Long-sought parking and lake access for Egremont residents are both connected to an agreement for dam-repair funds. Whether—and how—that will work, and what it will mean in practice, is complicated.

(This is the second of two parts. Read part one.)

∎ ∎ ∎

When I first called George McGurn, the chair of the Egremont Select Board, to discuss the condition of the dam on Prospect Lake, it was early on a rainy morning in mid-August—one of many such mornings during a spring and summer of frequent precipitation. “You know, when it rains all night, it makes me nervous,” he said.

A couple of weeks earlier, McGurn told the Select Board that heavy rains this year—he called one storm “a deluge”—had caused more damage to the essential-but-long-ailing dam that keeps the lake several feet higher than it would be otherwise.

Maintaining that water level is why a safe, fully functional dam is vital—and valuable—for owners of the 40-odd homes around and near the lake, and for others who have long enjoyed this Massachusetts “Great Pond” for swimming, boating, and year-round fishing. And, of course, the dam’s health is important to those who would be in the path of floodwaters should it fail.

McGurn, who was first elected in 2017, clearly enjoys talking about infrastructure. During that first hour-long conversation, we also discussed other dams in Egremont and the state-funded, eight-million-dollar, road-and-sidewalk project wrapping up in South Egremont—the small town’s modest commercial hub.

Perhaps he’s fond of the topic, he said, because he’s been around infrastructure since childhood: McGurn’s father, also named George McGurn, was an Illinois attorney with clients involved in transportation and construction. Prior to starting his own firm in the nineteen sixties, the elder McGurn also played a key role in establishing the first toll highways built around Chicago as an assistant attorney general and chief counsel for the Illinois Toll Highway Commission. And McGurn the younger’s long career in management, university administration, and international economic development included work on infrastructure projects in the former Soviet Union and elsewhere, he told me.

Concerns about a privately owned dam

Central to any conversation about Prospect Lake Dam is that it’s privately owned, as are fifty-three percent of the roughly three thousand dams in Massachusetts. Located on the northern edge of the former Prospect Lake Park campground, the dam’s current owner is the Egremont real-estate developer, Ian Rasch, and his Alander Group investors. As reported in part one (and last year), they are creating a luxury “landscape hotel” on the twenty-five-acre property of the former campground, which they purchased along with an adjacent parcel nearly two years ago.

In Massachusetts, private-dam owners are responsible for their maintenance, operation, and any liability from dam failures. Which means the town, its residents, Rasch, and the dam are inextricably linked. “This is a private dam that puts a lot of private houses potentially in danger,” McGurn said at a Select Board meeting in late July.

Among elected officials, McGurn’s is not a lonely voice: His Select Board colleague, Lucinda Fenn-Vermeulen, said during a January meeting of the Egremont Conservation Commission, “All of us, it’s in our best interest to be sure that dam gets fixed. The [dam] failing could be catastrophic to the town.” She was clear, however, that any work to prevent that catastrophic result won’t be on the town’s dime. “The town can’t be on the hook for what it will cost, which will be substantial,” she said.

(As noted in part one, Fenn-Vermeulen did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Rasch also declined multiple requests for an interview.)

“This is a private dam that puts a lot of private houses potentially in danger.”

— Egremont Select Board Chair George McGurn

McGurn has been similarly adamant about who should pay. When I asked him if the town should purchase the dam to more easily access state and federal funds for repairs—as some in Egremont have proposed over the years—he was unequivocal. “It’s been raised and I have said, flatly, ‘no,’” McGurn said. The reason? “Because it’s a privately owned dam.”

Last year, not long after the Conservation Commission approved an engineer’s dam-repair plan, I spoke to David Seligman, the commission’s chair. He’s a retired philosophy professor and former college administrator who’s among the most knowledgeable environmental officials in the region. And a busy one: He recently told Egremont’s annual “all boards” meeting that in 2023, the all-volunteer “ConCom,” as it’s often called, held twenty-one regular meetings, forty-two public hearings, and made twenty-nine site visits—all part of work to “protect Egremont's land, water, and biological resources,” as explained on the town website.

When we first spoke last September, Seligman described the matter of the Prospect Lake Dam as something that’s, well, a little odd. “It’s an unusual situation. It’s a privately owned dam on a Great Pond, which is state-owned waters,” he told me. (Great Ponds are those larger than ten acres; they held in trust for the public by the Commonwealth.)

Along with the other commission members, in the summer of 2022 he reviewed that dam-repair plan and made several site visits. “We’re not experts in dam safety, but we think the plan is appropriate and adequate,” Seligman said, expressing “complete confidence” in Berkshire Engineering’s Mike Kulig, the engineer who’s repeatedly inspected the dam, designed a repair plan, and would steer any construction project. “But obviously, nobody really thinks the dam is going to fail. It’s just a question of bringing it back up to standards,” he said last year.

Still, when we talked about that possibility, Seligman pointed to the exit stream of any floodwaters. “There’s some farmland and private residences. It would be pretty horrible,” Seligman said.

How is the dam doing today? Based on Kulig’s inspections, its needs include substantial repairs to its concrete overflow spillway; construction of a new emergency spillway; permanent repair of a sinkhole; reinforcement of its walls; removal of trees and woody brush growing into the dam and its embankment along much of its 300-foot span, and replacement of a leaky, non-functioning lower-level-outlet valve.

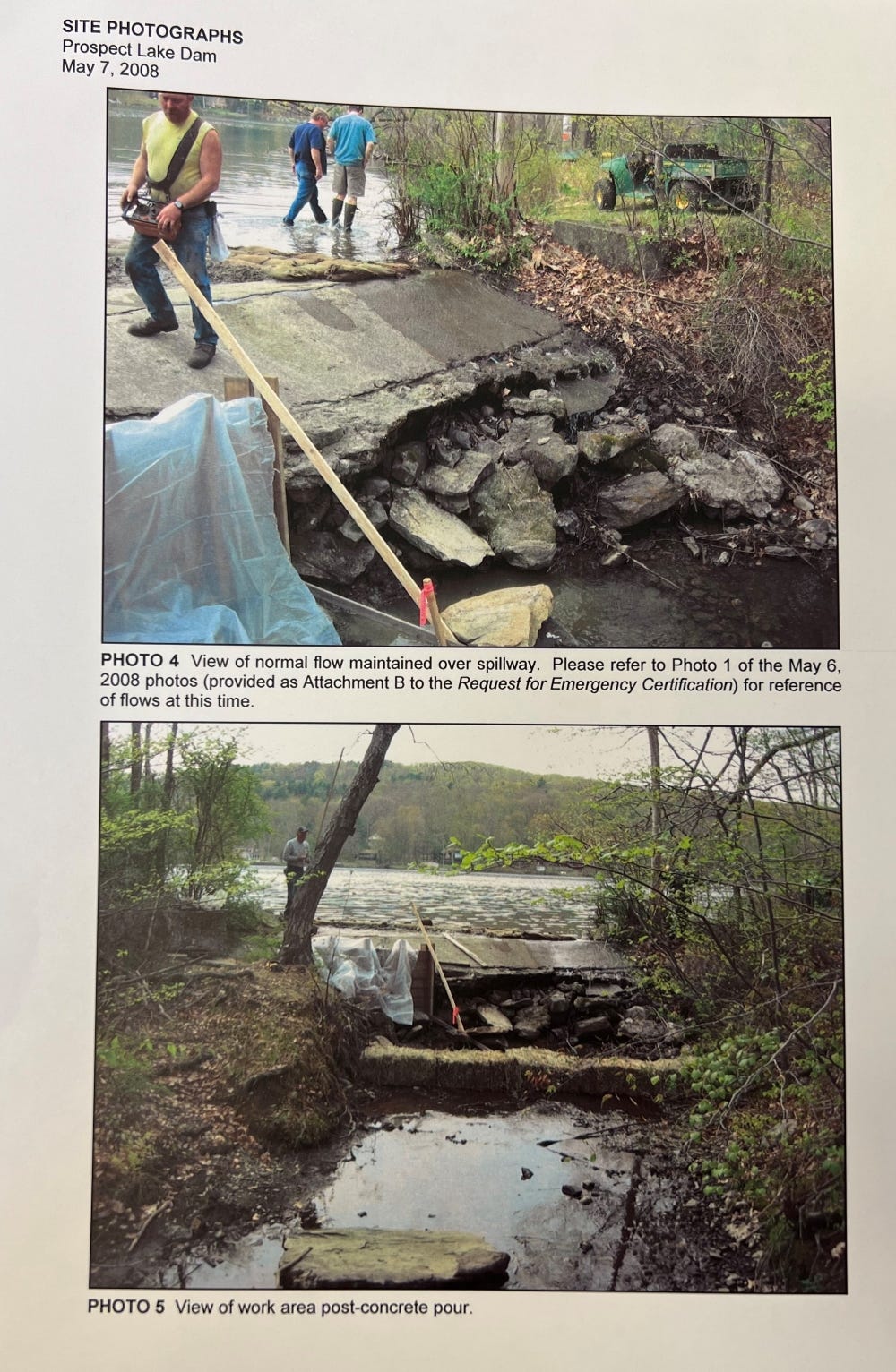

In April, an emergency fix was made to help address the worsening sinkhole, according to an updated inspection report filed with the state’s Office of Dam Safety (ODS) in July. But new issues were also found. Overall, Kulig wrote to regulators, while the dam remains in “poor” condition, it is “currently stable and continues to function properly.” He also reported that heavy rains in early summer had not made anything worse. (Emergency repairs were also made in 2008.)

While there’s no evidence that the Town of Egremont has ever spent its own funds to repair the roughly 100-year-old earthen-and-concrete dam, at least once a group of its lakeside residents did: In the summer of 1963, those with homes nearby complained about a lower-than-usual water level that was quickly traced to a substantial leak in the dam. The Berkshire County Commission, part of the former countywide government that was dissolved in 2000, ordered the campground owner to cooperate with his neighbors and address it.

Ultimately, the cost of those repairs was shared among the campground owner, a group of lakeside landowners from the Prospect Heights Association, and the proprietor of Camp Thunderbird—an adjacent property that would later be merged into Prospect Lake Park campground. (A Berkshire Eagle news story about the repairs did not include the amount spent.)

The climate emergency and old dams in Massachusetts

Regardless of cost, the need to repair this dam—and many others—is increasingly urgent. Of the 1,408 Massachusetts dams that are regulated by ODS, the one on Prospect Lake is among 213 that are in poor (180 dams) or unsafe (33 dams) condition, according to information provided to the Argus by ODS this fall.

Separate from its condition rating, the dam is included in the agency’s “significant hazard” category along with 617 other dams. That means possible loss of life should the dam suffer a major breach or full-on collapse—as well as substantial damage to public and private property. That compares to 293 dams in the top “high hazard” category, where loss of life from failure or collapse is more likely. (These categories are based on potential impacts and unrelated to a dam’s current condition.)

Worries over this dam and others come as dangerous storms and heavy-rain events more frequently stress infrastructure in the Berkshires and across the Commonwealth. A recent state climate-change assessment determined that inland flooding will be most significant among many climate hazards Massachusetts will face over the next fifty years—the result of rain totals from extreme weather.

And, at least since 2005, when former Governor Mitt Romney ordered emergency inspection of hundreds of the state’s highest-risk dams following heavy rainstorms, there have been numerous statewide studies, reports, investigations by journalists, and audits that have consistently highlighted crumbling public-works infrastructure—often designed and built a century ago for much different weather conditions. (The Berkshire Eagle’s Heather Bellow has provided excellent, in-depth coverage of dam-related stories in the Berkshires.)

Inland flooding will be most significant among the many climate hazards Massachusetts will face over the next fifty years—the result of rain totals from intense storm events.

This past summer’s notable rain events included mid-September thunderstorms that dumped up to eleven inches of rain on parts of Leominster, Massachusetts, washing away one dam and forcing an evacuation over fears a second, larger dam might be over-topped and further inundate its already-flooded downtown. (ODS staff raced to Leominster to help local officials address the emergency.)

Across the border in Montpelier, Vermont, it appeared that rapidly rising water from an early July storm might similarly over-top a dam holding back water above its downtown. With roads already flooded and impassable, trapped residents were told to go to the upper floors of their homes.

So there’s no argument from any quarter that dam safety is not an enormous and urgent challenge; it’s one that many are working hard to confront. But trying to determine how issues can be addressed soon, to ensure the safety of people and protect businesses and property, soon leads to a depressing reality: Winning the race against time to avoid catastrophe—somewhere—seems remote, particularly as the climate emergency accelerates.

That’s because these dam repair or removal projects are often large, costly, sometimes complicated, and can get delayed by extensive-but-necessary regulatory processes. Earlier this year, the Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) estimated the cost to repair all the nation’s non-federal dams at nearly $160 billion. Fixing just those in the high-hazard category will cost an estimated $34 billion. ASDSO’s estimates to repair all of Massachusetts’ dams, and the subset of just high-hazard dams, were $2 billion and $460 million, respectively.

Winning the race against time to avoid catastrophe—somewhere—seems remote, particularly as the climate emergency accelerates.

A spokesperson for ODS said it does not have a figure for repair or replacement of all of the state’s high- and significant-hazard dams in poor or unsafe condition. But it estimates the total cost at “hundreds of millions of dollars.” And while Governor Maura Healey this year has argued for more federal resources, funds are limited: The $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act—also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act—approved by Congress in 2021 allocated just $4 billion for dam rehabilitation. It was a significant sum but one that falls far short of the amount dam-safety analysts say is needed.

Even with growing attention from policymakers, the list of dam projects is not getting shorter: ASDSO suggested in an April report that because of cost and complexity, “the overall number of dams needing rehabilitation has increased due to the identification of deficiencies outpacing the completion of rehabilitation projects.”

The example of the Bel Air Dam in Pittsfield

Case in point: Last Friday, state officials were at Pittsfield City Hall to announce that $25 million in American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds will be spent to remove eight Massachusetts dams. Fully $20 million of that total is earmarked for removal of just one dam: The unsafe, crumbling, two-hundred-year-old Bel Air Dam that’s perched above an economically challenged neighborhood in Pittsfield. The rest are located on Department of Fish and Game properties in central and western Massachusetts.

Why is it so expensive to just demolish a dam? Because it can be complex: The Bel Air Dam project includes removing an estimated 355 tons of sediment held back by the dam that contains high levels of lead, chromium, and arsenic. And Jim McGrath, Pittsfield’s Open Space and Natural Resource Program Manager, told me the amount of sediment removed, and other project components, may still change as engineers complete a design plan and as discoveries are made during the work.

The Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) estimates the total cost to repair all the nation’s non-federal dams at nearly $160 billion.

That dam, located along the West Branch of the Housatonic River, was until recently privately owned. Its collapse would send floodwaters and contaminated mud across a large part of downtown and threaten the crucial Berkshire Medical Center campus. And while the state first labeled Bel Air Dam “unsafe” in 2002 and sought to force the owner to make repairs at least as far back as 2007—and then made some emergency fixes on its own—the owner ignored dam-safety orders and a state lawsuit for years. He died in 2021; the dam is now considered “abandoned.”

The officials on hand at City Hall were emphatic about the scale, danger, and need to address dam safety across the Commonwealth. “This year’s damaging storms emphasized that we have to move with urgency,” said Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA) Secretary Rebecca Tepper. “As we continue to experience more frequent severe weather events, it is vital that we address the infrastructure that is most impacted.” Urgency is unquestionably needed: Despite the widely understood risks, it’s taken more than two decades to get the Bel Air Dam project into the home stretch.

Yet even with the substantial ARPA appropriation—and justified kudos handed out to city officials like McGrath who have thrown themselves into this work—the removal project itself will not begin until the fall of 2025 at the earliest, and perhaps not until 2026. The number of intense weather events that might stress and potentially destroy the Bel Air Dam in the meantime was not addressed.

Among competing budget priorities at all levels of government—and despite the loss of life and vast cost of cleanup should a dam like Bel Air fail—there’s no Apollo-scale program to resolve all of these issues “before the decade is out,” to repeat the action-oriented words of a well-known Massachusetts politician.

Moving the ball forward at Prospect Lake Dam

So, without question, there are far more troublesome dams in the region than the one at Prospect Lake. That includes Rising Pond Dam in Great Barrington, considered to be in satisfactory condition but where nearby residents could face flooding by water polluted with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the event of catastrophic storms or a dam failure. But deferred maintenance of any dam in this new era of extreme weather can lay the groundwork for trouble.

For his part, Rasch has been clear since last fall that he will do what some other owners of the former campground property have not: Complete the full overhaul mandated by ODS and then properly maintain the dam. According to local officials, state regulators, and documents reviewed by the Argus, the repair project has finished all design work, acquired all but one necessary permit, and received preliminary bids.

“The biggest impediment [to opening in 2024] is the dam.”

—Alander Group’s Ian Rasch in October, 2022

As part of its new dam-owner responsibilities, Rasch’s company last year updated a state-mandated emergency-action plan [PDF] last revised in 2007. Aside from steps to take in an emergency, the plan describes the benefits of a repaired dam: First, annual winter drawdowns via the replaced lower-outlet valve “to control pond bank vegetation.” And second, water could be released through the valve “prior to forecast significant storm events in order to temporarily provide additional storage volume … to limit stresses on the dam structure and minimize any over-topping events,” the plan says.

If approved by state regulators, winter drawdowns may help reduce the need for herbicide treatments administered by Friends of Prospect Lake, a nonprofit organization. Performed annually for much of the last two decades, they kill invasive weeds including Eurasian milfoil, and, on occasion, are applied to address algal blooms. (Prior to any vegetation-control drawdowns, regulators would first confirm there are no threatened species of plants or aquatic animals along the lakeshore.)

In the end, and beyond any liability, Rasch has a substantial financial incentive to fix the dam. He told me last fall that he can’t get public-liability insurance for his venture and open for business until the dam is fixed. “The biggest impediment [to opening in 2024] is the dam,” he said. He’s told those in Egremont Town Hall the same thing.

That means among town officials, residents, and a new-and-motivated dam owner, there’s momentum and unanimity of purpose to get the job done. But how to pay for it? The repair plan creeping slowly through its final regulatory review will cost more than three quarters of a million dollars.

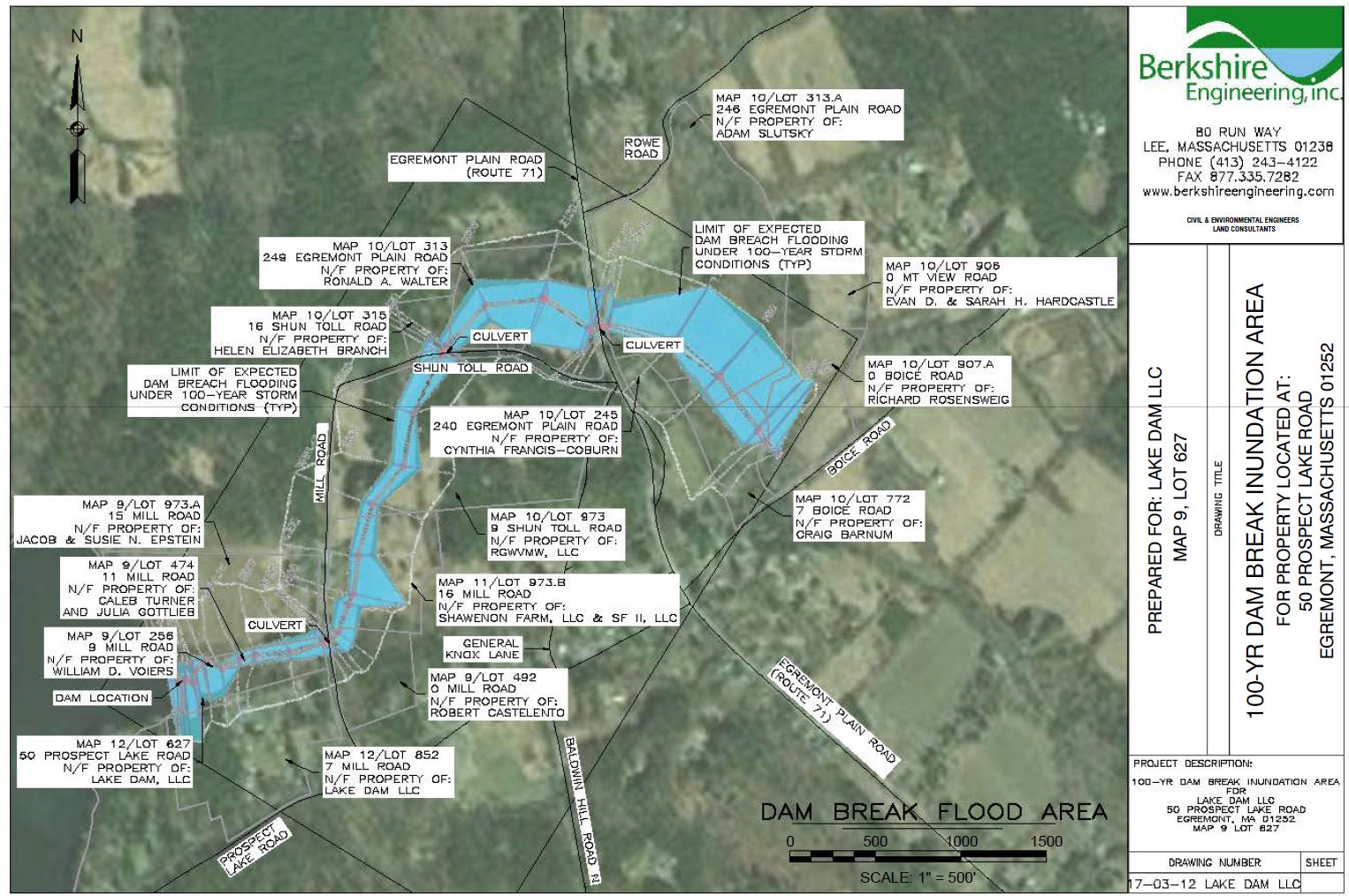

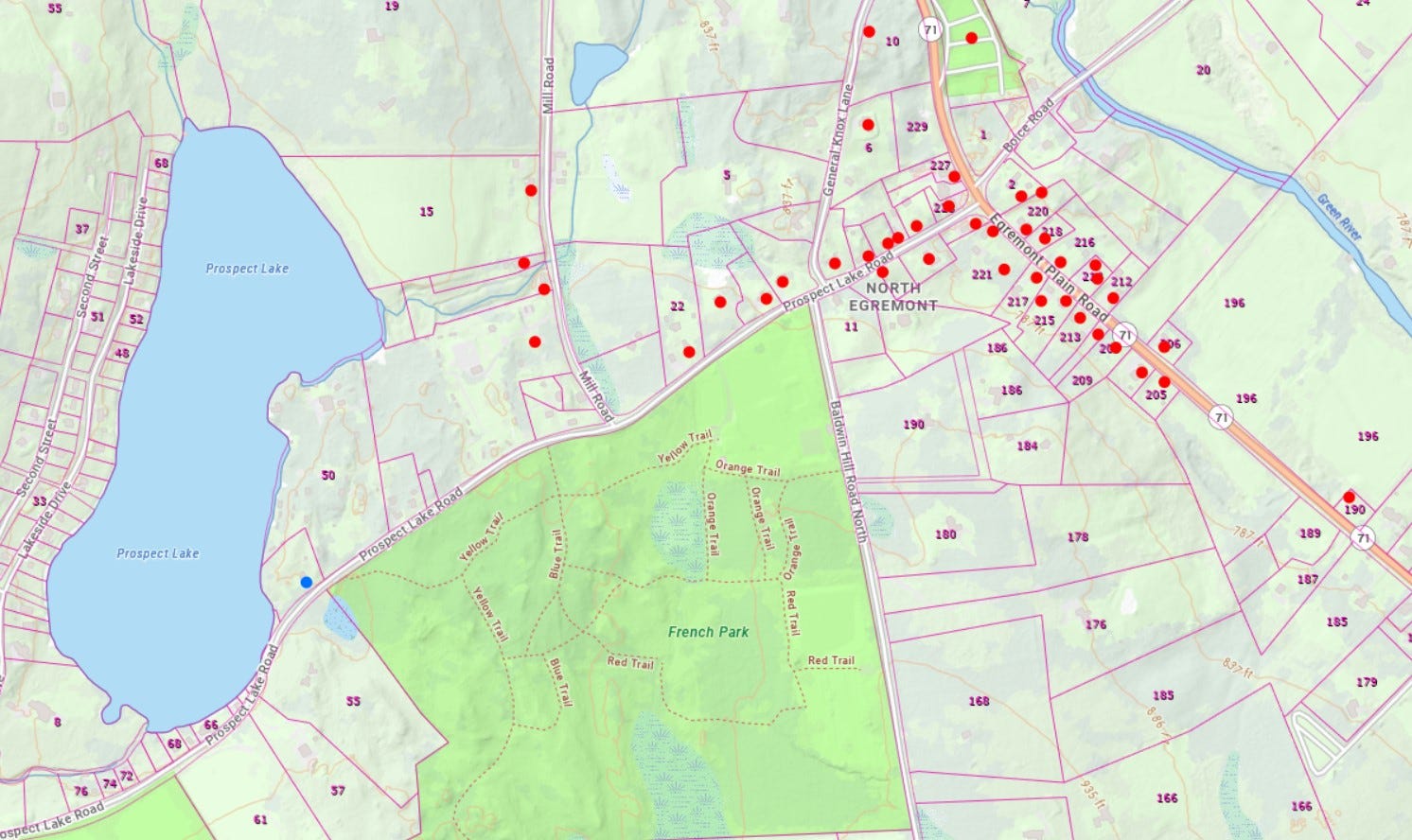

In the meantime, if the Prospect Lake Dam suffers a catastrophic collapse, properties to the north and east of the campground, and continuing across Route 71 in North Egremont, would be endangered, according to an inundation map included in the emergency-action plan. When the lake is at peak volume, the report said, the dam holds 437 acre-feet of water. In layperson’s terms, that’s more than 142 million gallons.

The question of public lake access

Since the sale to Alander Group, the future of the former campground and its dam have also become intertwined with town residents’ longstanding wish for safe and convenient lake access. Currently, most people enter Prospect Lake for swimming, boating, and fishing at what’s known as “The Gap,” a small, ten-foot break in shoreline vegetation on the north side of Prospect Lake Road that’s just steps from the water. It’s located a few hundred feet south of the former campground’s entrance. It’s a tiny spit of land that’s not publicly owned, but rather, is part of the parcel of private land across the street.

Swimmers and boaters park their cars and trucks mostly in the road, with tires barely kissing a nominal shoulder. That squeezes often-speeding traffic down to a single lane just around a bend in the road. During the summer, there’s lots of activity along the roadway, with families and young children coming and going to the water. It can get crowded in winter, too, when favorable ice-fishing conditions mean plenty of cars parked along the snowy roadside.

(One unconfirmed anecdote: In the late forties and early fifties, a former owner of The Gap sometimes spread shards of broken glass in the area to discourage public use.)

A couple of decades ago, there was also a small car-top boat launch, with parking, on the southeastern side of the lake, owned and managed by the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) and used, by law, only for boat access. (The state’s Department of Fish and Game, an agency inside DCR, posted a prominent, fun-killing, “No Swimming” sign.) But the boat launch fell into disrepair and was dismantled, and the lake’s only public water-entry location soon became impassable because of silt and weeds.

Years of on-and-off-again discussions about bringing it back have not been fruitful. Fenn-Vermeulen said earlier this year that she thinks DCR is “obligated by statute” to dredge the area, restore the boat launch, and bear all the costs. In a spring newsletter, the Select Board said it was working on it, but there have been no subsequent updates.

Over the years, Egremont residents and the public-at-large could also sometimes access the lake via the former campground property by paying a few dollars for a day pass—in the nineteen sixties it was as little as thirty-five cents for adults and a quarter for children, and another dollar to use the boat launch. But in recent years, that opportunity was dependent on the mood and availability of the former owner.

The Egremont-Alander deal for parking and dam-repair funds

Last year, Rasch, who lives nearby and has said he likes to paddleboard on the lake with his daughter, told me he was familiar with the safety issues at The Gap. He vowed to explore ways to make his new venture “a community resource” and help address parking and access issues. “We’re going to balance the required capital [investment] to bring this place back up, so it can actually function and be safe and be fun and a recreational park,” he told me, “but also provide access to local residents.”

Seeing alignment between residents’ desire for lake access and safe parking, and the need to pay for expensive dam repairs, last winter Rasch and the Select Board began a negotiation. Over the course of four meetings—held in executive session and out of public view—the three board members, Town Counsel Jeremia Pollard, and Rasch’s attorneys hammered out a swap: The town would apply for a grant from the state’s Dam and Seawall Repair or Removal Program that, if awarded, would pay seventy-five percent of the cost of dam repairs, or $577,935 of an estimated project total of $770,580. Under the program’s rules, Rasch’s company would pay the balance. (The town would administer the grant and manage the construction project.)

In exchange, Rasch would reserve ten parking spaces at the former campground property—for Egremont residents only—via a permanent easement. Anyone using the town’s parking spots could, according to the agreement, “avail themselves of the facilities … for swimming and boating.” They could also use “the pool house restrooms” from May through September. (As reported in part one, zoning approval of a new pool—for hotel guests only—and the adjacent pool house has sparked intense legal wrangling.)

The agreement [PDF] was approved by a two-to-one vote and signed on Valentine’s Day; McGurn and Fenn-Vermeulen in favor with Mary Brazie opposed. Brazie also later voted against submitting the completed grant application.

When I talked to Brazie about it a few months ago, she said she worried about financial exposure. “I think my concerns really were the town’s liability … because we were the [grant] applicant,” she said. “We were going to be held liable for the work done by the contractor.”

Notwithstanding Brazie’s concerns, the agreement includes extensive language to indemnify and protect the town from dam-related liability. It reads, in part, that Rasch’s landscape-hotel entities “agree to hold the Town of Egremont harmless for any defects in workmanship pertaining to the dam reconstruction project, as well as ongoing upkeep and maintenance of the dam.”

How that might unfold, including whether Alander Group’s liability insurance—or the financial resources Rasch may have among a latticework of nearly fifty Delaware and Massachusetts limited-liability companies (LLCs)—could make whole those impacted by a dam failure is unknown. Under Massachusetts law, private dam owners—whether an individual or a business entity—are fully liable for damages from “the operation, failure of or misoperation of a dam”; real-estate developers commonly create separate legal entities for each asset to ensure problems or liability from one don’t impact the value of others.

When I asked McGurn about the agreement in August, he said that over the years, he’s heard lots of ideas for better parking and access to Prospect Lake, none of which seemed feasible. “I always thought the only safe way was to somehow get access [via] Mill Road,” he told me, referring to a street that abuts the northeastern boundary of the campground. “As soon as I heard that the parking for this new development was going to be on Mill Road, I jumped at the chance. And it worked.”

In the town’s April newsletter, the Select Board report trumpeted the deal and described new dedicated parking “off Mill Road [that] will be near the beach for swimming and boating. This agreement will vastly improve not only access, but safety for all, including our children and grandchildren,” it said.

Fenn-Vermeulen also spoke about the agreement in several public meetings this year, describing new parking off Mill Road and guaranteed lake access. In January, she told the Conservation Commission about ongoing negotiations: “We’re pushing hard on the owner to give us what we want, which is very clear access to the lake,” she said. She described the pending deal as “a way in which the town is able to supply money to this entity, so that we can get the dam functioning [and] he can get insurance and continue his development.”

Confusion over the agreement’s terms and benefits

But the executed agreement, at least, shows something a bit different than what McGurn and Fenn-Vermeulen have said all year. Rather than dedicated parking off Mill Road, the map included with the agreement shows the town’s ten dedicated spaces will be in the landscape hotel’s new parking lot in the far southeast corner of the property. That area is directly off Prospect Lake Road—via a new entrance and driveway constructed in October—and located a fair distance from the lake: From the parking lot to the site of the campground’s former beach and recently dismantled water slide is nearly a quarter mile. The agreement map shows no parking off Mill Road.

And while Egremont residents can park in the lot, the agreement specifically blocks them from driving on any roads on the property. That was another of Brazie’s criticisms: “You have to walk basically across the whole campground to launch a boat,” she told me. She also said she didn’t know how, in practice, the promised spaces would be kept available for residents. Indeed, back in May, Rasch told the town’s Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) that he doesn’t expect to be able to monitor public use or check whether visitors using the parking spaces are from Egremont.

Seligman, the chair of the Conservation Commission who has repeatedly praised the redevelopment project’s landscaping and shoreline plans, also discounted the benefits. At a Planning Board meeting in April where the project and parking agreement were discussed at some length, he said, “People are going to continue to use The Gap, especially people with kayaks or paddleboards.”

Also excluded from parking and lake access are nonresidents, including those from nearby towns who have long come to Egremont to enjoy this state-owned lake and south Berkshires amenity. Presumably their only option will be to use The Gap.

Other drawings of the property included with unrelated town filings, as well as an undated site drawing posted online by a project designer, suggest plans for a small parking lot immediately off Mill Road. It’s located at the far northeastern corner of the property—about 900 feet from the closest lakeshore and 1,500 feet from the former water-slide location. But it’s not referenced in the agreement.

McGurn later told me, in October, that he thought the agreed-upon parking was off Mill Road. But in any event, he said, the most important thing is to get cars off Prospect Lake Road at The Gap. “It’s off the road, that’s all I care about,” he said.

Are benefits to the town contingent on securing state dam-repair funds?

Whether due to sloppy legal drafting or for other reasons, the agreement’s language leaves unclear whether Alander’s parking and lake-access commitments are contingent on actually receiving dam-repair funds from the state: All the promised benefits come after the words, “If a grant is awarded.” That legal uncertainty may become relevant because, in mid-July, the state denied the town’s application.

McGurn said the denial was at least in part because the project didn’t have all required permits from local, state, and federal authorities. He told me in August that the only missing permit was from the Army Corps of Engineers, which has since been issued. But a license for work on the dam—and on a nearby unlicensed dock—has not yet been issued by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP), under the Chapter 91 Public Waterfront Act.

Seligman told me recently that acquiring a license for Chapter 91-related work in public waters can be onerous—and sometimes take years. He called it “the slow, grinding wheels of state bureaucracy.” Despite that requirement, Alander’s application was not initially filed until mid-July this year—five months after the grant application was submitted—and because of omissions and state-required corrections, was not complete until this fall, according to information provided by MassDEP.

Missing permits were certainly a factor in the denial; grants under this construction program require that all permits are in place and the project is “shovel-ready” for work in the current fiscal year. But it may face other hurdles: A spokesperson for the state’s Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA), which oversees the grant program, told me that while the program has, over its ten-year history, awarded funds for private-dam-removal projects, it has never funded repairs to a privately owned dam. (Removal of unnecessary dams has long been championed by environmentalists and can often be far less expensive than repair.)

Egremont’s public-private partnership to access state funds for repairs is also novel and untested. “Until this year,” the EEA spokesperson said, “no applicants have proposed a partnership of this kind for a dam-repair project.” McGurn noted that very challenge at a Select Board meeting this summer: Referencing a conversation with the town’s grant administrator, he said, “A public dam is always going to be first in line [for state funding], and this is a private dam.”

Still, McGurn told me that he remains upbeat about winning the grant in the next cycle. “We’re still in it,” he said. “We’re quite optimistic about the approach we took, so we’re on a steady course.”

But McGurn is also convinced the outcome doesn’t matter as far as the parking-and-access agreement with Alander Group is concerned. “The town of Egremont has fulfilled its responsibilities by producing a first-rate grant application,” he told me in August. “Public access to the lake through the campground was not dependent on us getting the funding. It was dependent on us producing the proposal,” he said. “I happen to believe Ian is a trustworthy person,” he added, “and we have an agreement.”

Although the February agreement includes a permanent easement for parking and access, none have been filed with the registry of deeds as of early December.

“Public access to the lake through the campground was not dependent on us getting the funding. It was dependent on us producing the [grant] proposal.”

—Egremont Select Board Chair George McGurn

Politically, McGurn is heavily invested in the outcome, frequently touting the agreement and its benefits to town residents. Shortly before it was signed, he told a Zoom meeting of committees working on the town’s comprehensive plan that it was a big deal. “[It] will not just give access to the lake,” he promised, “but also be a giant step toward solving the very dangerous issue of the current use of The Gap.”

The challenge for dam regulators—even with enforcement tools

Besides an indeterminate countdown to the landscape hotel’s eventual opening, and whether extended delays will create additional zoning-related challenges, there’s another clock ticking: Earlier this year, ODS ordered that the Prospect Lake Dam be fully repaired by October 1, 2024. And under state law, the agency can impose penalties on dam owners who don’t comply, as it tried to do with the former owner of Pittsfield’s Bel Air Dam. According to the dam-safety order [PDF] sent to Alander Group, acquired by the Argus, the company could be fined as much as $5,000 per day if it misses that deadline, which is just ten months away.

That sounds like a potentially motivating sanction. But when I asked ODS for a summary of fines levied on private dam owners during the last five years, the agency’s reply suggests that it rarely, if ever, uses that authority. “Rather than collecting on fines that add to already costly, necessary dam repairs, ODS works with dam owners to bring dams into compliance,” a spokesperson told me in September.

That highlights the challenge facing ODS’s twelve-person staff, municipalities, private-dam owners, and the public as climate-change impacts grow more significant: Many dams are old and repairing them is expensive. So, whether in Egremont or Pittsfield or elsewhere, necessary work is frequently put off—especially by dam owners with limited resources. The EEA spokesperson told me that’s why the dam-and-seawall grant program was established: “Without this program, the cost to remove or repair many dams can be prohibitive for owners without financial assistance,” the spokesperson said.

But if the state’s dam regulator declines to enforce its orders by imposing and then collecting financial penalties, repair timelines can drag on indefinitely.

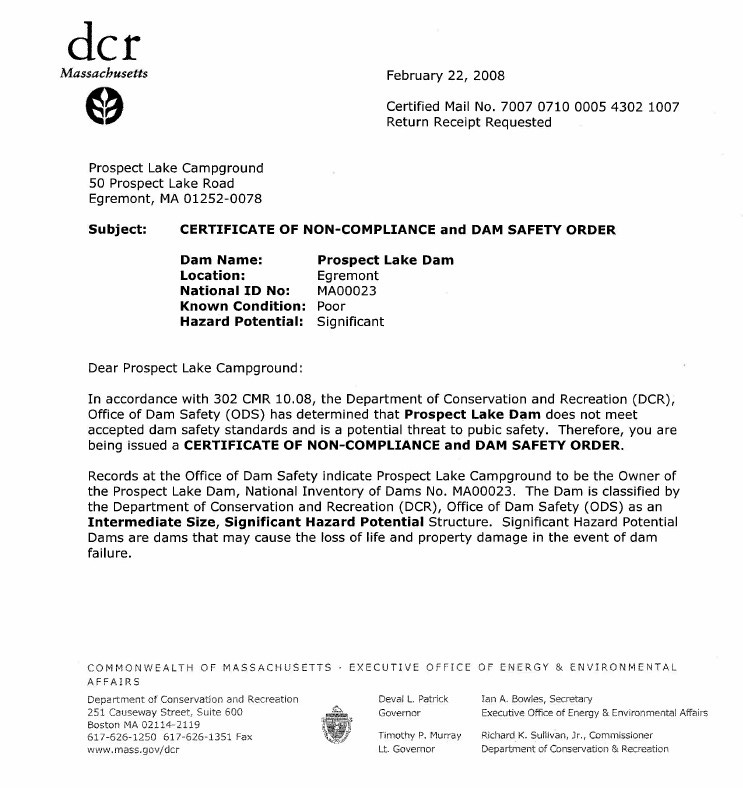

That’s certainly been the case in Egremont. A formal notice of noncompliance was first issued by DCR after a 1999 inspection found the Prospect Lake Dam “structurally deficient” and in poor condition—as it remains today. That inspection followed, by nearly a decade, a 1991 state-subsidized study [PDF] that examined both the overall health of Prospect Lake and the condition of the dam. Remarkably, the 1991 study noted that issues documented during an earlier inspection, in 1974, still had not been addressed—fully seventeen years later.

ODS followed up with additional noncompliance notices and dam-safety orders in at least 2008 and 2015, but little was done. The 2008 order [PDF] set a repair deadline of “November 31, 2009” or, it said, fines of $500 per day were possible. (Presumably, “31” was a typo and not a wink to the campground owner that the deadline was fictional.) Some emergency repairs completed in 2008 were not enough to upgrade its condition rating from “poor”; the dam-safety order remained—and remains—in effect.

According to documents reviewed by the Argus, these notices were also sent to Egremont’s elected officials and emergency-management contacts, including the Select Board and Conservation Commission. Not that anyone needed reminding: A 2012 Berkshire Regional Planning Commission hazard-action plan developed with officials of south-county towns, including Egremont, listed “continue working with DCR to repair Prospect Lake Dam” as a high priority. The goal? “Reduce the risk of failure and subsequent flooding.”

And an update to the town’s hazard-mitigation plan issued last year called for “coordinat[ing] with state and private owner on next steps for updating Prospect Lake Dam.” That action item was, once again, listed as “high priority.”

The town’s recent dam-repair grant application [PDF], acquired in full by the Argus via a state public-records request, noted that town officials had previously engaged with the former campground owner and “pressed him unsuccessfully” to make repairs—pressure they believe made him uncooperative in conversations about providing better lake access to residents.

But even as time went by, each year the campground continued to apply for, and receive, all necessary local permits to continue operating. That includes several annual permits from the town’s Board of Health (BOH), including to operate a campground and for a semi-public beach.

Juliette Haas, the current BOH director in Egremont, told me in an email that the board didn’t withhold permits or take action against the former owner, who, she said, “flat-out refused to take responsibility for the dam.” Haas said that Egremont’s board works to encourage compliance, even though it does has broad authorities under the state’s public-health statutes. That mirrors both the challenge and approach taken by dam-safety regulators who must balance carrots and sticks to achieve good outcomes.

By way of comparison, she pointed to Rasch’s substantial engagement with the town and the Select Board since Alander Group acquired the dam, which she called “progress.” As with any matter, she said, action by the BOH on any board-issued permits would be discussed in a public meeting by the entire board.

The path from here on dam repairs

In November, 2021, the former owner, Jim Palmatier, hired Kulig and Berkshire Engineering to conduct an overdue dam inspection and begin work on a full repair plan. That inspection report confirmed the poor condition of the dam and estimated the cost of repairs to be $250,000. (Based on documents reviewed by the Argus, a plan for partial repair was submitted to state regulators by Palmatier in 2018 but the project did not advance.)

Whether he was motivated to focus on the dam by pressure from town officials, state regulators’ threat of fines, or the terms of a purchase-and-sale agreement with Alander Group is unknown. But Palmatier sold the campground, and its ailing dam, a little more than two months later.

The spokesperson for ODS told me that since taking ownership, Rasch’s company has worked with the agency and “is in compliance ODS.” The repairs required by the dam-safety order will take between four and six months to complete, depending on variables like weather and the length of any public-bidding process. But the work can’t start until permitting is complete: The outstanding Chapter 91 license from MassDEP that allows work in public waters remains “under review,” according to a state database of environmental-permit applications.

MassDEP spokesman Edmund Coletta told me last week that a mandated public-comment period on the repair plan ended in mid-November. But because of a procedural blunder—Alander Group failed to send the plan and notice of the comment period to abutters, municipal officials, and others—that part of the process must be repeated, he said. More generally, Coletta told me last month that he couldn’t provide a specific timeline for when the agency might conclude its review and issue the license.

Even if the town reapplies for state funds under the same dam-repair-grant program, the money may come too late for a developer eager to open his landscape hotel for business. The new grant cycle has not yet started, an EEA spokesperson told me this week, and grant awards are not likely until next summer.

There are hints, at least, that Rasch may not wait: Not long after purchasing the campground, the dam parcel was moved into a separate Alander Group entity called Lake Dam LLC, likely to protect the hotel enterprise from dam-related liability. (The town’s grant application sought funds for Lake Dam LLC.) But shortly after the grant denial, the property was transferred back to the primary landscape-hotel entity, 50 Prospect Lake LLC, according to documents filed with the registry of deeds. That could enable Rasch to tap mortgage-loan and private-equity resources to fund the dam project as soon as the final MassDEP permit is in place. Otherwise, waiting for a state grant award could push the dam project into late 2024 or early 2025.

What all of this means for dam repairs and lake access—that, depending on how one reads the Egremont-Alander agreement, may be contingent on a successful grant application—remains difficult to discern. Seeking more details about the discussions that led to the deal, an Argus public-records request in late September forced the Select Board to release minutes [PDF] from the four executive sessions held last winter. But they included no details at all, noting only that the board discussed an agreement and sought a permanent easement.

What kind of lake access will actually be available?

Another significant unknown is what the promised lake access will mean, in practice, given the extensive remaking of the former campground—as well as the Egremont-Alander agreement’s lack of specificity.

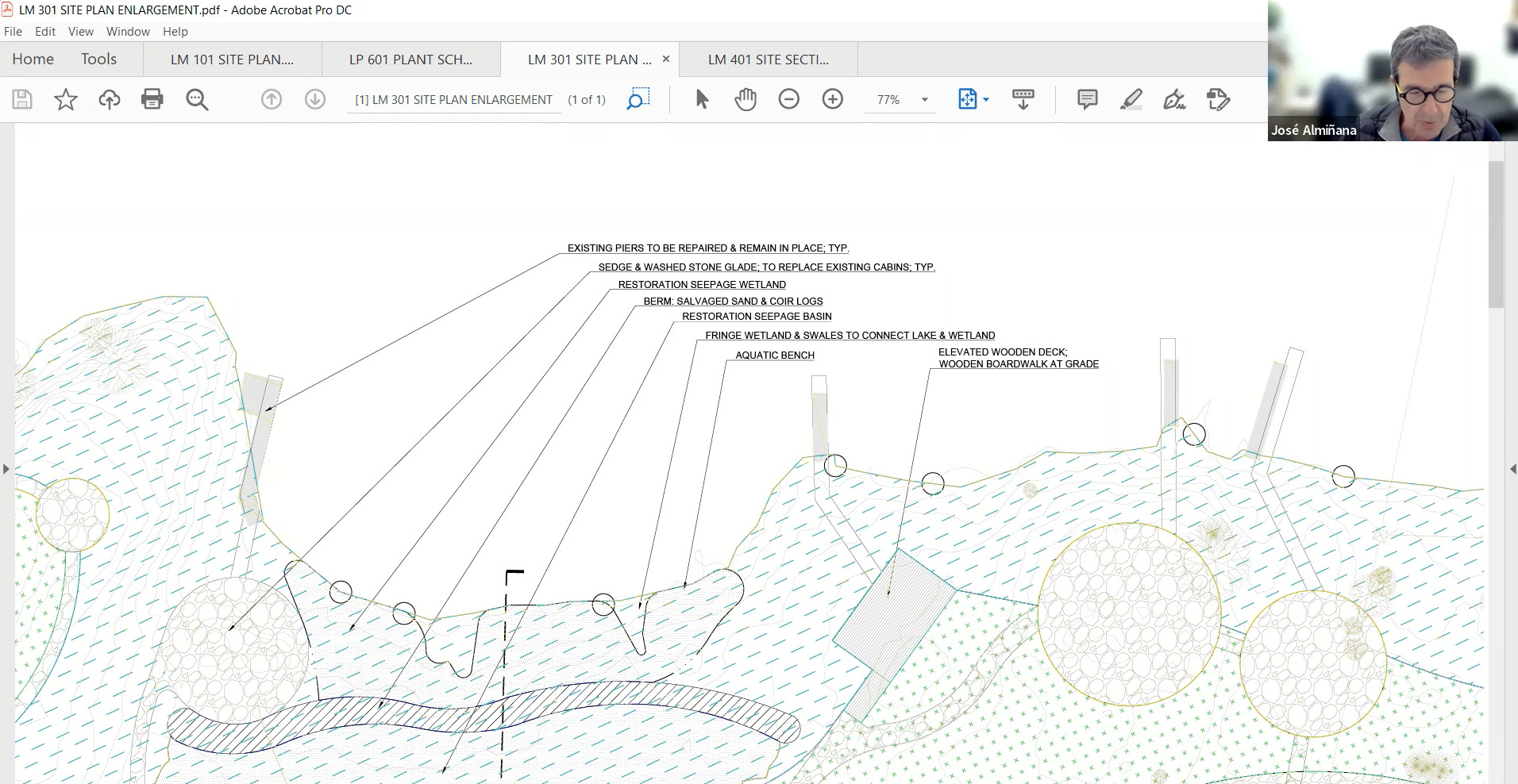

For instance, at one Conservation Commission hearing last winter, José Almiñana, the accomplished landscape architect working on the project, described how the property’s new design will naturally manage and filter storm water to protect and improve the lake’s water quality—an important element of climate resilience. “Having done all that,” he continued, “we’re also limiting the amount of access that people will have to the lake. And that way we also seek to protect that resource.”

Similarly, the town’s dam-repair-grant application—which, based on public discussions between Select Board members and the town’s grant administrator, Margaret McDonough, was written largely by, or at least in close collaboration with, Alander Group—suggests the former campground’s lakeshore and “restored wetlands” are meant primarily for viewing, rather than for activity. The application summarized the benefits of the “shoreline restoration” as “improved water quality, attracting or reestablishing native species’ habitats, limiting human disturbance in sensitive areas, capturing floodwaters, limiting runoff, and creating a quiet zone suited to more passive outdoor pursuits.”

That aligns with something Rasch told the ZBA in May: “We’re trying to create a nature-based experience,” he said of his plans, “which includes being respectful of the lake and the habitat around it.”

How that translates into recreational opportunities for Egremont residents on, and through, the landscape-hotel property remains to be seen. Because it appears that Egremont’s Select Board was not provided full details of the landscape hotel or how it would operate, McGurn and Fenn-Vermeulen, the two members who voted for the agreement, may have assumed that beach-going and swimming would be similar to what was available at the former campground. But all evidence is that it will be far more limited.

Joyce Frater, who serves on the Conservation Commission and as president of Friends of Prospect Lake, wrote about the broad range of lake recreation enjoyed by residents in the nonprofit’s letter in support of the town’s grant application: “We have birders, swimmers, summer and winter fishing, canoeing, kayaking and paddleboarding. We encourage and welcome swimming, including senior swimmers.”

With access to the water only via piers out into the lake, as Rasch told the Conservation Commission last year, will there be ladders to help those swimmers—a quarter of Egremont’s full-time residents are 65 and older—with water entry and exit? And as Brazie wondered, where will residents put boats into the water if they are able to transport them from a distant parking lot?

A general lack of specificity, along with expansive claims about public access and available amenities, is evident elsewhere. Letters of support for the grant application—including those from State Senator Paul Mark [PDF] and State Representative William “Smitty” Pignatelli [PDF]—used identical verbiage to tout the agreement: “The most important benefit from the Town’s and the region’s perspective,” their letters say, “is that the public right of access to this Great Pond will be restored, by virtue of a separate access agreement that provides use of campground facilities, including designated parking, water access, restrooms and food concession.” (It’s unclear what food concession, if any, will be offered to Egremont residents; none are referenced in the agreement.)

Perhaps most complicated is how the peaceful ambience promised to landscape-hotel guests will mesh with, potentially, a steady stream of enthusiastic water-frolickers. Opening the hotel’s carefully restored shoreline “quiet zone” to, say, carloads of rambunctious Egremont teens and their friends—perhaps celebrating a milestone birthday or recent graduation—brings to mind the Caddy-Day-at-the-pool scene in the 1980 Chevy Chase and Bill Murray country-club comedy, “Caddyshack” (The film’s promotional tagline? “Some people just don’t belong.”)

As in the movie, how will hotel staff and patrons handle noise or activity that might exceed that from “more passive outdoor pursuits”—and what’s expected by guests who may have paid, based on rates at a similar landscape hotel in the Catskills, five hundred dollars a night? Under the agreement with the town, Alander Group “reserves the right to expel or bar any person engaging in illegal or inappropriate behavior,” but there’s no definition of “inappropriate.”

Interest and concern from the Egremont Historical Commission

Given that nearly seventy percent of respondents in a town survey last winter listed historic preservation as a priority, it’s not surprising that the Egremont Historical Commission has shown great interest in the project. The campground, which began life as a popular picnic spot for residents and visitors, has been a part of the community since the 1870s.

The commission, established in 1974, has discussed the campground and its historic buildings during a number of meetings this year. It also spent months seeking information about ongoing work at the site and plans for renovations and demolitions.

At a meeting held a few weeks after the May 15 zoning hearing, the commission spent a half-hour discussing the project. They expressed mixed opinions about renderings of the new, “very modern” Cliff House shown to the ZBA. One commission member reported that the developer was said to be “not sentimental” about preserving the history of the former campground.

Cognizant of its lack of formal tools, the commission sent a letter [PDF] encouraging Rasch to consider restoration as much as renovation as his team remade historic structures. “While Cliff House has evolved over its almost 150-year lifespan, losing much of its original architectural character,” the July 13 letter said, “it is our hope that you and your design team embrace this building’s history and meaning with a sensitive restoration, bringing back to life a piece of Egremont’s history.”

Rasch never replied. “We did what we could,” the chair, Rebecca Turner, said at the commission’s next meeting.

Other commission efforts were also stymied: Members complained they couldn’t get access to the campground property to inventory its buildings for a state database of historic structures—ideally before any were demolished. “Difficulty getting permission to photograph old Prospect Lake campground,” noted minutes of one meeting.

Beth Wood, a commission member with more than two decades of experience researching the history of Berkshire County properties—and who also serves as Egremont’s town historian—has been leading the effort to update state records of the town’s historic properties. At an August commission meeting, Wood said she still couldn’t get clear information about the age or style of buildings at the former campground property, or if any had been demolished. “I have no idea, and that’s a bit of a problem,” she said.

“I wonder if anyone has a drone,” joked commission member Barbara Kalish.

McGurn, the Select Board chair, seemed to have a different understanding of the commission’s feelings. “There’s the Cliff House, and I’m not quite sure what state it’s in at the moment, which is going to be restored,” he told me in August. “That actually has some historic value. And there’s also a rec building that’s also being restored. And that makes the Historical Commission happy.”

Recent experience may have spurred the commission to accelerate its work on a “demolition-delay bylaw.” On the books in at least 160 Massachusetts cities and towns, including nearby Stockbridge, Lenox, Pittsfield, and Sheffield, it enables a construction pause for conversations with property owners who plan to demolish or significantly change the exterior of a building considered historic. Any discussions are advisory; the bylaw doesn’t prevent demolition. Still in draft form, it will soon go to the town’s Planning Board for feedback.

An occupancy-tax windfall?

One little discussed benefit from the landscape hotel—and something that could help win any needed board approvals—is the potential for substantial new hotel-occupancy taxes added to the income side of Egremont’s roughly six-million-dollar annual-operating budget.

While state and local occupancy taxes are not levied on traditional campsites in Massachusetts, a spokesperson for the Department of Revenue (DOR) told me that, in general, that’s not the case for permanent tents or campers rented to guests.

“If a visitor rents a campsite where they pitch a tent or park their own camper, then the state and local room occupancy excise does not apply,” the spokesperson told me in October. But if the enterprise is operating as a licensed hotel, the spokesperson said, and a visitor rents a camper or tent that’s already on site, their stay is subject to both state and local room-occupancy taxes. (The landscape hotel’s park-model-RV cabins are considered, for regulatory purposes, to be parked campers that belong to the venue.)

That means guests are likely to pay both the 5.7 percent state occupancy tax, which goes to the Commonwealth’s general fund, as well as the six percent local-option occupancy tax, which goes to the town. Egremont voters approved that tax and an additional three percent short-term rental (STR) “impact fee” at their June 2021 annual town meeting.

All of this means far more local tax revenue than was generated by the former campground. That now-shuttered business was registered with the state as a hotel and would have charged occupancy tax only on stays in its handful of cabins, but not at the one hundred twenty-five campsites used for tents, RVs, and pop-up trailers brought by patrons.

According to revenue data provided by the town, Egremont has collected $220,522 in local occupancy taxes since the new levies went into effect two years ago—largely from the combined nine-percent local tax charged on the town’s seventy-seven registered short-term rentals (STR). And that revenue has been increasing year-over-year thanks to steady growth in the number of STRs: $50,347 in fiscal year 2022, $100,754 in FY23, and in FY24, a total of $69,422 through September 30.

If the landscape hotel offers its 40 cabins at rates comparable to the nearby-and-similar Piaule Catskills landscape hotel, where nightly fees start at around $499, at full occupancy that means roughly $1,200 per day in new local tax revenue. If the venue is open for the same five-and-a-half months each year as the former campground, and is fully booked, it could generate more than $200,000 in those taxes each year. Depending on the landscape hotel’s food-and-beverage offerings, there may also be substantial meals taxes collected.

Zoning, history, and the former campground’s future

If it’s not an old adage, it certainly could and perhaps should be: Most small-town stories are, in the end, somehow connected to zoning. (Another adage: If you want people to read a story—especially a long one—don’t put the word “zoning” in the headline. And consider avoiding the topic entirely.)

At full occupancy, the landscape hotel could generate more than $200,000 in annual occupancy-tax revenue for Egremont.

As reported in part one, Alander Group’s attorneys argue that a May, 2023, ZBA decision to award a single building permit for renovation of the Cliff House has, in effect, blessed the entire project and its planned use—even though the full extent of that use was never explained. During a ZBA meeting last week, Egremont’s town counsel vehemently disagreed.

So whether an Alander attorney’s threat of “serious consequences for the town” if building permits are denied will be the end of a brief zoning dispute or mark the start of a much longer, potentially expensive one is likely to be determined in the coming weeks.

The zoning questions arrive at an interesting moment: Just this week, Egremont’s Planning Board began a year-long, consultant-led public process to overhaul the town’s zoning bylaw in support of the new “Egremont Vision 2035” comprehensive, open space, and recreation plans—which were also shaped by substantial public input. Any bylaw changes would, of course, have little or no impact on what’s in place at the former campground when revisions are enacted. But the simmering dispute with Alander Group may help inspire new rules that enable the town to guide future development of campgrounds or other hospitality ventures.

It wouldn’t be the first time the town implemented campground-specific rules. In April, 1966, as the Planning Board worked on what would become the town’s first zoning bylaw, it hired a planning consultant to help navigate a host of questions. At a public meeting attended by three-dozen residents, there was great interest in addressing “house trailers” and broad concern about “trailer parks.”

In response, the consultant questioned William Carroll, then the owner of Prospect Lake Park, about sanitary conditions at his campground and explored the impact of hosting, on weekends, between sixty and one hundred fifty camping trailers. Carroll explained the state’s sanitary-code requirements and how he complied.

Then, as now, there was discussion of how to treat mobile homes and “travel trailers” on wheels—whether used for camping or as a short- or long-term residence. The zoning consultant noted that over the border in New York, “trailers on permanent foundations are legally considered single-family dwellings” but those mounted on wheels were not, he said. That sounds little different than today’s debate about the ever-more-house-like park-model RVs, which are built atop a chassis and wheels.

According to the Eagle’s coverage of that 1966 meeting, there was “general agreement that regulations are needed.” And indeed, the town’s first-ever zoning bylaw was enacted ten months later with a ban on trailer parks “not already existent,” thereby exempting Prospect Lake Park and its camp trailers and RVs. (The campground also retained preexisting nonconforming status.)

The town’s current bylaw, in a section titled “Travel Trailers and Mobile Homes,” maintains that restriction: “There shall be no other trailer parks or trailer camps established in the Town of Egremont,” it says, “other than those in actual operation and existence at the time of adopting the Bylaw.”

Fast forward fifty-seven years, almost to the day: Jared Kelly, a local real-estate agent and the energetic leader of Egremont’s Planning Board, reacted like many others upon hearing limited details of Rasch’s landscaping plans, RV cabins, and news of a deal with the town for parking and lake access. At the end of a campground discussion with Fenn-Vermeulen and Seligman at an April board meeting, Kelly said, “Everybody has different perspectives on what camping means or what it should be. But to have a local developer who cares about the environment and is looking to give public access, I think the town should be happy. We could have someone who doesn’t want to do those things.”

McGurn told me that he knows some people are upset about the closing of the former campground and the property’s redevelopment. “There were people that had come up there for years, and I’m sure they were, and are, disappointed,” he said in August. But he spoke favorably of Rasch’s project, pointing to what he said was anecdotal evidence, at least, that the former campground had deteriorated. “I think it’s an improvement,” he said. “It was run down. It needed a lot of work, and not just ecological work.” McGurn also noted Alander Group’s willingness to help some longtime summer patrons relocate their RV campers to nearby campgrounds.

“To have a local developer who cares about the environment and is looking to give public access, I think the town should be happy. We could have someone who doesn’t want to do those things.”

—Egremont Planning Board Chairperson Jared Kelly, in April, 2023.

Brazie, the longtime Egremont town-office administrator and Select Board member, still hasn’t shared an opinion on Rasch’s plans. She told me earlier this fall that her family is often out on Prospect Lake, row-boating and fishing. And like many longtime Egremont residents, she has childhood memories of the campground: Her family would sometimes camp there, she said, “and I took swimming lessons at the campground growing up.” (Lists of children who passed their swimming tests there were regularly featured in local newspapers.)

Gary Leveille, the writer and historian who spent summers at Prospect Lake Park as a teenager and young man in the nineteen sixties and seventies, has watched the property begin its transformation into a landscape hotel. (In what must surely sting, excerpts from his detailed history of the campground and North Egremont, “Eye of Shawenon,” have been used as exhibits in Alander Group zoning filings.) But he sees at least one bright spot.

“Normally by now, lakefront property like this would have been covered by cottages, houses, or condos,” Leveille told me in an email. “This new project will still allow most of the property to remain open and accessible, and that’s a good thing.”

But that doesn’t mean he’s thrilled that a landscape hotel will replace something that played a formative and important role in his life. “The sad thing is that affordable camping is now gone forever,” he said. (Rasch has countered that there are still affordable campgrounds located over the border in Columbia County, New York.)

As for the promised lake access, Leveille is unimpressed with the town’s agreement with Alander Group and what it appears to offer. “Great Ponds are supposed to be accessible by the public. That doesn’t mean just getting to look at the lake,” he said. “‘Accessible’ means actually getting to the lake, getting on the lake, and getting in the lake.”

But he placed the duty to ensure meaningful access to Prospect Lake elsewhere: State officials, he told me, have “a responsibility and an obligation” to transform land at the former state-owned boat launch into something workable for Egremont residents and the broader public.

Others seem content with plans to remake the former campground into something that’s more beautiful to behold. Fenn-Vermeulen, who was endorsed by a group of Egremont business owners, including Rasch, when she first ran for Select Board in 2019, has repeatedly praised the project. “He is doing wonderful things in terms of being very careful to hire the most able, most modern folks,” she told the Planning Board in April. “What they’re doing with native plantings and so forth, it’s just going to be spectacular.”

∎ ∎ ∎

(Read part one of this two-part story.)