Now ninety years old, Ralph Nader discusses his American Museum of Tort Law, the power of organized citizens to make a difference, and lessons he learned growing up in a small, working-class town a stone’s throw from the Berkshires.

∎ ∎ ∎

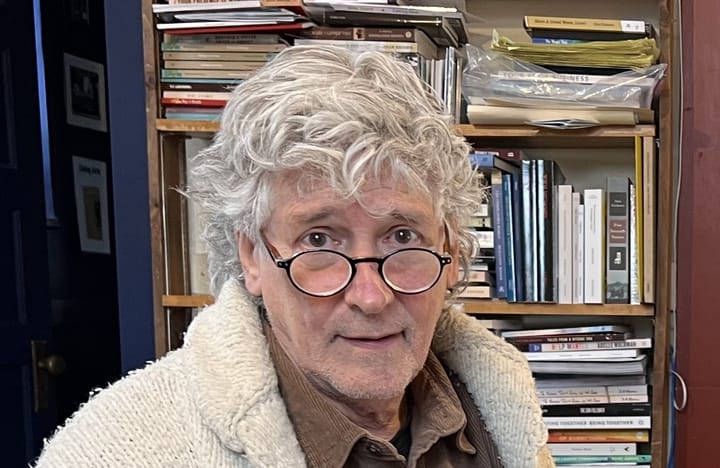

Earlier this year, the consumer advocate, public-interest lawyer, and (still controversial) former presidential candidate Ralph Nader turned ninety years old.

In this Berkshire Argus Podcast conversation, we discuss the American Museum of Tort Law that he established in his hometown of Winsted, Connecticut, his advocacy for democratic rights like jury trials, and his belief in the ability of citizens to organize and influence their government.

This episode accompanies an Argus profile of the Tort Museum, “The Unlikeliest Museum.”

TRANSCRIPT: A Conversation with Ralph Nader (2024)

Bill Shein: For nearly a decade, many of us in South Berkshire County have driven through Winsted Connecticut, perhaps on our way to the airport in Hartford, and seen a sign for the American Museum of Tort Law, a name that some may think, is the most unusual combination of words in the English language. Many don’t know the term tort law, which is the law of wrongful acts, and a museum dedicated to it may seem even more bizarre.

It’s unlikely that on a lazy summer day, your kids are clamoring for a visit to any museum, much less one devoted to the legal system. Never mind that tort law is fundamental to our individual rights under the Constitution—quaint as that may sound in this fraught moment for American democracy.

The museum was the brainchild of consumer advocate and activist Ralph Nader, who grew up in Winsted, a working-class community a short drive from the Berkshires. Nader turned ninety years old this year. And while working on a Berkshire Argus story about the museum, I interviewed him to discuss his career and the museum, which opened in 2015. After years of planning and fundraising, it grew out of Nader’s decades of work dating to the mid-1960s, when he and his teams of young lawyers and activists successfully advanced new laws and the creation of federal agencies focused on auto safety, workplace safety, and things we take for granted today, including the Freedom of Information Act, Clean Water Act, Consumer Product Safety Act, strong protections for whistleblowers, and much more.

What struck me most about our conversation was not only Nader’s undiminished fire for justice and fairness, but something that may not be immediately apparent, especially to those only familiar with his runs for president. And that’s Nader’s essential conservatism: From the small-town, working-class values he learned while serving customers at his father’s restaurant in the 1940s to his unshakeable belief in the Constitution and the structures of American law and democracy, particularly a system that relies on a jury of one’s peers to fairly evaluate allegations both criminal and civil.

He also maintains a remarkable faith in the ability of citizens to organize and influence the United States Congress, even as that body has been overwhelmed by cash from corporate America and wealthy citizens. As you’ll hear, Nader’s insistence that a few hundred citizens can summon a member of Congress and then send them back to DC with clear demands for action may sound quaint—almost naive given today’s political realities. But what it may actually reflect is how far our democratic systems have strayed from what they should be. A cynical reaction to Nader’s clamor for old-fashioned citizen organizing and collective action may be the best evidence that things are not working as they should. And as he says during the interview, the worse Congress gets, the more citizens withdraw. A perverse incentive, he says, that leaves masses of people giving up on any hope for truly responsive government, leaving politicians to carry on without concern.

In this podcast conversation, Ralph Nader and I spoke about tort law, his career, the museum and Winsted and the time we crossed paths nearly twenty-five years ago in a way that I think illuminates his commitment to the kind of engaged citizenry he believes we need more than ever. Our conversation runs about a half hour.

Bill Shein: I’d like to start with something you said in a book that you wrote in 2007 called, “The Seventeen Traditions: Lessons from an American Childhood,” which was about your life growing up in in Winsted and things you learned from your parents and others. You wrote, “There is great joy in pursuing justice, and that joy should be available to everyone.” And I want to ask you to talk a little bit about that, and what that means.

Ralph Nader: Well, you know, people go through life looking for gratification, and some of it is good food, some of it is recreation. But the most important is whether we live in a just society that minimizes pain, deprivation, disrespect, denial of opportunity, and various injuries and illnesses that are preventable. So that’s why I realized, at a young age, that the pursuit of justice also was received with gratification. Not necessarily the beneficiaries, but the pursuer of justice. It’s a good way to live.

Bill Shein: And how has that been for you? I have a question further down on my list about the experience that you had after “Unsafe at Any Speed” [Nader’s 1965 book about auto safety] was published, and you ended up in litigation with General Motors for standing up for safer cars. I was interested to know how that lawsuit shaped your thinking about this work as you proceeded in your career?

Ralph Nader: Well, when “Unsafe at Any Speed,” the book, came out in November,1965, GM called up the publisher and said, “We just heard about this book. We’d like to order a dozen copies, will you take a check?” And my publisher said, “Take a check from General Motors. Yeah, I guess it’s not going to bounce.” In the meantime, what they didn’t tell us was in the prior several months earlier, it hired a private detective to try to get dirt on me and to follow me around the country. That was done to their other critics, because a lot of the people working in this area for GM and Ford were former FBI agents who went into the private or corporate sector after leaving the government. So that’s the way they responded. Only this time, they followed me up to Congress and were caught by a guard.

And the uproar resulted in a widely covered congressional hearing by Senator Ribicoff of Connecticut, who was chair of a subcommittee [of the Committee on Government Operations], and the result was, within a few months, the passage of the first regulation of the auto industry, safety, pollution control, fuel efficiency. Within a few months, Lyndon Johnson invited me to White House gave me a pen at a signing ceremony in September, 1966. So you can see how fast Congress moved in those days compared to the gridlock and sluggishness and cowardliness of today.

Bill Shein: You mentioned Connecticut, and the American Museum of Tort Law is located in your hometown of Winsted, Connecticut. And I wanted to ask you first of all, for those who really aren’t familiar with the terminology, what is tort law and why is it important?

Ralph Nader: Well, tort law, the word comes from the French, which means harm, an injury, and millions of people are wrongfully injured in his country every year. You know, on the street, a lot of crimes are torts, somebody gets attacked on the street or assaulted. Also, defective cars lead to serious collisions, unsafe drugs, pharmaceuticals, flammable fabrics, toxic pollution leading to respiratory ailments, a whole assortment of dangerous products, including toys I might add.

All of those come under the rubric of the law of wrongful injury, which is tort law. Because under tort law, if someone wrongfully injures you, you can sue them, get a contingent fee lawyer and get a trial—if you don’t want to settle—and make the perpetrator pay your damages, whatever wage loss, medical expense, disability, and there’s no such museum in the world until the American Museum of Tort Law was established in 2015.

And it was established to public educate people. And after a few years, it went virtual. And now it can be seen and people can take a tour of the exhibits, takes at least an hour and become informed about what their rights and remedies are, if they are wrongfully injured. Not just to get compensation, but for two other purposes: To disclose, publicly, defective information or information about harmful products and processes so the general public knows what’s going on and can take precautions. And second, telling other companies, for example, or other potential wrongdoers, this is what you may have to be held accountable for. So, anybody from Singapore to Stockholm can take a free virtual tour of the American Museum of Tort Law. And the website is tortmuseum.org.

Bill Shein: And how did the idea for museum come to you?

Ralph Nader: It wasn’t difficult! Why wouldn’t it come to me the minute I was in law school? You talk to people and nobody would know what tort law is. Even the newspapers—there are all kinds of examples where they report lawsuits, but they don’t attribute it to tort law. Where, if they report a civil rights discrimination suit, they will say, “civil rights laws.” But the media, for some bizarre reason, refuses to say that when Trump assaulted women, he committed a tort under tort law, and he was sued under defamation, which is part of tort law, or somebody crashed into a tree because of a defective throttle built by an auto company and sued the auto company under tort law. No, they just say they sued the auto company for damages. If you can figure out how to turn them around on this, I’d be the first to listen to you.

Bill Shein: And why do you think they don’t include that? Are they just not well-schooled in law?

Ralph Nader: Well, they certainly use it when they report the insurance companies’ push for tort reform. How many times have you heard that, right? Well, I have no idea. What one reporter told me is it’s because nobody knows what tort law is. What is tort reform?

Bill Shein: And I’ve heard you call tort reform “tort deform.”

Ralph Nader: Right, because it takes away rights that people already have under the American system of civil justice, and the tort law that animates it. The word “reform” usually refers to expansion of people’s rights. So, it’s a misuse of the word by the insurance company lobby, and I don’t want them to get away with that.

Bill Shein: So what’s their focus today?

Ralph Nader: Well, their focus today is to reap the profits from their destructive use of indentured state lawmakers in state after state—not all of them, but including Connecticut—to weaken the law of torts. And to, by absentee dictate, decide what judges and juries individually and uniquely listen to the evidence in specific cases. So it’s like absentee control of the courts by legislators who are in the pay—campaign cash—of the corporate wrongdoers, lobbyists, [who] don’t want to be held accountable.

Bill Shein: The cases that were chosen to be featured in the museum: How did you decide which ones would become exhibits?

Ralph Nader: Well, there are two categories: One, cases that made a difference and broke new ground. So cases that provided new remedies. You know, the law of torts “has to be stable, but it cannot stand still,” in the famous words of Dean Roscoe Pound of Harvard Law School many years ago. And, so, there are cases that broke new ground. They allowed, for example, compensation for pain and suffering, or new forms of evidence to be introduced. And then there are the cases that didn’t break ground, but they’re so significant that we put them in the museum. So we have the asbestos litigation, the tobacco litigation, the Pinto’s vulnerable fuel-tank-fire litigation, we have the privacy litigation with my case against General Motors, and there’s a full size 1963 Corvair right in the museum.

And then there are other cases. For example, there used to be a doctrine, if a company was negligent in harming somebody, the company in court could say, well, all the companies do the same thing, all the companies have the same product. And along came a judge who said that’s no excuse: Tugboats should have radios, and the fact that the industry did not have radios did not exonerate the tugboat that didn’t have a radio and couldn’t alert and save the occupants in a terrible storm at sea.

Bill Shein: So let’s talk a little bit about why you decided to situate the museum in Winsted compared to Washington, D.C. or somewhere else.

Ralph Nader: Well, because I believe in supporting the hometown, number one. Number two, why should everything be in big cities? We have to decentralize. The Baseball Hall of Fame is in Cooperstown, New York, and that’s a small town. The Football Hall of Fame is in Canton, Ohio, that’s not a large town. And also, it’s very, very much more expensive—it would have been ten times more expensive if had it installed in Washington, D.C.

Bill Shein: And I noted when I was there that the museum is in a building that was formerly a community bank, and that it’s between a law firm on one side and a church on the other. It sort of struck me as a certain kind of symbolism: I wonder if it’s fair to say that there’s something religious about your fervor for using the law to fight for justice and fairness?

Ralph Nader: Well, maybe the golden rule, that applies to tort law, doesn’t it? So when someone wrongfully injures you, that person is violating the golden rule. But it was purely coincidence. The bank, by the way, when it was a bank, we were in elementary school and the teacher would walk us down to the bank, the whole class, and open savings accounts. We put a dime in the savings account to teach us savings habits. How quaint.

Bill Shein: How long did you keep your account there?

Ralph Nader: Oh, for quite a few years, actually. Yeah.

Bill Shein: And I understand that your father’s restaurant was not too far from there, right?

Ralph Nader: Yeah, it was just three blocks down, right in the middle of Main Street, opposite what used to be called the New England Knitting Mill on the other side of Mad River, which had about four hundred workers at the time. And they would come for lunch or for coffee, and I would be behind the counter. And I would always have a very informative conversation with them. They taught me a lot.

Bill Shein: Yeah, I read in your book about growing up there that having those conversations, with all different kinds of people, was formative for you?

Ralph Nader: Very formative. People, you know, are rather candid, forthright, honest, when you’re having a bite to eat, and they’re making small talk, and I would talk to them, and I remember at the time that they would come in—a lot of people smoke, there was always smoke in a restaurant. And we’ve come a long way with no-smoking arenas. And when I was growing up, almost fifty percent of adults smoked, and now it’s under fifteen percent. So this is progress.

Bill Shein: Let me ask you about one of the exhibits. When people think about tort reform, and you know, the exhibit about the McDonald’s hot coffee case. Something very interesting happened as I was driving to the museum, that morning that I went to visit it. There was a local radio commentator talking about the $450 million judgment against Trump in New York State. And this commentator compared it to the McDonald’s hot coffee case and said that both of them were cases that eroded people’s confidence in the judicial system because they were outsized awards. And then went on to present this caricature of the McDonald’s case. And the true facts of that case are not well known. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that case, and why it’s one of the ones presented in the museum and why it’s proven so hard to correct the public’s perception of that case, and so many people still see it as frivolous?

Ralph Nader: Well, the distortion of that case did a lot of damage. In state legislatures when the insurance lobby and other corporations wanted to weaken people’s rights to hold them accountable for injuries that were wrongful. They would trot out this case, “See how crazy, system’s out of control, frivolous case, out-of-control juries, ambulance-chasing lawyers.” And of course, it was a conservative jury and a conservative judge in a southwestern state that decided it. And when they first saw the description of the case, they all thought, “Oh, this is really off the wall.” And then they start listening to the evidence. And the evidence is McDonald’s, in order to keep the coffee much hotter than its competition, raised it to a level far, far hotter than the coffee you make in your kitchen. And so for commercial purposes, they reduced the burn time to just three or four seconds instead of say twelve or fifteen seconds on the skin. And when the jury and the judge heard all that, well, they changed their minds and they provided an adequate award, which was then settled for a lower figure.

But she offered to settle before she filed the suit just for the cost of her medical care, when a coffee spilled onto her body, and they wouldn’t even settle, even though there had been thousands of complaints against McDonald’s in prior years about scalding coffee, without warning you on the cup, you know. You get a hot cup of coffee, your frame of reference is the coffee you brew at home, you’re not ready for scalding coffee.

So this is a museum that changes people’s minds. You know how hard it is to change people’s minds? They come in with propaganda from Aetna and other insurance companies about frivolous lawsuits, and by the time they go through all the exhibits, they’ve had an education. And the way the exhibits are, they respect people’s intelligence, they asked them, “How would they decide the case, if the facts were changed this way or that way?” And by the time they come out, they understand the reality and not the propaganda and distortion. And they feel equipped, should they be wrongfully injured, to assert their rights. There’s huge underutilization of tort law: Over ninety-five percent of wrongfully injured people who would have an action under tort law never get to a lawyer. And the purpose of the Tort Museum is to give people a sense that they have rights that they weren’t aware of, and if they pursue them—to not only get compensatory justice, but they’ll generate deterrence for a greater safe society, and more disclosure, so that regulators and legislators can establish mandatory safety standards across the board, product by product, and not have to wait for another lawsuit.

Bill Shein: You mentioned that one of the things that comes out of these cases through discovery is a lot of information. It forces companies to disclose things. And I read in something else that you wrote about the influence of the muckrakers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that you read about when you were young. And when you began your career in Washington, it was at the height of the work of folks like I.F. Stone—and you wrote a tribute to Stone that I’m going to quote here, if I can. You wrote, “Notwithstanding poor eyesight and bad ears, he managed to see more and hear more than other journalists because he was curious and fresh with the capacity for both discovery and outrage every new day.”

So I’m wondering what you would say to folks who feel beaten down by or exhausted by these fights for justice and can’t seem to muster the energy or outrage that you seem to still have after all of these years of engaging in this?

Ralph Nader: Well, I would urge them to read my book, “Breaking Through Power: It’s Easier than We Think,” a little paperback, shows how one or two or three people have made the difference. Most of the great blessings we inherit from our history in our country were started with a conversation between two people, four people, six, eight, a social movement starts, politicians take heed. So they shouldn’t get discouraged.

And besides, nobody’s smart enough to be a pessimist. According to Norman Cousins, pessimism has no function. Other than to increase the purchase of Valium or some other nostrum. It doesn’t make you feel good. It makes you feel powerless, insignificant, that you don’t count. So fighting the good fight is open to all citizens and you know, you’re going to lose a lot. On the other hand, you’re going to find new friends, you’re going to influence more people, even if you lose the battle. And as Eugene Debs, a great labor leader in the early twentieth century used to say, fighting for justice for workers, “You have to learn how to lose, lose, lose—until you win.”

Bill Shein: You’ve advocated for a strategy of trying to mobilize one percent of everyone in each congressional district as an organizing strategy.

Ralph Nader: Oh, yeah, it often doesn’t take more than one percent Take any issue, Bill, and say it has to go through Congress to get it resolved [or] reformed. Okay. So you say, well, what does it take in a congressional district? Well, you know, we got the auto companies regulated with less than a thousand people. Why? Number one, people understood what safer cars meant for their families and children. It wasn’t some esoteric provision in the corporate tax code. Number two, the people who were advocating knew what they were talking about. They weren’t caught by corporate reviewers with mistakes and discredited. Number three, they represented public opinion, they represented a majority of the people. And with that they focused on Congress, which is the chief decision-maker at the time instead of one legislature at a time.

Now, any other issue? If you have one percent, that’s two and a half million adults, active in four hundred and thirty-five congressional districts, that’s overwhelming. You have people who make that a civic hobby. Let’s say they spent five or the hours, average, a week on it, which is what people often spend on a hobby. You have that number, and let’s say you want to audit the gigantic, wasteful, bloated military budget, which has been run by the Pentagon, in violation of a 1992 federal statute requiring all departments and agencies to provide annual audited budgets to the Congress, you know, common sense. Congress is the appropriator funds. And every secretary of defense admits it, says they’re going to get it underway. It’ll take five years. That’s what a mess it is.

But by then there’s a new secretary of defense. And now what would it take to do that up against the Lockheed Martins and the Raytheons and United Technologies and others who would like an unaudited budget so they can squirm their way to even greater profits? Well, if you had two and a half million people working on that, and you know, it’s over half of the federal government’s operating budget, taking a lot of money from communities, and public works, better schools and mass-transit bridges, and so forth, it would be a slam dunk, because the majority of the people would be behind you. And you would have the facts, and you would focus on five hundred and thirty-five people. That’s all, five hundred and thirty five, to which you have delegated your constitutional authority, and to which a majority now are turning against you, on behalf of about fifteen hundred corporate paymasters.

Bill Shein: What do you think about that the challenge today that some people see when it comes to influencing Congress—four hundred and thirty-five single-member, winner-take-all districts, gerrymandered and uncompetitive? What’s your take on the strategy needed in that environment? And is there hope for any democracy reforms that could make a difference alongside the kind of activism you’re talking about?

Ralph Nader: The methodologies all key here, Bill. First of all, you’ve got to have a different mindset as a citizen when you confront members of Congress, instead of being awed or sycophantic. You say, “You guys work for us. We’re paying your salary. And you’re selling the US government at bargain prices, to special interests, who work against our interests as families, conservative liberal, like, who wants the same things for their children back home, where they live, work, and raise, raise their kids.”

First, attitude, is that once you have that attitude, you formally summon your senators and representatives to town meetings that you have arranged for and that are devoted to your agenda, not their agenda. And you basically say, you know, we have five hundred people, clearly on a petition here, they put their names legibly, put their occupations down, their email, serious people, give us a convenient time. And we want to summon you to a town meeting in the local high school auditorium or some other public venue, and you will listen to us, we will present our demands, we will listen to your response. And then we expect to send you back to Washington with your instructions. Because you work for a government to supposedly of the people, by the people and for the people, not of the corporations, by the corporations, and for the corporations.

That is a dynamic that has to be initiated, turning around the choreographed manipulation of town meetings, by the flacks for senators and representatives, where they make you discuss what they want to hear, not what you want to have them listen to.

Now is that hard to do? Absolutely not! People will do so much more difficult things in their daily lives like raising their children, trying to get enough money to pay their bills. Being an active citizen is light work, compared to what people go through: Injuries, sicknesses, loss of livelihood, and so on.

So people have to wake up and view themselves with greater significance, they’re going to have a higher estimate their own significance, because the more these politicians run by corporate lobbyists reduce their expectations of Congress, the more that citizenry gives up getting angry and roaring back, saying, “Hey, you took away our rights, you took away our representatives in the public interest,” they get more cynical and withdraw. So it’s a sort of perverse incentive that the worse Congress gets, the more the citizenry withdraws, they give up on themselves. That’s how democracies fail: To have masses of people give up on themselves.

Bill Shein: On that idea of the Tort Museum as a place to be educated and inform the folks that you’re talking about who could then become more active: What’s next for the tort Museum? What would you like to see happen?

Ralph Nader: Oh, I’d settle for more visitors. We have a very apathetic public in the United States of America. It’s very prone to entertainment, sports, concerts, they show up. But in civic arenas, it’s like pulling teeth. So you basically have a ten-mile perimeter around Winsted, a population of, let’s say, a twenty-five, twenty-six mile perimeter. You have maybe 100,000 people at least, you have Waterford, Hartford, Torrington, and it’s almost impossible to get these people to take a Saturday or Sunday afternoon off with their children and come and view something in their own defensive interests.

The Museum of Tort Law is very easily viewed, as you know. Has great artwork, clear, you can stand there, nobody’s rushing you, there’s no docent. You teach yourself, you learn a lot. And it’s very, very difficult to get people to come. In the old days before television, they would line up for a block and a half. But they have too many ways to distract themselves, iPhone in their hand to begin with, immersed into the internet Gulag. And they haven’t taken advantage of it.

So we want to make an offer to those people who read the Berkshire Argus: All they have to do is go to the museum and we’ll give you two-for-one admission. We’ll admit two people for the price of one. And all you have to do—the staff will take it on faith—is say, “I read about the Tort Museum in the Berkshire Argus. And I have a friend with me or child or parent, can we get in two to one?” Absolutely.

Bill Shein: Great. So I’d like to end with something about the importance of the Museum of Tort Law and the emphasis on the power of the courts to provide accountability through a jury of one’s peers. And I want to tell a quick story about how you and I almost met, back when I used to live in D.C., that was in December of 2000. It was just a couple of days after the Bush v. Gore decision, and you were facing an onslaught of criticism, in the middle of the storm there.

And on that day, in mid-December of 2000, I was in a large room at the D.C. courthouse because I had been called for jury duty. And you were sitting just a couple of seats away from me. And I didn’t know you were there until they started calling people’s names for jury pools. And I was wondering if you remember that day at all? Because I thought, at the time, you know, here’s Ralph Nader in the eye of the storm, having just finished a presidential campaign, and here he is appearing for jury duty like every other citizen. And I wonder if you remember that day, if you were called to serve on a jury, what the case was, and anything else you remember about that day.

Ralph Nader: Yeah, I remember because I always tried to get to serve on a jury. When I was a lawyer, in Connecticut lawyers were not allowed to serve on juries. They were deemed to be too influential for the rest of the jurors. But in D.C., lawyers can serve on juries. But every time I honestly answered all the questions, one of the lawyers would dismiss me.

So I never got to serve on a jury in DC. And I remember it very well because so many people in the District who received jury notices just throw them away. And so I was called about every three years because the jury pool was shrunken, and the institution there didn’t have the staff to go after the people who threw a jury notice away. So there were a small number of people kept being asked.

And I remember very clearly standing in line, and you’d sit, you get a five minute video on jury trials and the Constitution. And then you’d go to be interviewed. So you were there.

Bill Shein: I was there! Yeah, I remembered I was a row or two, I think, it’s two rows behind you. And it looked like you were there with an aide and you had piles of paper and seemed to be hard at work. I noticed that before they called your name. And then when they started reading out names, off you went to a jury pool. And to not get selected. I also did not end up on a on a jury that day. But I remember that and I’ve told that story many times.

So is there anything else that we haven’t touched on, Ralph, that you want to tell me about? About the museum or anything else?

Ralph Nader: Yeah, the one thing I say to people, is what my father once said to me, “If you don’t use your rights, you’re going to lose them.” Why? Because when you use them, you exercise their muscle. You let people know about those rights, you get a commitment. You get justice as your award very often. And people have not appreciated the laws of civil justice, trial by jury. And predictably, the number of jury trials is plummeting toward extinction. The judges are pressuring litigants to settle before the trial. That way they don’t have to work and preside over a trial. And there’s no demand to serve on juries.

This is one of the great democratic institutions in the history of the world, the American jury system, where people, ordinary people can judge the most powerful corporate defendants who’ve done a lot of wrongdoing: Opioids, oil spills, tobacco, cancer, asbestos. And it should be a pleasure, a privilege to serve on a jury. And they take every opportunity to make an excuse so they don’t have to serve on a jury.

So I tell people, you’re undercutting the democratic institution that can protect and defend you, your family and your descendants. So always heed the invitation, or the call for jury duty, with pleasure and enthusiasm. The interesting thing is a lot of people who are called for jury duty go in grumbling, but they come out at the end of the case tremendously encouraged and pleased with the institution and respected accorded them.

Bill Shein: Ralph, I really enjoyed having a chance to talk to you and I hope we get to connect again sometime.

Ralph Nader: Okay, thank you.

Bill Shein: That was Ralph Nader, the lawyer, activist, consumer advocate, and founder of the American Museum of Tort Law in Winsted, Connecticut.

Now, while The Argus does not accept advertising or sponsorships, we’re not going to decline Nader’s offer to Argus readers and listeners: Mention the Argus to receive a two-for-the-price-of-one deal at the Tort Museum through July 1 2024.

You can read our story about the Tort Museum at berkshireargus.com.

This is Bill Shein and thanks for listening to the Berkshire Argus podcast.

∎ ∎ ∎