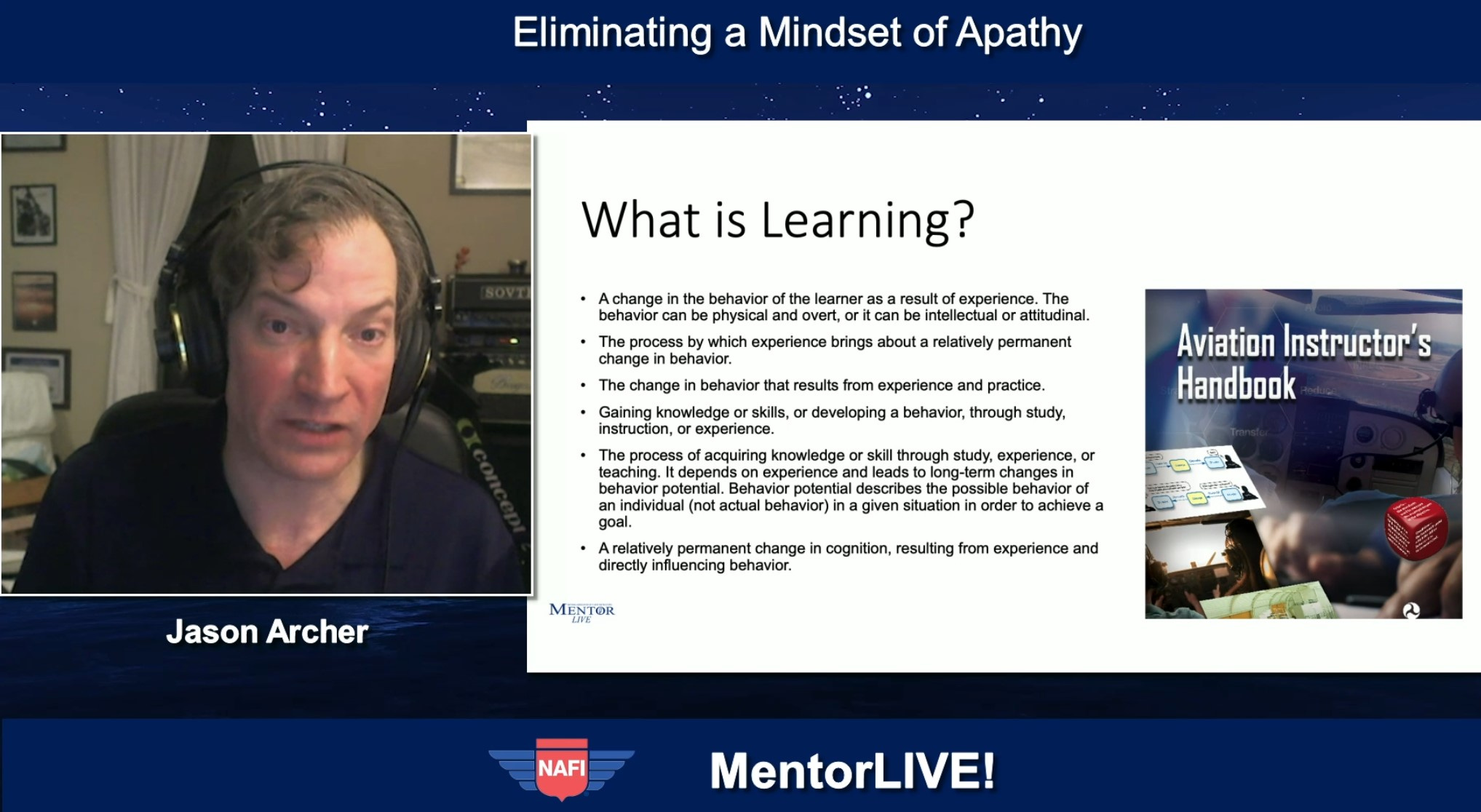

BAE’s chief flight instructor, Jason Archer, told me that safety is at the core of flight training at GBR. And that the airport has long had a more personal and holistic approach than what is offered at more “regimented” flight-school programs that aim to churn out professional pilots as quickly as possible.

“We have a good cadre of [instructors] who care about the people first and the flying second,” he told me in February. An astronomer and longtime teacher (during the week he runs a school planetarium in Connecticut and works at GBR on weekends), Archer has brought his love of teaching to his work in aviation.

We spoke not long after Archer presented a webinar on improving flight instruction, “Eliminating a Mindset of Apathy,” for the National Association of Flight Instructors (NAFI). It’s a subject he’s worked on for years: teaching the teachers, which he does in presentations at a popular aviation conference each summer in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, where he also works at a skill-building pilot-proficiency center.

Archer wants to combat an attitude he’s seen among some instructors, particularly at a time of rapid hiring by the airlines: “Let me do the bare minimum I have to do, check the boxes, and go off to the airlines,” he said. So, he’s been making presentations, like that recent NAFI webinar, in front of FAA officials, fellow instructors, and others nationwide with an interest in aviation safety and pilot education.

He described BAE’s approach to teaching, which is detailed on its website, as more flexible than other flight schools and able to account for students’ strengths and weaknesses while still covering all FAA required topics and skills. “We can work with a student one-on-one and help them get to be where they need to be,” he said. Even with that attention, Rick Solan told me that if after many hours of dual training, he doesn’t think a student can safely proceed to soloing and mastering necessary skills, he’ll suggest they pursue other interests.

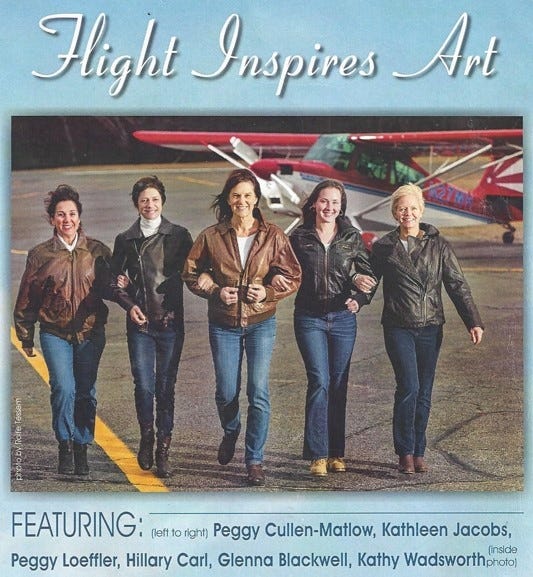

Peggy Loeffler’s advocacy for women in aviation

Peggy Loeffler, who has taught at GBR for nearly two decades, echoed that commitment to safety and skill mastery when I spoke to her last fall. “If you learn to fly here, you learn to fly at an airport with a short runway, with hills, trees, crosswind, all sorts of challenges,” she said. “And you’re trained well here. Those of us who are teaching are very committed, doing this because we love to do it.”

Loeffler’s father was a B-29 pilot and instructor during World War II and owned a plane while she was growing up. As a teenager, she was interested in an aviation career. But in the 1960s, opportunities were limited. “Women were not allowed in the military, they were not allowed in the airlines, and there were no astronauts,” she told me. “So, I would go to airports with my dad, and I wouldn’t see any women. Just older men like my dad.” He bought her a book about how to become a stewardess. “I read that, and I thought, ‘That’s not for me.’”

She gave up on aviation for a while. But in college, she stumbled into an aerodynamics class that was filled, she said, with “16 boys and me.” The physics professor teaching the class discouraged her, telling Loeffler that if she remained, she “shouldn’t expect any special treatment”—as if she needed any. She persisted and stayed in the class, which included designing gliders flown in a competition at semester’s end. “And mine stayed up [in the air] for 63 seconds. It was a school record, and stayed up longer than anyone else’s, and I got an A-plus.”

As described in part one of this series, Koladza declined to hire Loeffler in the 1990s when she was training to become an instructor; she said that Koladza’s “boy’s club” wasn’t ready for a female instructor. But she continued her training, subsidized by awards and scholarships from The Ninety Nines, the storied women’s aviation organization founded by Amelia Earhart and other women pilots in 1929. When new ownership took over the airport after Koladza’s death in 2004, she returned to GBR as an instructor. (BAE today employs two women as flight instructors.)

Her commitment to championing women in aviation is evidenced not only in her roster of female students, but also at the New England Air Museum in a permanent exhibit called “New England Women in Aviation”—something Loeffler spent 20 years researching and developing. “There’s no reason a girl should be discouraged from going into a classroom to study something she wants to study,” Loeffler told me. “So that’s why I feel very strongly about promoting aviation to young girls and other women.”

Today she teaches part-time at GBR and works as an FAA flight examiner across the region. Along with Berkshire School’s Michael Lee, she’s an evangelist for teaching high-school students to fly because of the benefits she says it delivers—even for those who don’t pursue it as a career. “Aviation provides these young people [with] a sense of responsibility, because there are many rules to follow,” she said. “And it’s a risk. You’re managing risks to the best of your ability. Everything is about safety. So you mix that responsibility with an incredible sense of freedom.”

Risks from flight training versus other flying

Is there more risk to those on the ground from flight-school operations than from other general-aviation flying? Despite testimony from Great Barrington residents about that concern, there was little discussion of safety or accidents during the recent special-permit hearings.

There is some helpful industry analysis. A 2014 study by the Air Safety Institute, a program of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), looked at accidents during flight lessons over a decade and found the overall rate of accidents of fixed-wing aircraft to be the same during lessons as non-instructional flights. Fatal accidents, the study found, were less than half as common during instructional flights than other flying.

But the study also reported that takeoffs, landings, and aborted landing “go-arounds”—core components of primary flight training—account for half of all training accidents. (Both of last summer’s accidents at the airport fall into those categories.) About two-thirds of those accidents took place during student solo flights, and 64 percent of accidents during student solos occur during landing.

Mechanical failure or loss of engine power accounted for 20 percent of accidents during primary training with an instructor on board. And while fuel mismanagement—the result of poor flight planning or incorrect operation of aircraft fuel systems—caused less than four percent of all student accidents, the AOPA report said it “remains a concern.” That is because of a much higher rate of serious injuries and fatalities from accidents caused by fuel-system errors.

In support of the airport’s special-permit application, AOPA, which is active as a pro-industry lobbyist in Washington and across the country, sent a letter to the Selectboard in February. It addressed what the airport’s advocates told me were misconceptions advanced by airport critics on issues from leaded aviation fuel to the safety of older aircraft to noise abatement.

On safety issues, the letter pointed to a downward trend in the overall number of accidents per 100,000 flight hours, to 4.69 in the less busy 2020 pandemic year. Although it cited statistics for all general aviation flying, most of what happens at GBR is in a subset called noncommercial fixed wing flying. In 2020, the rate of accidents in that category was 5.29 per 100,000 hours, or 12 percent higher.

Also, since 2020, preliminary data shows an increase in non-commercial fixed-wing accidents from 891 in 2020 to 968 in 2022. Over the last 10 years, there have been an average of 977 accidents per year in this category of general aviation. While the long-term trend is encouraging, the last five years have seen relatively little improvement.

Given that about three-quarters of all general-aviation accidents happen during takeoff, approach, or landing, the accidents-by-flight-hours rates are useful but limited. That is in part because there is no actual count of flight hours; the FAA creates an annual estimate based on pilot surveys. That has long made it a less-than-ideal data element, not least because other transportation-related accident statistics use miles traveled as a standard metric of comparison.

Accident data used by AOPA and others for safety analyses is, by all accounts, incomplete. Among the reasons is that what qualifies as an “accident” is narrowly defined by FAA regulations. Those regulatory parameters require that an aircraft sustain “substantial damage” or that pilots or passengers suffer “death or serious injury” to be considered a countable accident. By excluding minor incidents and those that fall just short of regulatory definitions, the dataset undercounts at least some of the risk. Indeed, the 2014 AOPA report concluded that “accident statistics alone do not capture every event with safety implications.” AOPA also issues an annual report on accident trends and offers numerous programs focused on safety and training, with a focus on “improving pilot decision-making and proficiency.”

And while the NTSB performs detailed investigations of accidents to try to determine a cause, it can only recommend regulatory, equipment, or policy changes to the FAA. Critics argue that regulators are often slow to mandate those safety upgrades in both general-aviation aircraft and at the level of the airlines, particularly when the industry pushes back on the costs involved.

Nearby accidents, neighbors’ concerns, and relative risk

When I discussed flight instruction, safety, and general-aviation accidents with Sean Collins, AOPA’s eastern regional manager, like others, he pointed to primary flight training’s focus on safety. That is because, he acknowledged, mechanical failures are going to happen.

“With a mechanical anything, it’s going to break. Cars do it, trucks do it, planes are going to do it, too,” he told me during a January interview. “We take for granted [that] in our cars, we can just pull over on the side of the road. Obviously, [pilots] can’t do that,” Collins said. Pilot training, both primary and ongoing, includes preparing for all scenarios, he said. “It’s just a necessary component of what we do. Because at the end of the day, the pilot doesn’t want to get killed either,” he said.

As for the concerns of airport neighbors, he suggested that it’s a “natural misconception” to believe that incidents at GBR point to serious safety issues. “Like most things, it’s a perception. [Accidents] are relatively infrequent, so it’s a big deal when they happen,” he said.

The definition of “relatively” and “infrequent” is, based on years of testimony presented to the Selectboard, very much in the eye of the beholder. Some basic facts are available for interpretation: Since 1990, there have been 21 NTSB-investigated accidents connected to the airport, or an average of one every 19 months.

To neighbors’ concerns about increased activity near their homes, it’s true that general-aviation airplanes crash into houses and that those accidents happen in areas both rural and urban. Sometimes they injure or kill those on the ground, though most often fatalities are among those on board.

Some examples: Earlier this month, a Connecticut flight school’s Cessna clipped the roof of a home in Danbury and crashed into an adjacent shed between two houses. Last fall, a plane crashed into a multi-family home in Keene, N.H., killing both on board but with no injuries in the home. Another Cessna crashed into a home in Hermantown, Minn. in October. A child riding in an SUV was killed when the vehicle was struck by a plane in Broward County, Fla., amidst seven fatal crashes near an airport there over the last three years, including several into homes and some from a flight school.

A fatal crash with a Berkshire Aviation connection

In August, 2019, a twin-engine Cessna T303 Crusader lost engine power shortly after takeoff from Sky Acres Airport in Lagrangeville, N.Y. near Poughkeepsie and crashed less than a mile away into a house, bursting into flames and killing the pilot, a 61-year-old Woodmere, N.Y., attorney named Francisco Knipping-Diaz, and also a man inside the house, Gerard Bocker, also 61. Two of Bocker’s daughters were injured, including 21-year-old Hannah Bocker, who suffered severe burns over most of her body. The plane’s two passengers were injured but survived.

The NTSB’s final report determined the probable cause was a partial loss of power in both engines. Investigators looked at whether Knipping-Diaz performed adequate engine run-ups to address possible fuel-line vapor issues and noted a toxicology report that showed evidence of his previous cocaine use. But the NTSB concluded the crash was due to mechanical problems; the agency could not be more specific because of damage caused by the heat of the post-crash fire.

The pilot, plane, and accident have several connections to Great Barrington and BAE. In February 2018, Knipping-Diaz was preparing to take off from GBR in the same plane when he accidentally taxied off a snow-covered ramp at the end of the runway and into an airport neighbor’s field, damaging the airplane. Repairs, including reinstallation of the plane’s left engine after it was overhauled elsewhere, were completed at BAE’s maintenance shop, along with other maintenance on both engines and inspections later in 2018. But the plane’s final, pre-accident servicing and annual inspection, performed a month before the crash, was done at a different maintenance facility.

Today, BAE is among the defendants in wrongful-death and negligence lawsuits filed since 2021 on behalf of the Bocker family and the flight’s two passengers. As is common in aviation-related litigation, the list of defendants is long: The suits also name Cessna and its parent company, Textron Aviation; engine manufacturer Continental Motors; the estate of Knipping-Diaz; the operator of Sky Acres Airport; and several other aircraft-maintenance facilities.

The initial suit against BAE was filed in Berkshire Superior Court in August 2021. That case, and others filed in various jurisdictions, were largely consolidated into one now being heard in Dutchess County (N.Y.) Supreme Court. According to documents filed in the case, BAE is alleged to have returned the plane to service “with defects in its fuel system, engines, and turbocharging system” after it reinstalled the left engine and did subsequent maintenance and inspections. In its court filings, BAE has denied any responsibility.

When I spoke last December to one of the Bockers’ attorneys, Michael S. Miska of Philadelphia’s Wolk Law Firm, he declined to comment on the specific allegations beyond what’s described in court filings. He said the plaintiffs are continuing their examination of the plane’s engines and other wreckage. “Discovery is ongoing and our investigation is ongoing,” he said.

When I asked Rick Solan about the case in February, he pointed to the maintenance and annual inspection that were done elsewhere before the accident. “After he went off the runway here, we fixed the airplane and then signed it off,” he said. “And then he flew the airplane for a full year, year-and-a-half before the accident.”

According to the Cessna’s maintenance logbooks included in the NTSB’s investigation docket, in July 2018, BAE reinstalled the left engine after it was overhauled by Pine Mountain Aviation of Danbury, Conn. It also performed other maintenance on both engines and completed the aircraft’s FAA-mandated annual inspection. Three months later, in October 2018, it serviced the right engine, including replacing a cylinder assembly and turbocharger clamp. The subsequent maintenance and annual inspection were performed by SouthTec Aviation in Salisbury, N.C., in July, 2019, a month before the accident. SouthTec and Pine Mountain are also defendants in the case.

The case is being handled by a lawyer from BAE’s insurance company, Solan told me. In the end, he doesn’t think the crash was related to mechanical issues. “It was pilot error,” he said.

Accidents near homes in Great Barrington

In a rural area like south Berkshire County, when aircraft-engine failure happens at altitude, pilots have more time than non-aviators may realize to find an open field or appropriate “off-airport landing site.” As described earlier in this series, they’re trained via engine-out drills to quickly put the plane into the best glide angle and speed as they search for a place to land. But at low altitudes, particularly shortly after takeoff, options are much more limited. Both of last summer’s flight-school accidents were close to nearby homes, and both became emergencies at very low altitudes.

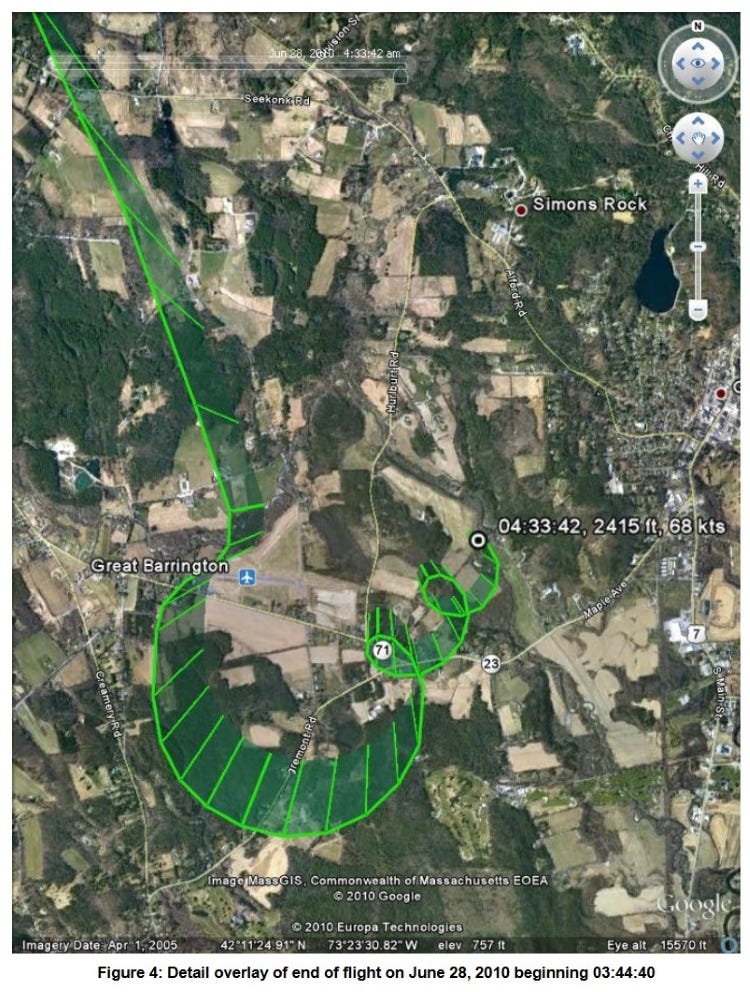

Over the last 30 years, the most serious accidents connected to the airport, including those that resulted in fatalities, occurred near the airport and close to houses. (Two fatal 1990 accidents are described in part six of this series.) In June 2010, a 20-year-old, instrument-rated local pilot with 550 hours of experience, and flying a BAE plane, crashed after losing his bearings while trying to land at GBR in heavy fog after midnight. The NTSB’s reconstruction of the flight’s final moments using its GPS data showed the plane was in a descending spiral over nearby homes while the pilot thought he was on final approach for landing. The pilot and his passenger were both injured.

The following summer, in July 2011, Rick Solan, who became one of four partner-owners of the airport after Koladza’s death in 2004 but was still an American Airlines pilot, took a passenger on a flight in a 1958 Piper J3 Cub owned by airport co-owner Jim Jacobs. He lost engine power shortly after takeoff when the plane was 150 feet above the ground. He navigated the plane between several nearby houses and crashed into a yard, coming to rest in some trees less than a mile from the airport off Route 71.

According to the final NTSB report on the accident, the engine’s failure was due to “improper engine storage preparation and improper return to service from indefinite storage,” which resulted in a stuck valve and low compression in two engine cylinders.

In his detailed statement to the NTSB, Solan described the second-by-second decisions he made to avoid crashing into houses, evidence of his training and long experience. Though in the section of the NTSB form where pilots are asked, “RECOMMENDATIONS (How could this accident have been prevented?),” Solan pointed only to trees at an adjacent property that limited his emergency landing options, rather than acknowledge the failure to follow the engine manufacturer’s recommended procedures for returning an unused aircraft to flight-ready condition. “If the trees at the end of the runway were cut, I would have been able to slip into the open area at the end of runway 29 and probably not put a scratch on the plane,” he wrote. Negotiations with airport neighbors about trees on their properties have sometimes been contentious, at least since 2008, when Solan and three partners formally took over the airport from Koladza’s estate.

That same BAE Piper Cub was involved in an August, 2017, crash in Salisbury, Conn., and it was also related to maintenance issues. During a flight lesson given by Archer, the engine lost all power as he and his student flew over a heavily wooded area. Archer ran through various engine-recovery procedures before putting the plane down in some treetops. Both he and his student escaped serious injury, the latter because he was wearing a lap belt, not the seat’s shoulder harness, which might have held him upright as the plane’s roof was partially crushed into the rear seat during the crash.

The NTSB investigation found the loss of power was the result of an improper crankshaft replacement during an engine overhaul four years earlier. Rick Solan told me that the FAA-certified mechanic who did the work was not a BAE employee, but he did engine overhauls for BAE at his home. “He took the engine physically to his house,” he said.

According to the NTSB’s final report, the agency concluded that the mechanic borrowed an outdated overhaul manual for the engine from BAE’s maintenance hangar; it didn’t include the manufacturer’s updated crankshaft-replacement instructions. As a result, a small dowel pin was not installed, leading to the eventual failure of the crankshaft gear in flight. Because it was an internal part, the error was not something BAE’s mechanics could have seen during subsequent maintenance and regular inspections, Solan said.

Archer has used that 2017 crash experience in his work with students and in presentations to other instructors. In a fascinating February 2020 podcast interview , he described that flight, his decision-making, and how training and experience came into play. He said his actions were “instinctual as far as how I did the things I had to do,” which included looking for a place to land that would not put others at risk. He said that “solid training right from the beginning” can help pilots overcome what he called the “startle response” during an emergency. “I’ve taken what I learned and apply it to all my students now,” he told the podcast hosts.

September’s crash was due to student error

Both of last summer’s accidents took place during flight school lessons: one in a BAE Piper Warrior trainer and the other in an aircraft owned by the student. The first, in the BAE plane, was on July 30: A student was taking off to the west, with Rick Solan instructing, when the engine lost power as they lifted off the runway. Solan quickly took control and opted to land the plane in a neighbor’s field immediately adjacent to the airport.

While the FAA noted the incident, because there was no damage to the aircraft or injuries, there was no follow-up investigation by the NTSB. Solan told me the engine had been running smoothly, was up to date on its maintenance and inspections, and had a long way to go before an engine overhaul at 2,000 hours of use. But moments after takeoff, an engine valve got stuck. He said there can be mechanical problems even in well-maintained airplanes and suggested an analogy: “You can come out of a doctor’s office after getting a perfect EKG, walk down the street and have a heart attack and die,” he said.

According to the 2014 AOPA study of instructional accidents, about a quarter of accidents during flight lessons result from a loss of engine power, which is comparable to the rate for all fixed-wing general-aviation accidents.

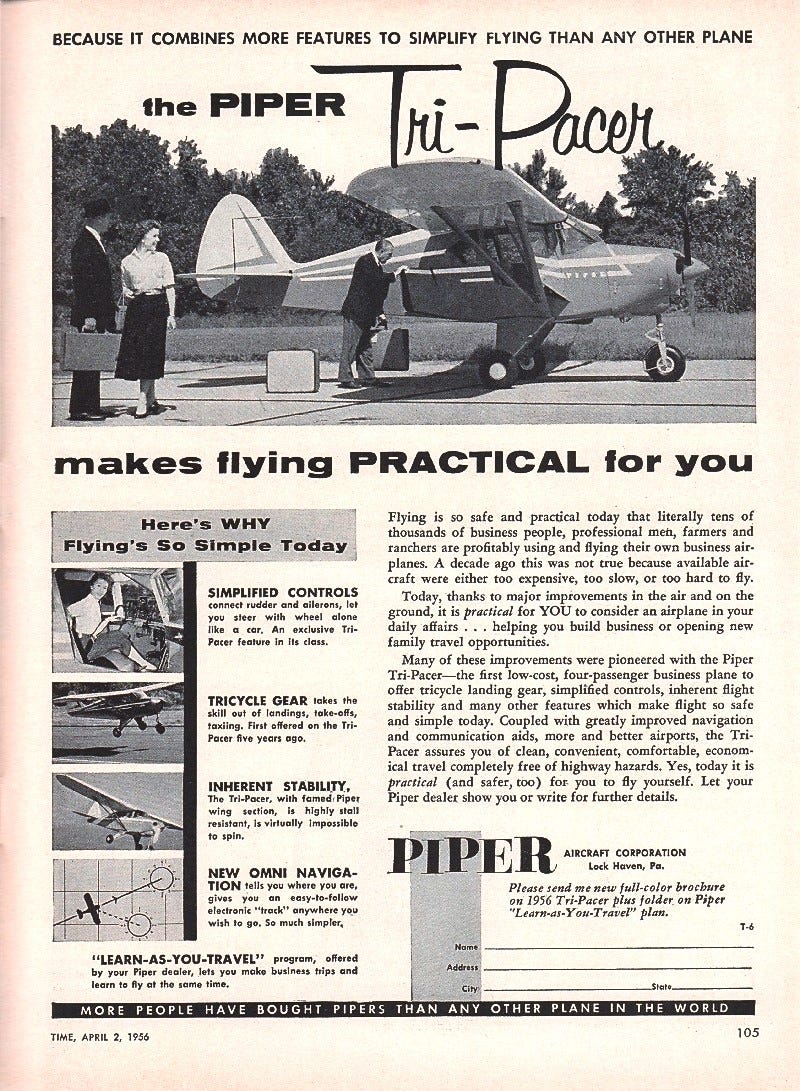

A more serious accident happened on September 18. Rick Solan was giving a lesson in a 1956 Piper Tri-Pacer owned by his student. After practicing takeoffs and landings at Columbia County Airport in Hudson, New York, they headed back to Great Barrington. As they were preparing to land from the west, Solan thought the student’s approach was too high and fast and called for a go-around. Just as the student applied full throttle, the engine died completely.

According to the NTSB’s preliminary accident report released in November, Solan immediately pumped the throttle to no effect. Because of low altitude, there was no time to troubleshoot, the report said. The plane crashed moments later into a cornfield just behind 146 Hurlburt Road. The plane’s left wing was severed, the fuselage crushed in several locations, and fuel was leaking from a breached fuel tank. Fortunately, both Solan and his student, a 57-year-old Connecticut man, were able to climb out safely. According to an initial FAA incident report, they suffered minor injuries; both men declined medical attention at the scene.

The NTSB report says the student “switched the fuel tanks” as they entered the airport’s traffic pattern. And an FAA inspector’s examination of the engine “did not reveal any mechanical irregularities that would preclude normal operation.” After abandoning the first approach for landing, the engine stopped with “no surging, no sputtering, it just quit,” according to statements taken by investigators. Had the engine stopped a few seconds later, the plane would have been past the cornfield and above houses on Hurlburt Road.

When I spoke to Solan about the accident a few months ago, he confirmed what that preliminary NTSB report suggests: As they were preparing to land, the student pilot mistakenly turned the Piper’s fuel-tank selector switch to “OFF” instead of changing the source of fuel from one tank to the other. With the tank selector in that position, there was no way to re-start the engine.

Solan told me that the location of the fuel-selector switch on the lower left wall of the cabin made it difficult to see from where he was seated, as the student’s legs blocked his view. “I take full responsibility for that,” he said, calling it “pilot error.”

In the eyes of regulators, as the instructor and pilot-in-command, Solan does bear responsibility for the mishap. At the time of the accident, he had more than 52,000 hours of flight time under his belt—a remarkable and almost unmatched amount of flight time that reflects his half-century of flying. (Solan is 67.) He told me that when the final NTSB report is issued, he doesn’t expect to be sanctioned, given that level of experience. Years ago, he said, they might have required him to go up with an FAA examiner for a check ride. But at this point in his career, he predicted a call with FAA safety officials to review the accident and discuss strategies to avoid a repeat occurrence. “They’ll talk to you for a couple of hours: What was going through your mind? How do you think you can handle it better in the future?” he said. “Bad things happen to good pilots all time.”

In response to questions about accidents during flight instruction, an FAA spokesperson told me that the agency’s goal is to help pilots comply with FAA flight-safety regulations. After this type of accident, they’ll “typically counsel the [instructor] and may require them to show they understand the regulations and how they’ll comply with them,” the spokesperson said. There are a range of sanctions the agency can impose, including fines and suspension or revocation of an instructor’s teaching certification. But that level of enforcement action is only for violations that are “repeat, willful and/or egregious,” the spokesperson said.

A Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for information about BAE’s flight instructors from the FAA’s Accident, Incident, and Enforcement database returned no records of any past sanctions. A separate FOIA request for information about the FAA’s certification of the airport’s maintenance operation found that, after its most recent annual inspection last August, the agency called only for improvements to how BAE updates a required quality-control manual. It also recommended installation of an emergency eye-wash station, given safety recommendations associated with the hazardous materials used there.

Since last September’s accident, the destroyed Tri-Pacer has remained up on blocks on the northern edge of the airport. That model of short-winged Piper went on sale in the early 1950s and was pitched as a low-cost, four-passenger airplane that anyone could fly. An advertisement in Time Magazine in 1956 said—perhaps with dangerous overstatement—that its tricycle landing gear “takes the skill out of landings, take-offs, taxiing.” The plane, the ad boasted, offered “clean, convenient, comfortable, economical travel completely free of highway hazards.”

During my frequent visits to the airport last fall and winter, the Tri-Pacer’s wreckage stood as a totem to the seriousness of the enterprise of general aviation. Gazing at the crumpled airplane, it’s hard not to think of the good fortune of Solan and his student to emerge from last year’s accident with only minor injuries—and to assume that over these many months, the damaged plane has served as a sober reminder, to those taxiing past, of the risks involved.

Indeed, in February, Rick Solan told me that while he’s been eager to disassemble the remains of the airplane and remove it from public view, it has served that purpose for him. “It’s a reminder to myself: Check the fuel. Check the fuel gauge,” he said.

The future of flight training at GBR

Airport neighbors might take some comfort from Jason Archer’s reputation far beyond this region as a committed teacher working to bring greater safety and better instruction to the general-aviation community—and also from Rick Solan’s long experience. Learning more about the specifics of flight training and the details of safety checks, aircraft maintenance requirements, and pilot certification could also help allay some fears—at least those rooted in the unknown. None of that will address other complaints about flight intensity, noise, and environmental concerns, of course. Nor will it mitigate any of the actual risks of an airport and flight school tucked into a residential neighborhood. But it could contribute to more understanding and a better-informed conversation.

Given the dearth of flight schools in the region, it’s likely that BAE’s will remain busy and continue to grow. The Selectboard’s recent vote may even create new pressure to attract more revenue-producing students. That’s because the board’s special-permit conditions cap the level of maintenance activity at the airport at the current level, limiting an important source of revenue.

In theory, the flight school will also be constrained by that maintenance cap: Increased usage of BAE’s training aircraft, or purchase of additional planes, will require additional maintenance activities. But it’s too early to know if, or how, town officials will effectively audit or enforce that maintenance limit, especially without specific, accurate information about current activities. As it relates to maintenance, the special-permit conditions only call for a summary of hazardous materials usage to be submitted to the town annually. (As of April 28, the final, voted-on language of the board’s special-permit findings and conditions had not been made public or filed with the town clerk. A court filing last week suggested it was still being reviewed by the town’s attorney.)

The airport’s plans for an upgraded administration building also point to continued expansion of its flight school: Drawings presented to the Planning Board in March 2022 show several more individual classrooms for ground-school training than exist today.

‘We’re all in this together’

When we met last year, just a few weeks after my own experience in the air, JetBlue pilot and former BAE instructor Hochstetter spoke thoughtfully and at length about what aviation has meant to him. “I’ve discovered stuff about my life on the ground from the air,” he told me, channeling Langewiesche. “We spend most of our lives with our nose to the grindstone, our head down working, paying bills, having relationships with spouses and other people—we’re living life,” Hochstetter said. “And we get wrapped up in our own worlds. And to look down, and recognize, that in every single one of those homes, somebody else has their nose to the grindstone, is living their life, with their own set of issues and problems. And that we’re all in this together.”

Indirectly and inadvertently, by widening the lens to include both pilots and those on the ground, Hochstetter framed the central question of Great Barrington’s long-running airport debate: How does the community weigh the airport’s risks and externalities against its benefits—the very criteria the town’s zoning bylaw requires be used to evaluate the special-permit application just approved? How the board’s evaluation of those criteria, and whether its conditions will prove effective—and stand up to scrutiny, legal and otherwise—remains to be seen.

∎ ∎ ∎

NEXT: In the final installment of eight-part THE AIRPORT series: The history of zoning in Great Barrington, a review of the recently completed airport special-permit process, and a look at what’s likely to happen next.