At the former campground, a zoning disagreement is escalating while questions linger about public parking, lake access, and vital dam repairs. An occupancy-tax windfall is also on the horizon.

(This is the first of two parts.)

∎ ∎ ∎

It’s been nearly two years since Ian Rasch, the real-estate developer, and his private-equity-backed Alander Group spent $2.5 million to acquire the historic-but-aging Prospect Lake Park campground, and an adjacent property, located along two thousand feet of lakefront in the town of Egremont.

In multiple interviews last fall (see the “The Developer” series and its campground installment), Rasch described an expansive—and expensive—vision for an “ecological restoration” and upgrades that will “re-imagine” and “elevate” the facility to appeal to what he called “a population of people looking for some other things.”

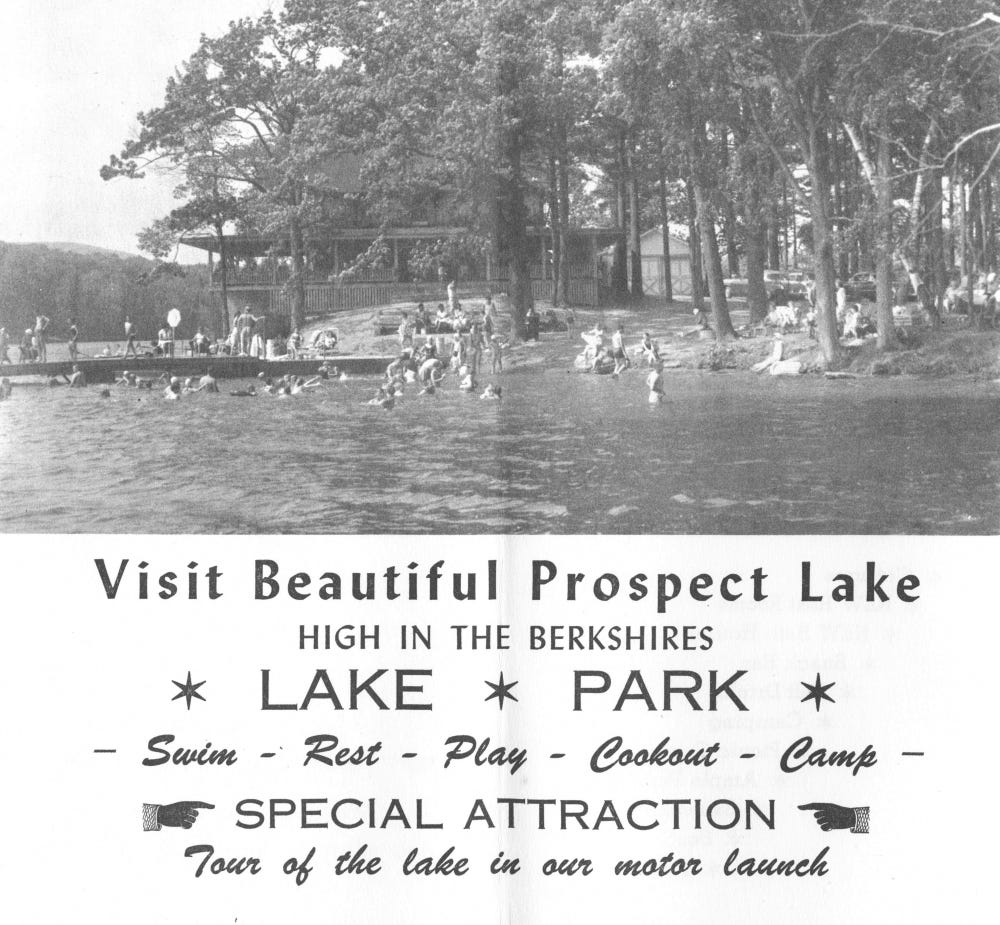

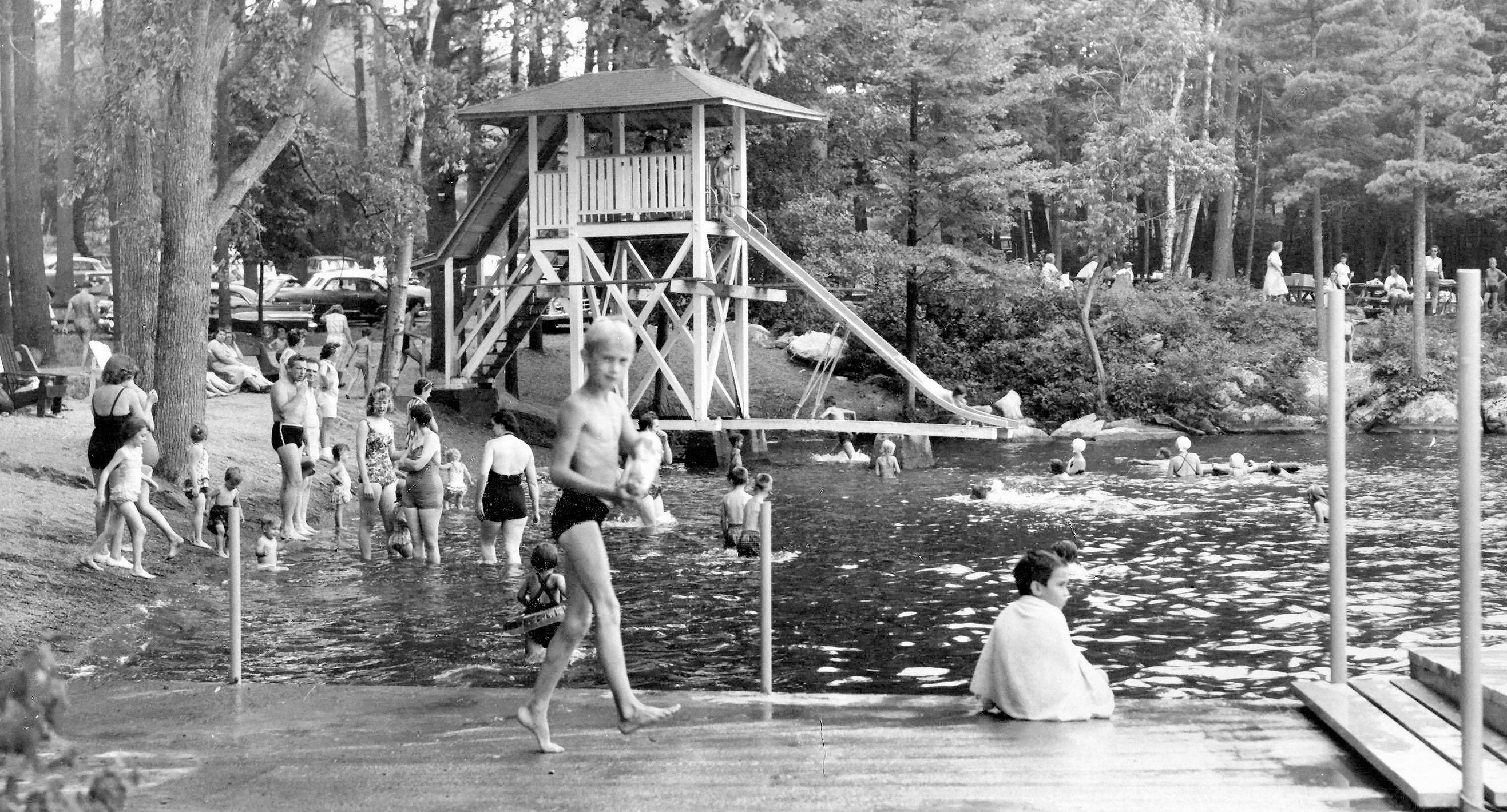

The purchase immediately rankled those who had long patronized the venue. For generations, seasonal campers spent memory-making summers at the campground with their kids, extended family, and friends. They parked their recreational vehicles (RVs) and pop-up campers at hook-up sites that cost about $2,500 to lease from May into October. Or they rented one of the campground’s rustic cabins for a week, or pitched a tent at one of the twenty-five-acre property’s campsites for just thirty-nine dollars a night, all to enjoy swimming, boating, campfires, cook-outs, and traditional campground recreation.

And, of course, to enjoy each other: For well over half a century, many of the same families returned year after year, their children growing up together on the campground’s beaches, squealing while hurtling down a huge water slide, and roaming the grounds barefoot while making general summertime mischief.

Most of those families assumed, correctly, that the sale meant a once-affordable Berkshires amenity would soon be replaced by something very different—and, no doubt, designed for those with far more money to spend.

An engaging, successful, environmentally minded, and sometimes controversial Berkshire County developer, the forty-six-year-old Rasch has said that the campground’s former owner neglected the property’s water, sewer, and electrical infrastructure for years, leaving it dangerously run-down. He pointed to electric meters and wires “hanging on trees,” outdated cabins, and decades-old camping trailers left on-site that were “filled with rodents.” Also ignored, he said, was a long-needed overhaul of a vital-but-ailing, three-hundred-foot-long, concrete-and-earthen dam on the property—one that’s been flagged by state regulators for years. (Recent estimates of construction costs for the dam’s repair run to three quarters of a million dollars.)

While he concedes the new venture will be more expensive, Rasch has compared it to his other projects, like the redevelopment of the historic, mixed-use Mahaiwe Block in downtown Great Barrington. Sure, rents were low in that building before he bought it. But, he said last year, without the substantial investment he and his investors will make to gut and renovate the building and create new, energy-efficient, luxury rental apartments, the entire structure—including its aging heating, plumbing, and other mechanical systems—would, he claimed, soon become nonfunctional.

The campground, he told me, was still affordable only because the former owner didn’t invest in a host of needed upgrades. And, therefore, the property’s overall condition—and the experience for visitors—had both deteriorated substantially.

Rasch’s assessment wasn’t just pulled from the air: Over its final decade, the poor condition of Prospect Lake Park’s facilities were described in unfavorable online reviews. There were also steady complaints about unfriendly treatment by the former owner, whose patience for customer service was perhaps depleted after a quarter-century running a hands-on hospitality enterprise with little help.

Still, longtime patrons told me last year they found the facilities adequate. And they described that former owner, a onetime auto-parts salesman named Jim Palmatier, who purchased the campground with his wife, Kathy, in 1997, as a colorful-if-sometimes-grumpy proprietor.

Into a much larger economic conversation

News of the sale to a local developer of multimillion-dollar vacation homes and luxury apartments couldn’t help but thrust the campground project into the long-simmering debate about the economic evolution of the southern Berkshires. With skyrocketing housing costs and related growth in high-end amenities, if trends continue, who will be able to afford to live, work, and vacation here? Is the region destined to become an expensive, Hamptons-like enclave? Is it a version of that already?

Those questions, and Egremont’s economic and demographic trajectory, have been very much on the minds of those in the community of fewer than fourteen-hundred residents, along with its part-time weekend-home owners.

By 2040, Egremont’s full-time population is projected to decline from today’s 1,400 residents to approximately 753.

In Egremont and across the region, businesses continue to struggle to attract and retain employees, and families with children are departing for less expensive locales—often because of unmanageable housing costs. Egremont’s population trends are also worrying: A 2021 housing-needs assessment prepared for the town by the Berkshire Regional Planning Commission projects a forty-six percent population decline by 2040, to just 753 full-time residents, based on a University of Massachusetts analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. And the number of residents aged 0-19—relevant when considering the defeat last month of a proposal to combine two local school districts, with Egremont voting 143-78 against the merger—is projected to shrink by fifty-five percent, to just 120.

It was within that context that a year-long process to update Egremont’s comprehensive plan—and craft ideas to preserve open space and enhance recreational opportunities—began last year in late summer. It attracted substantial community interest and engagement: More than three hundred fifty detailed surveys were completed and Zoom committee sessions were well-attended. There were also facilitated, in-person gatherings: At a lively community meeting held on cold Saturday morning in January, more than a hundred people met to share ideas and rank priorities as part of what was dubbed “Egremont Vision 2035.” (A second in-person public meeting was held in March.)

Topping the priority list was the need for affordable and workforce housing, which was no surprise: It’s expensive to live in Egremont. Driven by forces that only accelerated during the pandemic, housing prices have more than doubled since 2012, with the average residential property value edging north of $800,000. Nearly a quarter of Egremont families now earn more than $200,000 per year, according to 2021 census data.

Egremont resident Charles Miller, who is principal at the school district’s elementary school, highlighted the facts-on-the-ground during a public Zoom meeting last winter and again at the community’s annual-town meeting in May. He said six young families had recently departed because of housing costs in Egremont and the district’s other four towns. The issue is making it hard to attract and retain teachers and staff, Miller told voters.

In response, the town’s Housing Committee and its newly formed Municipal Housing Trust—the latter chaired by another Egremont real-estate developer, Richard Stanley—have kick-started long-stalled efforts to address the housing-cost challenge. While the new trust aims to fund construction of new units, the Housing Committee is working to address substantial growth in properties dedicated to short-term rentals—and their impact on housing availability and cost. (According to state and town data, there are currently seventy-seven registered short-term rentals in Egremont; only eight are owner-occupied.)

Other priorities highlighted during the winter visioning sessions include protecting the town’s rural character, maintaining a lively South Egremont town center, preserving historic buildings, developing community gathering places, and—relevant to the project underway at the former campground property—expanding public access to the fifty-eight-acre Prospect Lake.

The importance to residents of improving lake access can’t be overstated: The surveys last winter produced more than seventy-five written comments about it—some ending with multiple exclamation points. “Current access to Prospect Lake for Egremont residents is nearly nonexistent. This is a travesty,” one wrote. Further, two of the top three recommendations for recreation-related spending were “canoe and kayak access” and “outdoor swimming,” respectively. (Topping them both was a wish for more pedestrian and hiking trails.)

What’s the actual plan for the campground property?

While Rasch’s new business has been vaguely understood to be some flavor of upscale “glamping,” short for “glamorous camping,” complete details have never been formally shared with residents or town boards. Mary Brazie, who has been Egremont’s town-office administrator for all but six months of the last four decades, and a Select Board member from 2002-2008 and 2012 to the present, told me in late summer that she, too, doesn’t know what to expect. “I guess I’m waiting to see,” she said. “The Select Board hasn’t officially seen what Ian has planned for it. So it would be speculation on my part to make an opinion because I haven’t seen anything.”

(Rasch declined multiple requests to be interviewed for this story.)

“Current access to Prospect Lake for Egremont residents is nearly nonexistent. This is a travesty.”

—Comment in a Town of Egremont survey

Asked to provide an update for an October, 2022, town newsletter, Rasch continued to keep the full project scope close-to-the-vest. He described general plans for “recovery of the site ecology,” renovations to some historic buildings, and removal of other structures. (To date, at least sixteen buildings have been demolished.) Rasch, who lives in Egremont, told his neighbors, “The campground will continue to operate as a campground but with fewer sites and upgraded amenities,” and promised “a limited number of dedicated parking spaces for Egremont residents”—something town officials have long sought as a component of that improved lake access residents desperately want.

All evidence is that Alander Group is indeed making a sizable investment to upgrade the amenities: Last month, Rasch’s 50 Prospect Lake LLC secured a nearly $12 million loan from Adams Community Bank, according to mortgage documents filed with the Southern Berkshire Register of Deeds.

And while he still refers to the property as a “camp” or “campground”—cognizant, no doubt, of its preexisting nonconforming zoning status, with limits that bubbled up to the town’s Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) in May and with new intensity again this week—what he’s spending handsomely to create is called a “landscape hotel.” That’s according to information posted online [PDF] by multiple architects and consultants working on the project, documents and information conveyed by Alander Group to town boards in both Egremont and Great Barrington, and the limited details Rasch has shared since the purchase.

An emerging trend in upscale hospitality

Marketed to affluent city-dwellers seeking escape, landscape hotels promise a peaceful-and-restorative excursion into nature, typically in minimalist cabins accompanied by luxury amenities. Pioneered more than a decade ago by Norway’s Juvet Landscape Hotel—featured earlier this year in an episode of the HBO series “Succession”—it’s a type of hospitality venture known for creative architecture and design that puts natural surroundings front and center.

Garrison Architects, the Brooklyn-based firm that last year won several awards for its work on Piaule Catskills, a landscape hotel southwest of Hudson, New York, also designed the cabins that have recently begun to dot the former campground property in Egremont. Image renderings and a video called “Prospect Lake” were posted online by Garrison in June, 2022, and suggest how a portion of the new lakeside resort may look when complete.

A 2022 video presenting a vision for the landscape hotel at Prospect Lake. (gansandco.com)

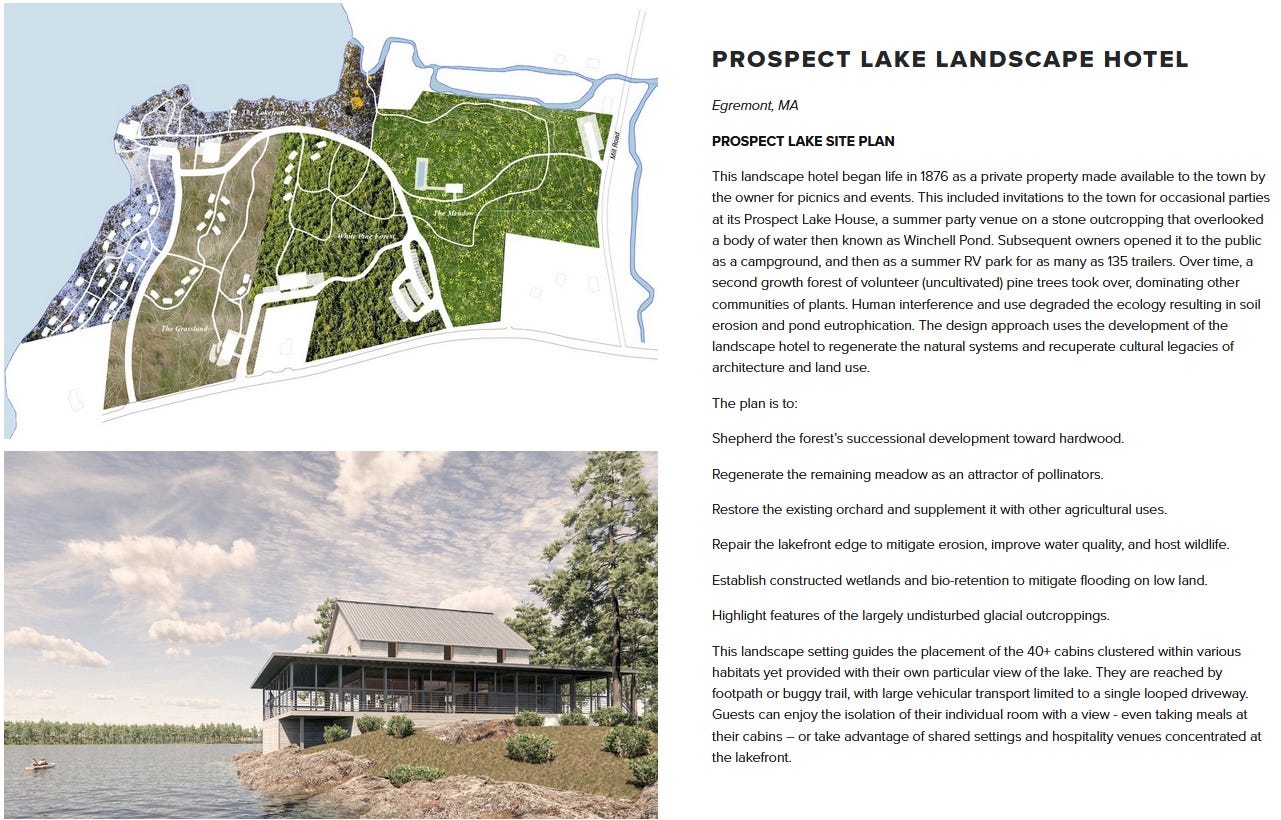

A more detailed project narrative, including images that were shared with the ZBA, was posted online earlier this year by Brooklyn’s Gans and Company, an architecture and design firm helping guide the project. Describing the “Prospect Lake Landscape Hotel,” it begins, “This landscape hotel began life in 1876 as a private property made available to the town by the owner for picnics and events.” Over the years, it explained, the property became a campground and RV park, but “human interference and use degraded the ecology.”

The “design approach uses the development of the landscape hotel to regenerate the natural systems and recuperate cultural legacies of architecture and land use,” according to the narrative. That’s led to substantial ecological-restoration work on the property that has, so far, included removal of more than 200 trees—at least some already dead or dying—and plans to replace the campground’s beach areas with “restored wetlands.” That means, as Rasch told me last year, access to the water for swimming will be via existing piers; there will be “no direct swimming areas,” as he told the Egremont Conservation Commission in July, 2022.

“The design approach uses the development of the landscape hotel to regenerate the natural systems and recuperate cultural legacies of architecture and land use.”

—Gans and Company description of the “Prospect Lake Landscape Hotel”

Over the past eighteen months, the Conservation Commission has granted multiple approvals for tree removal, earthworks, plantings of native species, and other work at the water’s edge. Rasch’s methodical approach and his ambitious ecological plan have been praised by members of several town boards who often note the environmental work is voluntary. That’s compared to remediation sometimes ordered by the Conservation Commission in the wake of unauthorized construction or landscaping that’s done in wetlands or other regulated areas.

Voluntary or not, it’s central to the venture: “This landscape setting guides the placement of the 40+ cabins clustered within various habitats yet provided with their own particular view of the lake,” according to the Gans and Company description. “Guests can enjoy the isolation of their individual room with a view—even taking meals at their cabins—or take advantage of shared settings and hospitality venues concentrated at the lakefront,” the narrative notes.

Historic images of the Cliff House, renderings presented to the ZBA, and the building as it appeared in mid-November. (Historic: via Gary Leveille, Renderings: Egremont ZBA, Construction: Bill Shein/Berkshire Argus)

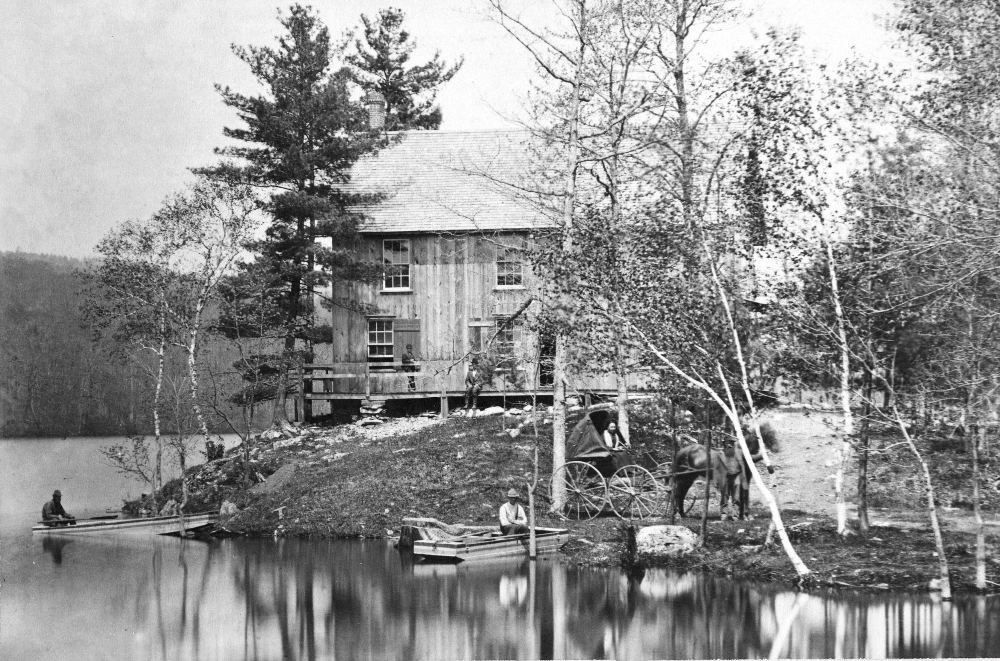

At least two historic buildings on the property, called the Cliff House and Rec Hall barn, have already been stripped down almost entirely to “expose the original heavy timber chestnut frame[s]” and will, according to Cliff House plans filed with a building-permit application, be re-imagined with a refreshed look. (The original Cliff House dates to 1876 and has gone through almost countless additions and revisions.)

The various buildings’ design will, the description states, “echo both the industrial vernacular of the local mills and the clapboard tradition of the region.” (Work on the Cliff House alone will cost nearly $900,000, according to the building permit.)

The renovated Rec Hall barn—also labeled “Spa” on some documents filed with the town—will be used by hotel guests for various activities, as it has over the long history of the former campground: “The building will serve as a multi-function space for the hotel, suitable for yoga classes, rainy day activities and catered events,” the project managers wrote.

Renderings of the Rec Hall barn, which will be remade but reportedly retain its footprint and height. (Egremont ZBA)

Also described is “The Market,” shown on plans as a new building and retail business located immediately off Prospect Lake Road that will serve as “the public facing signature for the Prospect Lake Landscape Hotel in the woods behind it … Its goods serve both the local community and hotel guests, who can reach it via woodland trails from the resort without crossing a road,” the description says.

But that retail component may be in doubt: Rasch told the ZBA this week that the only new structures planned for the property are a pool and adjacent pool-house. “The scope is 100-percent set now,” he said. “We’re not going to come back and look to build anything else.”

Renderings of "The Market," a new business that would serve both hotel guests and be open to the public. (gansandco.com)

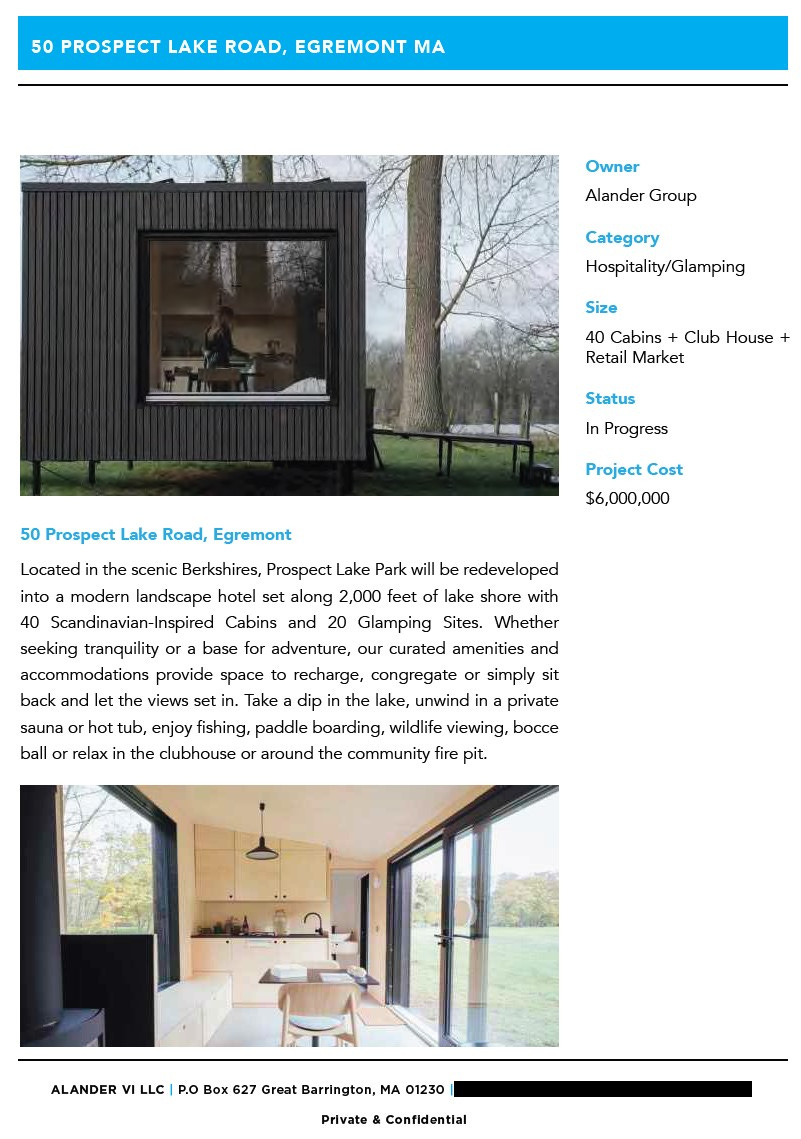

Some of these details were hiding in plain sight. Last December, in an unsuccessful application for funds from the town of Great Barrington to help underwrite affordable-housing units in Alander Group’s two downtown projects there, the project in Egremont was called “a modern landscape hotel.” It was described as a six-million-dollar redevelopment featuring “40 Cabins + Club House + Retail Market,” curated amenities like private saunas and hot tubs, and the possibility of twenty additional seasonal glamping tents.

Similar to a landscape hotel in Hudson, New York

The as-yet-unnamed venture is strikingly similar to Piaule Catskills—not surprisingly, given that Garrison Architects designed the cabins at both. That popular year-round resort, which opened in 2021, offers spare, “luxury modernist cabins” that are, according to its website, “nestled into the forest or open to the sky, enveloped by the healing power of the earth.”

That healing power doesn’t come cheap: Nightly rates for single cabins start at $499 plus taxes and resort fees. Like other landscape hotels, Piaule Catskills also provides on-site amenities including $250-per-hour massage, activities like “forest bathing” walks, and a restaurant. (Rasch told the ZBA he plans to offer only a continental breakfast in the Cliff House, where, many years ago, there was a snack bar. The Gans and Company description noted, too, that cocktails will be served there every night. “You cannot have a hospitality-based venture today without providing some level of food,” Rasch told the ZBA in May.)

But Piaule Catskills is not for families with noisy toddlers or boisterous teenagers in tow. Its website FAQ says, “Due to the tranquil nature of the Piaule experience and lack of recreational options, we discourage bringing children between the ages of 2 and 18.”

There’s certainly a robust market for this type of high-end nature retreat, both in the Berkshires and elsewhere. CondeNast Traveler magazine, a guide to high-end global travel, selected Piaule Catskills as one of its top hotels last year, praising its “stylish escapism” that “feels like a designer cabin in the woods.” It judged the nightly rates not only “reasonable,” but suggested that “for the way it makes you feel (and the effort involved in its design) it should cost way more.”

At a price point like that, it’s not hard to understand why the new Egremont resort won’t offer traditional campsites or utility hook-ups for those who formerly arrived at the Prospect Lake Park campground with tents, driving their own RVs, or towing pop-up campers. As reported last year, it seeks to stay within its current zoning limits via a regulatory exemption, first established in 1982 by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), that allows cabins of up to four hundred square feet to be considered RVs—but only if they are mounted permanently on a chassis with wheels and comply with a construction standard known as ANSI A119.5–15. That building code is less strict than HUD rules for manufactured housing, like mobile homes, that are used for year-round living—but there are still life-and-safety requirements to be met.

Called “park model RVs,” there’s no requirement that they ever travel on a roadway, and few would mistake them for a vehicle or traditional camping trailer. Indeed, many are too wide to be towed directly on highways without what’s known as a “special-highway-movement permit.” Once in place, each is connected to water, sewer, and electric service like a traditional RV camper.

Jeff Sims, a longtime industry lobbyist with OHI (formerly the National Association of RV Parks and Campgrounds), told me recently that park model RVs can even be constructed at the location where they’ll be permanently sited without running afoul of federal rules. (A regulatory change in 2018 removed the phrase “factory built” from HUD’s definition of park-model RV.)

Industry groups like OHI and the RV Industry Association (RVIA) have fiercely protected that regulatory exemption. As Sims told me last year, the industry sees park model RVs—at least in the context of traditional RV parks and campgrounds, where park models are a small-if-rapidly-growing market segment—as an important offering. “What it does,” he said, “is provide an opportunity for someone that doesn’t have a recreational vehicle to still enjoy the atmosphere and ambiance of an RV park without the investment.”

One of the larger campground operations in Massachusetts, Yogi Bear’s Jellystone Cranberry Acres, in the town of Carver, this year added eighty-three park-model RVs to its mix of RV sites and traditional campsites. Mounted on the required chassis-with-wheels, they’re offered as “cabins” on its website, highlighting the ongoing regulatory and rhetorical gray area that park models occupy. Indeed, that resort’s park-model cabins include sleeping lofts, large decks, full bathrooms, and a small kitchen.

“They’re not going to be permanent, because they’re on wheels.”

—Cynthia Zbierski, Massachusetts Association of Campground Owners

Since they’ll be new to Egremont, local officials will need to determine what type of health-and-safety inspections and other permitting they might require. That appears to be underway: Juliette Haas, director of the town’s Board of Health, briefed its members at a February meeting, explaining that based on what she understood about Rasch’s plans, there would likely be additional inspections required.

“What they’re going to be, as opposed to what they were, is going to be so vastly different,” Haas told the board about the difference between the old and new enterprises on the former campground’s property. “I’m thinking this is going to turn into a lodging,” she said, noting plans for forty “glamping-type units” that she described as “similar to a guest house except it’s not a guest house. They’re like little wagons.” In effect, she said, the Board of Health will likely perform inspections like those it did at Egremont’s former Weathervane Inn or the prior Egremont Inn, where rooms were inspected annually.

Overall, Haas and the board seemed to be puzzling out what it would mean for their work. “It could be a ‘campground,’” Haas said, making air-quotes with her hands, “but it will be a campground in name only.” While the board agreed that was largely a zoning question outside their purview, the chairperson, Charles Ogden, said, “It almost sounds like a change of use.”

When I spoke to Haas this week, she confirmed the various inspections performed and permits typically issued at the former campground: Examining bath houses and a food prep area, and licenses for garbage hauling, a semi-public beach, and a campground. Regardless of what form the new venture takes, she told me the Board of Health will provide oversight of the accommodations. “It’s premature at this point,” she said, “but whether they’re on wheels or not, there will be a mechanism to inspect them, whether it’s considered lodging or whatever code it falls under.”

Cynthia Zbierski, president and CEO of the Massachusetts Association of Campground Owners (MACO)—and an energetic advocate for fifty-five of the Commonwealth’s roughly seventy-five campgrounds and RV parks—told me that in Massachusetts, park-model RV’s are registered with the Registry of Motor Vehicles. Her organization works with local boards to help them understand the full range of campground operations, including compliance with health-and-safety requirements for “family-type campgrounds” enshrined in state regulations. And to explain how park-model RVs fit into the mix across the Commonwealth.

“Whether they’re on wheels or not, there will be a mechanism to inspect them, whether it’s considered lodging or whatever code it falls under.”

—Juliette Haas, director, Egremont Board of Health

“That’s everything from an eight-site campground to a 450-site campground,” she said, describing MACO’s work to educate campground owners on, for example, life-safety guidance issued by the National Fire Protection Association.

Like Sims, Zbierski wouldn’t concede that most park-model RVs are, for all intents and purposes, never going to be moved. And certainly not like a conventional RV. When I asked if, as a result of being permanently sited, they might require a closer look by local authorities, she stopped me short and delivered the party line. “They’re not going to be permanent,” she said, “because they’re on wheels.” (Zbierski said she knew about the sale of the former campground but was unfamiliar with any plans.)

Threading a zoning needle—with some rapidly growing turbulence

But it wasn’t plans to install forty or more park-model-RV cabins on the property that landed Rasch, his longtime business partner Roman Montano, and their attorney in front of Egremont’s zoning-appeals board in mid-May. Instead, they were there because the town’s building inspector, Ned Baldwin, had denied a building-permit application for the substantial remaking of the Cliff House.

In a March 2 letter to Montano, Baldwin wrote, “The application to build the ‘Cliff House’ for commercial use in a residential zone does not contain supporting documents showing that this is a similar commercial endeavor to what was in existence previously.”

Montano’s filing with Baldwin didn’t explain the property’s long use as a commercial campground or describe how the new Cliff House would be used. (Historian Gary Leveille’s 2011 deeply researched book about North Egremont and Prospect Lake, “Eye of Shawenon,” chronicles the campground’s long history in extensive detail.)

That information is relevant: Egremont’s first zoning bylaw went into effect in January, 1967—long after a campground was established. So, the two-parcel property’s preexisting nonconforming status means that no zoning-related approvals are required from the Planning Board or ZBA as long as the commercial use, as a campground, isn’t substantially altered or expanded. The specific meaning of crucial words like “alteration,” “change,” “extension,” and “expansion” are guided by the town’s zoning bylaw, state statutes, and case law that provides well-established evaluation criteria—all of which seems, at times, to be designed to help land-use attorneys meet billable-hour targets.

On May 15, at the end of a forty-five-minute public hearing, the ZBA unanimously overruled Baldwin’s denial and ordered a permit for the Cliff House renovation be issued. But not before the board’s chairperson raised broader concerns—and information came to light—that suggest the project is likely to need further approvals.

Rasch’s attorney, Peter Puciloski of Great Barrington’s Lazan Glover & Puciloski—a firm specializing in real-estate law—argued during the hearing that there was “adequate evidence that the Cliff House was used as part of the campground operation,” and therefore Baldwin had no reason to deny the building permit. He pointed to excerpts from Leveille’s book and descriptions of Cliff House activities over the years, including that, at one point, it housed a snack bar. And he cited court decisions that, he said, mean it doesn’t matter where various campground activities took place; they can continue anywhere on the property and in any building.

(By all accounts, for the last twenty-five years the Cliff House served as the year-round personal residence of the campground owner. From at least 2012, the campground’s site map labeled it “private home,” as did a campground schematic attached to a 1998 building permit for construction of a pole barn.)

“The application to build the ‘Cliff House’ for commercial use in a residential zone does not contain supporting documents showing that this is a similar commercial endeavor to what was in existence previously.”

—From a March 2nd letter to Alander Group from Building Inspector Ned Baldwin

Perhaps aiming to preempt any future zoning headwinds, Puciloski went beyond the question of the Cliff House building permit, as he did in an earlier response he sent to Baldwin. Compared to the former Prospect Lake Park campground, he said, the new venture will reduce the detrimental impact of a commercial enterprise operating in a residential area. That’s among the key considerations when evaluating whether a preexisting nonconforming use has been altered, changed, or expanded in a way that bumps into its zoning limits.

Notwithstanding the park-model-RV exemption, Puciloski made another claim that may rest on shakier ground—rhetorically, at least, but perhaps also as to zoning limits. “What we’re proposing is the same in kind and nature as the previous camp,” he said, using language drawn from the so-called “Powers test” established by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in a 1978 decision on preexisting nonconforming uses.

And while he conceded there will be “alteration in the scope of use,” he said it’s only to the better: A planned fifty-two percent reduction in the number of available guest sites, from one hundred twenty-five to a maximum of sixty, will “significantly reduce” the number of people on the property, Puciloski said, cutting down on noise, traffic, and light pollution.

He also highlighted aesthetic improvements like the removal of “forty-year-old trailers,” the substantial ecological-restoration work already underway, and the installation of “custom-built trailers to Ian’s specifications.” (In the appeal filing, these were labeled “cabins.”) All of that should, he suggested, take questions about the project’s zoning status off the table.

Puciloski concluded his reduction-of-impact argument with a striking inference about those who frequented the former campground—one sure to further rankle the already-rankled. “Not only will the population be significantly reduced,” he told the board’s three members, “we believe it’s going to attract a different clientele than the prior operation.” There was no reaction from board members; none asked Puciloski what that meant.

Unprompted by any question from the board, Puciloski also sought to protect against future claims that the campground use may be considered “abandoned” if it doesn’t reopen for business within two years of the January, 2022, sale to Rasch. That’s because under the town’s zoning bylaw, a legal nonconforming use that has not been used for two years, or more, may not be “re-established” without a special permit from the ZBA. “The final trailers were not removed until August, 2022,” Puciloski said, “so we say the two years for renewal begins [then] and not at the purchase.”

“Not only will the population be significantly reduced, we believe it’s going to attract a different clientele than the prior operation.”

—Great Barrington attorney Peter Puciloski, describing reduced neighborhood impact.

Fred Gordon, the ZBA chair and a town resident since 2017, listened closely to the presentations. And he said he had reviewed relevant case law. But he was still concerned about the lack of project details. He didn’t know what might happen at the Cliff House in the future and was “concerned about unconstrained entertainment”—he asked about plans for music concerts—that could impact those living around Prospect Lake. “Sound travels on the lake,” he said.

“I do see this as a commercial property, it’s always been a commercial property,” Gordon explained. “But I don’t feel as if I have the proof that the commercial endeavor will be similar to what it was.” (Neither Puciloski nor Rasch used the phrase “landscape hotel” during the hearing. At one point, Rasch called it a “nature-based hospitality project.”)

Rasch told Gordon there were music concerts and other events at the campground in the past, and said that his overall plan would reduce noise, light, and the intensity of use, as his attorney described. He said he’s open to more detailed conversations about those issues—but in the future. “I understand your concerns,” he told Gordon, “but I don’t want to reduce the limits on what we can do there arbitrarily.” (Brazie, the longtime town employee and Select Board member, told me this month that she didn’t recall any entertainment licenses issued to the former campground over the last decade.)

Puciloski sought to assure the board that the conversation will continue. “We’re going to address any issues that the abutters or the board has,” he said.

Lucinda Fenn-Vermeulen, a local real-estate agent, former owner of the skiing-and-sporting-goods store Kenver, Ltd., in South Egremont, and a Select Board member since 2019, also spoke at the hearing. She noted that no public comments had been submitted and no residents asked to speak either for, or against, the building permit. “I just want to point out that this notice of a public hearing with the ZBA has been public since April 25, and there is not a single abutter speaking,” she said. “I would suggest that that’s an answer worth listening to.”

(Fenn-Vermeulen, who has attended, via Zoom, many town-board meetings this year where the former campground was discussed, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

In the end, the other board members, Rolfe Tessem and Mark Holmes, convinced Gordon the only issue was whether the Cliff House could be renovated. The question of whether the new enterprise might require further zoning approvals was not currently on the table, Tessem argued. “I’m not clear that this should have ever gotten to the ZBA to begin with,” he said. “[These are] subjects for another venue.”

Rasch quickly agreed. “I don’t think the entire preexisting nonconforming use is up for discussion,” he told the board. “Whatever happened before on the site theoretically can continue to happen as long as it’s not more detrimental to the community and abutters.”

A sharply worded attorney’s letter—and continuing missing details

While that’s almost certainly an oversimplification, the question of whether the full extent of the planned landscape hotel’s buildings and activities is the same use, under zoning laws, as the prior campground-and-RV park, may still need to be formally ratified with a full special-permit application reviewed by the ZBA.

And, indeed, that ultimate destination may be coming into view: A few weeks ago, Baldwin, the building inspector, once again raised red flags about proposed work at the property that he believed needed ZBA approval. This time it was for renovation of the Rec Hall barn and construction of a new pool and adjacent pool-house. (The pool and pool-house are shown in the Gans and Company landscape hotel site map, but were never displayed, over the last 18 months, on plans shown to members of the Conservation Commission or ZBA.)

While being allowed to add a pool or pool-house “by right,” as Rasch’s attorneys say is allowed, may seem modest, it highlights still-unresolved zoning questions and the broader information vacuum within which Egremont town boards are making decisions about one of the largest, most expensive hospitality projects seen in Egremont in some time—and one directly connected to residents’ quest for meaningful access to Prospect Lake.

Made aware of his reluctance to issue the building permits, Puciloski fired off a letter [PDF] to Baldwin arguing the ZBA’s Cliff House decision “accepted the argument that the entire premises were to be considered as historically part of the Campground activities.” He concluded with language suggesting an imminent, but nonspecific, escalation: “Your continued refusal to issue building permits to which the Campground is entitled will have serious consequences for the town.” (The letter was acquired by the Argus in a public-records request.)

That threatening language certainly got the town’s attention. The ZBA held an hour-long discussion on the matter on Tuesday afternoon this week that included Town Counsel Jeremia Pollard, Montano, Rasch, and another Alander attorney, Alexandra Glover from Lazan Glover & Puciloski.

“Your continued refusal to issue building permits to which the Campground is entitled will have serious consequences for the town.”

—Attorney Peter Puciloski, in a November 15th letter to Egremont Building Inspector Ned Baldwin

As he opened the meeting, Gordon said its purpose was to help Pollard and Puciloski—who have exchanged correspondence [PDF] in which they disagreed on the need for any further zoning approvals—to understand the scope of the board’s crucial May decision on the Cliff House.

That written ZBA order [PDF] provided scant details of the board’s discussion or the specific basis on which it reached its conclusions. Other than referencing application of the legal test used to evaluate the impact of an alteration or expansion of use, it included no details of its fact-finding or rationale in the legal record. Gordon said the meeting would “help the attorneys get inside our heads to know more about the criteria we used to arrive at that decision, and the scope of that decision.”

Rasch and Glover both argued that because any alterations to the former campground will purportedly reduce the intensity of use, and they say it will remain a recreational venue, they shouldn’t need any more ZBA approvals beyond the Cliff House decision—even to build new recreation-related facilities like a pool or structures like a pool-house.

That argument went nowhere with Pollard. He focused instead on the lack of project details and the inability, without them, to address key questions of alteration, change, or expansion. “What’s the overall project? That’s the million-dollar question,” he said. “What we need is to actually have the plans, and what is going to be built, and then you decide: Is it by-right or does it require a special permit?”

Baldwin agreed. A lot of this confusion “could have been avoided,” he said, if the board had been provided with a plan showing all features of the planned venture. “Usually, people bring a site plan with all the buildings that are going to be done, all the work that’s going to be done, and then the ZBA approves or disapproves in its entirety,” he explained.

Required submissions to the Egremont ZBA as part of a zoning appeal include, according to the town’s instructions, a site map that displays “all existing structures” and “all proposed new construction.” The site maps provided by Alander Group showed only the former campground’s layout and buildings, including many that were already demolished. There was no pool or pool-house displayed, something Gordon pointed out: “We had two existing site plans,” he said of documents presented at the May hearing. “We did not have a complete site plan for the complete project.”

“What’s the overall project? That’s the million-dollar question.”

—Egremont Town Counsel Jeremia Pollard

Technically, the appeal was only related to one proposed construction project: Renovation of a single building. No other building permits were pending at that moment, so a site plan showing them was not provided. But the possibility that Rasch’s piecemeal approach was obscuring a change of use appeared to be Pollard’s concern—especially as Puciloski argued the ZBA’s Cliff House decision was all that was needed to allow any additional new construction.

Tessem, in particular, dismissed concerns about absent project details, suggesting there were plenty of conversations—including during a site visit and at other times—about what is planned for the property. He said he didn’t want to stand in the way of the project and seemed to disagree with his own town counsel—an unusual position for a volunteer-board member.

“I just want to be clear that the Select Board has been heavily involved in this project,” Tessem said. “The Conservation Commission has been involved in various aspects of it. This is a big project and has been well known to all the relevant regulatory bodies the town has. So, it’s not like any of this is a surprise to anybody.”

But Pollard, who serves as town counsel for eleven western-Massachusetts municipalities—and is surely aware that volunteer boards can inadvertently lay potentially expensive legal land mines—was far more cautious. He pointed to several years of legal action after, in 2009, the town too hastily allowed Catamount, the ski resort that straddles Egremont and Hillsdale, New York, to add a five-acre aerial adventure park without even requiring a building permit, much less a special permit that allowed expansion of its preexisting nonconforming recreational use. (Pollard conceded that he helped to make that initial erroneous decision; it started with an abutter’s complaint and ended, years later, with a special permit issued and then upheld in court.)

“There is no way that you’re going to hear from me—set this project aside—[that] as a general proposition, if someone establishes a preexisting nonconforming use, that they can [then] build whatever they want, as long as it’s within that use,” he said.

Pollard continued, “If that were the case, you could just take a pen and just write a line right through the portion of Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 40A, Section Six and our zoning bylaw.” He pointed to legal language whose intent, he said, is that “if you alter, not just expand,” a preexisting nonconforming use, “you go and get a special permit.”

ZBA member Holmes, for his part, noted that the proposed pool and pool-house were both new to the property; Pollard had suggested that qualifies as an “alteration,” even if it’s still a recreational use. “The scope of our [May] decision was pretty narrow,” Holmes said, suggesting the pool projects would need a separate board approval.

In the end, Gordon, the board chair, was measured. “I want everyone to think about what each of us can do to expedite the completion of the pool-house and the pool, if we think it’s the right thing to do,” he said. “Because I personally do want to move this project forward as quickly as possible, but do it the right way.”

(By Thursday, Baldwin had issued a building permit [PDF] for construction of the $200,000 pool, at least, according to a copy obtained by the Argus in a public-records request.)

The meeting, which was open to the public via Zoom but appeared to have no outside attendees other than Fenn-Vermeulen and Planning Board member Mary McGurn, ended inconclusively. The conversation was generally cordial, but there were moments of heightened tension: Rasch’s response to the possibility of needing broader approval, via a special permit, didn’t quite reach a level of exasperation, but he was clearly frustrated. That’s part of the job, he told me last year: He’s used to working through zoning and other issues that come up as large projects proceed. “I love what I do,” he said last October. “But none of these are easy. They seem to get harder as time goes on.”

“I personally do want to move this project forward as quickly as possible, but do it the right way.”

—Egremont Zoning Board of Appeals Chair Fred Gordon

Despite the meeting’s extended focus on gaps in information about Rasch’s overall plan, the phrase “landscape hotel” was never uttered. Whether that term is rhetorically unimportant, or, alternately, fundamental to enabling residents and town boards to understand the property’s proposed use, was not explored.

More approvals still to come

At minimum, various operating permits and board approvals will be required, including to serve alcohol—via a new liquor license issued by the Select Board—and for any substantial food-service operation beyond what existed at the former campground. (In July, Rasch established a new Massachusetts entity called F&B @ Prospect Lake LLC to “prepare and sell food and alcoholic beverages,” according to a state filing.)

A special permit would almost certainly be needed to allow the retail market described in the Gans and Company project description, and for any move to extended or year-round operation. Last year, when I asked Rasch about keeping the new venture open year-round, he said, “We’re looking at that,” but that it was “unlikely.” Still, he noted opportunities for activities like ice skating and ice fishing on the lake, and perhaps other opportunities for winter programming at the property. Given the substantial investment, it seems plausible he’ll want to operate the landscape hotel for more than just five months a year: During 2021, its last year in operation, Prospect Lake Park campground was only open from May 7 to October 15.

“I love what I do. But none of these [projects] are easy. They seem to get harder as time goes on.”

—Alander Group’s Ian Rasch, October 2022

When I spoke a few months ago to Gordon, the ZBA chair—who retired eight years ago from a career in institutional finance—he told me that his priority as a board member is to maintain the balance of residential and business uses in town. He said that during the May hearing he probed for more information to make sure he understood what a vote to overturn the building inspector could mean.

“I was poking around, trying to get a sense of, okay, that’s what we’re talking about today,” he said, “but what’s the long-term vision?” Gordon said he worried that unannounced plans might “potentially [have] a different effect on the neighborhood.” (During the May hearing, he was explicit: “I do worry about that—that it can turn into something we may not like. We may unleash something that we wouldn’t normally approve,” he said.)

Gordon conceded that his queries might have been premature, given what was in front of the board. “I think I was getting ahead of myself in [trying to get] some answers” about the project, he said. “But they weren’t very forthcoming—and that’s understandable.” He said needed approvals for things like a liquor license, or permits for music and entertainment, will present town boards additional opportunities to review the venture.

But given what came roaring back to the ZBA this month, and the new threatening language from Alander Group’s attorney, Gordon may have been prescient: The concern he expressed in the spring about missing project details was at the heart of Tuesday afternoon’s discussion, where he was joined by Pollard and Baldwin in asking, essentially: Why is it so hard to get a full, complete picture of the end point of this important project?

It may be that various town officials have incorrectly assumed that others know more: Tessem suggested as much, saying at Tuesday’s ZBA meeting that the Select Board and Conservation Commission were “heavily involved in this project.” Back in August, Gordon, too, said that he assumed more information had been shared with the town. “My suspicion is that [Rasch] has had conversations with the Select Board,” he told me, “but I don’t know for a fact what his ultimate plans are.”

Nearby challenges to upscale glamping and RV park proposals

Egremont’s is not the only campground-related venture in the region drawing both interest and scrutiny. Far larger Berkshire County proposals, like one for a three-hundred-site RV campground at an overnight summer camp in Hinsdale, and a new, one-hundred-site, cabins-and-glamping-tents plan for the property of the storied Dreamaway Lodge in Becket, were both scuttled last year by neighbor opposition and town-board denials. (In both cases, the debate included arguments—sometimes heated—over the definition of “camping.”)

Also in north county, a proposal for the long-delayed Greylock Glen campground in Adams, being developed by Shared Estates—another Berkshires-based, private-equity-backed, high-end developer—quickly ran into complaints about nineteen luxury “mirror cabins” in its so-called “EcoVillage” that environmentalists warned posed a significant threat to birds. Some Adams residents also argued the glass cabins were out-of-character for a rustic outdoor retreat in their community.

The addition of an RV park to Hume New England, an evangelical Christian campground in Monterey, was allowed to proceed after the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled it was “religiously significant.”

After insisting those specific cabins were integral to the economics of the project, Shared Estates eliminated them, reworked its plan, and sought to allay concerns by hosting a public-input session last spring attended by hundreds of residents. (A lease agreement with the town of Adams is still pending after numerous delays.)

In the southern Berkshires, the addition of an RV park to Hume New England, an evangelical Christian campground in Monterey, was allowed to proceed after the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled its “camping ministry” was “religiously significant” and could therefore bypass a town board’s rejection of the plan.

And across the state line, last year a Getaway House project that proposed thirty-eight cabins-on-trailers on ninety acres in the woods of Claverack, New York, was rejected by a town board after neighbors complained it was more like a permanent hotel than a seasonal campground. And a ferocious, two-year battle in Ancram—a rural Columbia County town of fifteen-hundred residents—ended last December when a developer appeared to abandon plans to build a high-end glamping resort on one hundred forty-seven acres. It aimed to “host guests who search for luxury unpretentious adventures close to home,” according to promotional materials.

Other nearby glamping ventures are thriving, boosted in part by pandemic-era vacation trends. But they’re typically far more modest. That includes The STAY at Liberty Farms, in Ghent, New York, where ten familiar-looking canvas tent-cabins start at around two hundred dollars per night. And Gatherwild Ranch, where eight cabins and well-appointed canvas-tent accommodations are set in the woods of Germantown, New York, among farm animals and gardens, includes guest amenities like a shared outdoor kitchen and bathhouse. Piaule Catskills, the nearby landscape hotel, has twenty-four single-and-double cabins on fifty acres.

A lot of zoning smoke but ultimately no fire?

Andy Zipser, the former Wall Street Journal reporter who, in retirement, owned a Shenandoah Valley RV park and now writes extensively about the camping industry, told me that Rasch’s project is not likely to run into the same problems encountered by those other developers. Among the reasons, he suggested, is that the Egremont venture is in an existing commercial location, and the plans are—as Rasch and Puciloski argued in front of the ZBA—quite likely to reduce traffic and other neighborhood impacts.

Projects that run into trouble, like those that failed in Hinsdale and Becket, often propose something large and entirely new. “Some are like dropping a big boulder in a small pond,” Zipser said. “[But] this is a preexisting use. Basically, in terms of camping, it’s a different use, but it probably is, in fact, less impactful than having people pulling in every day with their RVs.”

“It’s a lot simpler to come in under old zoning regulations that never contemplated that ‘camping’ would be interpreted this way.”

—Andy Zipser, author of “Renting Dirt: An Unfertilized Look at What it Takes to Run a Campground and RV Park”

So it could be that a special permit allowing for change or expansion—or even a brand-new special permit from the Planning Board for a landscape hotel unconstrained by the limits of its preexisting nonconforming status—will face little resistance from residents or town boards. While he was careful not to forecast any outcome, that seems to be what Pollard, the town’s attorney, was hinting would be the most prudent path for both Rasch and the town—at least to protect against any future legal squabbles.

Still, Zipser, a close observer of industry trends, remains critical of how park-model RVs—the central element of the new landscape hotel—can squeeze through regulatory loopholes. (He’s dubbed it “the park-model scam.”) Across the country, that’s allowed developers to take advantage of communities that lack specific campground-related regulations. “Part of the reason Rasch is doing it this way,” Zipser told me recently, “is that it’s a lot simpler to come in under old zoning regulations that never contemplated that ‘camping’ would be interpreted this way.”

As Zipser wrote about Prospect Lake last year, “[Rasch] can maintain the fiction that the property will remain what it’s always been: a ‘campground.’ Just don’t try to camp there.”

∎ ∎ ∎

NEXT: In the second part of this two-part series, an update on efforts to repair the Prospect Lake Dam; details of an agreement to provide limited parking and lake access for Egremont residents at the landscape hotel, and the possibility of substantial new occupancy-tax revenue for the town.