Lessons in truth, humor, and meeting the moment

∎ ∎ ∎

Thanks to a combination of memories faded by time, and, honestly, being slightly star-struck, I don’t remember everything about the afternoon and evening I spent with Tommy Smothers in the summer of 2004.

But the general feeling still lingers strong: Conversation that made clear his thoughtfulness, irreverence, and intensity-of-belief about the intersection of comedy, democracy, and the importance of speaking out. And, though I didn’t need reminding, that he was far from the bumbling naïf of stage and screen.

As war raged that summer in Iraq and Afghanistan, echoes of Vietnam-era antiwar activism—and his important role critiquing both that war and the ones then underway—were palpable and growing. So we talked about that, and money in politics, and the future of American democracy while sitting at a mostly empty casino bar late into the night.

Smothers, who died this week at 86, was half of the storied Smothers Brothers music-and-comedy duo whose late-1960s battles with CBS network censors over the content of their comedy-variety television show, “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” cemented their place in the political and cultural firmament.

Fresh-faced and clean-cut, Tom and Dick—his younger brother by a couple of years—were a popular nightclub act by the early 1960s, appearing on late-night shows like “The Garry Moore Show,” Jack Paar’s “The Tonight Show,” and in their own short-lived 1965 sitcom produced by future hit-maker Aaron Spelling.

As CBS looked for yet another program to sacrifice against NBC’s unstoppable “Bonanza” on Sunday nights, it gave Tom and Dick a shot. And the suits offered Tommy what passed for—back then, at least, in the era of three powerful broadcast networks and their lawyer-filled “standards and practices” departments—“full creative control” of the weekly show.

What could go wrong? With their short hair, red blazers, and thin ties, they were authentic army brats straight out of the Eisenhower 1950s who looked and sounded that way—while many in America were growing their hair long and trying to levitate the Pentagon. In that context, Tommy’s faux dopey-brother stage persona couldn’t have been less threatening.

What happened next has been recounted this week in countless obituaries and remembrances, but in brief: Anti-war jokes, sly references to drugs, and counter-culture-infused political satire quickly creeped into the groundbreaking show, meeting the late ‘60s moment and, for a time, enthralling younger television viewers who had never seen anything like it—dfdf

The show also featured musical acts including The Who and antiwar folk singer Pete Seeger, driving the CBS brass fairly mad and keeping their network censors busy—who, with rich irony, refused to allow broadcast of a first-season sketch that spoofed the censors.

And Tommy wasn’t shy about tweaking the network or the medium itself, once calling television “a lie” and “old and tired.” He later conceded that for a time, his edginess and oppositional stubbornness drained some of the humor from his work.

By today’s standards it’s hardly radical to address racism, politics, war, and guns on television. But at the time, seeing that in prime time, broadcast into millions of homes, was a surprise. The duo was ultimately fired for breach of contract in a they-got-Capone-on-taxes kind of way: They allegedly failed to deliver a tape of a show far enough in advance of airtime for the network to review. (A few years later, they won three quarters of a million dollars in a successful lawsuit against CBS.)

Tom and Dick’s help with “Will Markson for President”

What brought me into Tom and Dick’s orbit on that day in June, 2004, was the presidential “campaign” of one their writers, the comedian Pat Paulsen, launched on the show in 1968. It started as a series of on-air editorials about issues of the day but soon became a full-fledged “Paulsen for President” spoof that satirized the language and absurd conventions of modern politics. (One of Paulsen’s slogans: “Just the common, ordinary savior of America’s destiny.”) Also tame by today’s standards, it was still novel and irreverent.

Inspired by that bit of history, in 2003 I launched a similar mock campaign that aimed to marry absurdist comedy to a nonpartisan movement for democracy reform. In the guise of an out-of-nowhere candidate named Will Markson—“America’s Favorite Fictional Candidate for President”—I traveled the country for most of two years giving offbeat speeches and advancing ideas to increase voter participation. “I’m running to win,” my alter-ego Markson insisted, “but if not to win, then I’m running for president to not lose too badly.”

As a project to improve American democracy and increase citizen engagement, it was squarely in Tommy Smothers’ wheelhouse. So when I learned that Tom and Dick would be at the nearby Mohegan Sun casino, in southeastern Connecticut, for a week of performances, I reached out. To my surprise, it took only a couple of emails for them to agree to meet and film an “endorsement” of my comedic, pro-democracy candidate.

Without much of a plan, we met in their dressing room and started rolling tape. I recently found a copy of that 2004 video clip; it’s easy to see that I was nervous as hell. But Tom and Dick carried me along. Watching it today, their ease and interplay, honed by half a century of work together, is evident in how they react to each other and move an unscripted bit along to a satisfying conclusion. (This week, Dick said of the “devastating” impact of losing his older brother, “Every breath I’ve taken, my brother’s been around.”)

The Smothers Brothers endorse "Will Markson" for president in 2004.

The video was posted to the Markson for President website, some of which still lives on thanks to the Internet Archive. It likely wasn’t widely seen: YouTube didn’t launch until the following year, and it was hard to get streaming video in front of a wide audience without breaking the bank.

After filming, I stuck around the casino for dinner and watched their show. The performance offered a few gentle political barbs but was mostly a fun bit of nostalgia for longtime fans. The audience roared at familiar sketches, from Tommy’s Yo-Yo Man to his well-known refrain, “Mom always liked you best!” His performances in those days often included a line delivered half as a joke, but clearly meant as something more. “Truth,” he’d say, “is what you can get other people to believe.” As we tumble into the 2024 campaign, that hits like a prescient warning.

Afterwards, Tommy and I met for drinks and talked far longer than I hoped or expected. In the couple of decades since, I’ve often thought about that encounter, and, more broadly, the historical lessons from Tom and Dick’s experience.

Their show was canceled in April, 1969. Two months later, its writers, including a young Steve Martin, Rob Reiner, Mason Williams, and Bob “Super Dave Osborne” Einstein, won a prime-time Emmy Award for their writing on the show. And in what today seems a historically relevant footnote, what immediately filled their time slot was “Hee Haw,” the country-music-based variety-and-comedy show that was the mirror opposite of the Smothers’ edgy-for-prime-time political satire. But it was, importantly for CBS, far more palatable to the rural and Southern network affiliates fielding complaints about the radical Smothers boys just as Richard Nixon was settling into the White House. (Tommy was convinced Nixon himself was involved in the show’s cancellation.)

“Truth is what you can get other people to believe.”

—Tommy Smothers

Looking back, perhaps the pivot to “Hee Haw” marked the first stirrings of the profound cultural zigzag to come: From broad calls for radical change in the 1960s to, in their place, a less threatening and nostalgic look backward that would eventually help to elect Ronald Reagan.

Tom and Dick continued to tour—including shows last year—reportedly performing more than 100 shows in some years and making numerous television appearances. In a 2005 interview, Tommy described his first discovery during the battle with CBS. “I didn’t even know I was saying anything important until they said, ‘You better stop.’” And while his politics were far left, he wasn’t necessarily partisan or close-minded. “When you look at stuff and kind of criticize things that don’t make sense,” he said in that same interview, “it doesn’t matter what side it comes from—left or right.”

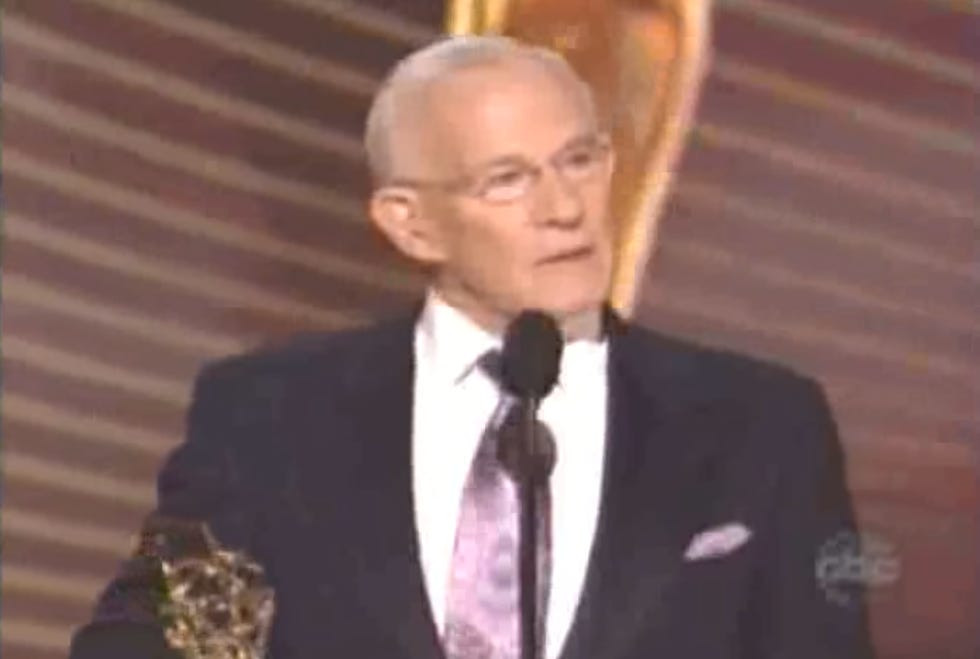

In 2008, Tommy was awarded a belated Emmy for his work on “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.” Introduced by Steve Martin, he was cheered with a standing ovation; in the audience, Dick was smiling ear-to-ear.

After thanking his writers for “getting me fired,” he said, “It’s hard for me to stay silent when I keep hearing that peace is only attainable through war,” a nod to ongoing violence in Iraq and Afghanistan. He then dedicated his Emmy to those “who feel compelled to speak out and are not afraid to speak to power and won’t shut up and refuse to be silenced.”

In memory of Tommy Smothers, that bears repeating: Speak out, refuse to be silenced, speak truth to power. For comedians, journalists, and everyone else, that’s a credo worth embracing.

∎ ∎ ∎