The debate over Great Barrington Airport's activity and the noise and disturbance it produces has been contentious for decades. Better information and consistent zoning enforcement would help.

∎ ∎ ∎

Those who have raised concerns about activities at the Great Barrington Airport (GBR) and its impact on the surrounding residential neighborhood point to many issues, but primarily an increasing number of flights and the accompanying noise and disturbance; assorted environmental risks; safety concerns given recent accidents; and worries about what unfettered growth could mean, especially for those nearby who say things have already become too busy.

The planes “never leave the local airspace,” one neighbor said about increased weekend activity, “filling the beautiful … sky with their deafening roar.” Others can’t enjoy their properties because of pilots who fly in Great Barrington but live elsewhere. “Many of us have found it impossible to even carry on a conversation outdoors from the assault of the noise over our heads,” one said. “And why should local taxpayers be penalized for an out-of-state group’s recreation?”

A longtime airport abutter who “didn’t think twice” about building his house next to the airport years ago now finds that the sound of locally intense flight traffic “drones and reverberates for minutes at a time, never quite getting out of hearing range,” he said. “[The planes] stick to nearly the same pattern for flight after flight after flight.” Another nearby resident told the Selectboard, “The motor noise can be heard whether the particular ascending pattern is over one’s property or far in the distance.”

Many insist they don’t want the airport to close but just want a more considerate neighbor. “No one except the paranoid airport apologists themselves has ever suggested offing the airport,” one said with obvious annoyance. “The complaint [is that] the airport violates the town bylaws because [it] failed to obtain the required special permit.”

Others point to misleading statements from the airport’s ownership: “Good manners and straight answers are obviously not the airport’s forte,” said one critic, frustrated with her unsuccessful effort to get accurate information from the airport about its operations. Another suggested sarcastically that “the airport must continue to enjoy total immunity from town bylaws no matter how devastating the effect upon the neighborhood. The airport has all the rights, the neighbors none. If the neighbors dare complain, they are obviously ‘selfish.’”

Among pilots and others who see those complaints as a threat to the airport, their passion is evident, their arguments consistent, and their animosity toward those who raise concerns sharply stated. “[The airport] has been a valuable asset to this town and should continue to be one unfettered by any constraints that a selfish malcontent might wish to impose,” said one pilot who lived near the airport for two decades. Another pointed to its storied history: “During [its] long period of operation, the airport has provided jobs, added to the area’s commerce, provided air transportation, and been a good participating neighbor in the community,” he said.

As for noise, they say the decibels produced by a passing truck are no different than what comes from a piston-engine airplane circling overhead. And besides, they say, the airport does everything it can to minimize disturbance. One local pilot who introduced his children to the wonder of flight at GBR insisted, “[T]his airport strictly enforces noise-abatement procedures with its pilots. We all recognize our responsibility to maintain the tranquility of our community.”

Giving any credence to the concerns of neighbors—who, after all, bought homes near an airport—would also be dangerous, another longtime local pilot said. “It will not be long before this complainant or others will ask for further restrictions on the airport, and at some point, it will no longer be economically feasible to continue the operation.” Another, joining a chorus of personal attacks, sharply criticized the “relentless nagging and whining.”

For their part, the airport’s attorneys insist that most, if not all, regulation is in the hands of the state and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). They say local officials, from the Selectboard to other municipal boards, have no real authority under zoning or local ordinances to tell the airport what it can or can’t do. In response, the town’s legal counsel warned that zoning matters related to airports present complex issues that often lead to litigation.

The issue of “the airport” has long been, for some, a stand-in for other concerns about the evolution and direction of their community. That includes notions about who is really a “local,” assorted unseemly prejudices, and baseless assumptions about motives. One Great Barrington resident said the “complainers” are “a bunch of people who’ve just moved up here from the city”— even though many have lived near the airport for decades, generations, and in some cases their whole lives.

Those who offer nuance, or facts that partisans find inconvenient, or who propose a middle ground are shouted down. Like the neighbor who said he loves the airport but had concerns about recent activity: “Let’s keep the airport and all it stands for, but, at the same time, not lose the quality of life in South County … on our warm-weather weekends.”

The debate on airport-related issues has fueled troubling division, anger, and distrust. And perhaps it is darkly ironic that advocates for one position or another routinely blame others for fueling that division, anger, and distrust—even as they hurl their own insults, invective, and misinformation. The tension has increased so much that that some are afraid to speak out and others publicly express concern for their personal safety.

That none of this acrimony started recently is made clear by the fact that every quotation and reference prior to this sentence is from 1990, drawn from the letters-to-the-editor sections of the Berkshire Eagle, Berkshire Courier, and Berkshire Record. And also from documents submitted to Great Barrington municipal officials that year and from minutes of 1990 town-board meetings.

That it is nearly indistinguishable from today’s rhetoric suggests little progress has been made over three decades to bridge divides or fill longstanding information gaps that might advance a more productive community conversation that improves prospects for a balanced and permanent solution. It is also fair to say that community fractures evident in Great Barrington and South County back then are certainly no smaller: Considering the evolving local economy and its changing demographic profile, including escalating housing costs and less economic diversity, those real or perceived divides are arguably wider and more complex.

As it relates to the airport discussion, today’s fire is further stoked by a seemingly endless torrent of social-media misinformation, outright fabrications, and personal attacks. Commentators from near and far are emboldened and encourage each other, communicating online in ways they wouldn’t in other venues. Similar condemnations of both pilots and airport neighbors were levied in 1990 using language and claims little different than what’s hurled today; back then, it escalated in troubling ways.

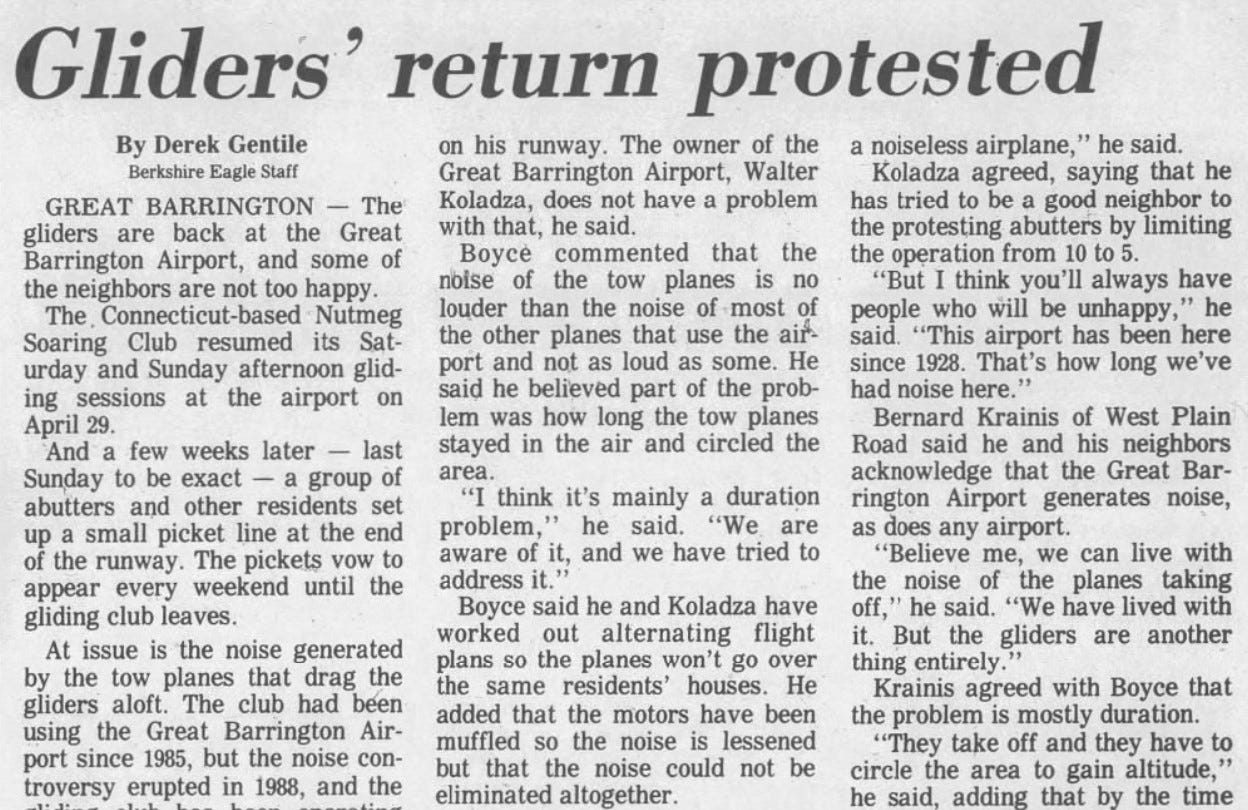

The arrival of gliders

What sparked the 1990 affair—which had its roots in the mid-1980s but mostly played out from July 1990 through the end of that year—was the return of gliders and their noisy tow planes to GBR. The Nutmeg Soaring Club, a Connecticut-based organization, had paid airport owner Walter J. Koladza a fee of $10,000, or about $28,000 in today’s dollars, for permission to launch gliders from his field on one midweek afternoon and for much of both weekend days during the summer—and, weather permitting, deep into the fall.

The club, made up of 80-odd pilots, first arrived in Great Barrington in 1985 after the new owner of the Canaan (Conn.) Airport kicked them out, citing years of noise complaints from neighbors in North Canaan and over the border in Ashley Falls, Mass. That well-known fact wasn’t enough to convince Koladza, the airport’s owner since 1945, to turn them away.

Almost immediately, they raised hackles and complaints from those living nearby: Neighbors told town officials that intense noise from tow planes circling the airport represented a marked change from the longstanding airport norm. A July 1985 news story in the Eagle highlighted a hastily organized signature-gathering effort that protested the gliders. Some letters to the editor complained about the weekend-long noise; others, including one sent by airport neighbor Hilda Banks Shapiro, said it wasn’t much worse and the gliders were beautiful to watch.

Betty Krainis, a founder of the Great Barrington Rudolf Steiner School who lived near where the school is today, told a reporter, “We would like to keep our relations with the airport friendly, but we feel the quality of life in Great Barrington has deteriorated because of the gliders.”

But Koladza dug in his heels. “This is a commercial airport and people are free to fly in and out,” he told an Eagle reporter. Using an oft-repeated—if not quite accurate—comparison, he added, “When a truck drives down the road and makes a lot of noise, people don’t write petitions complaining about it.”

Today’s airport discussion often includes descriptions of an earlier age when Koladza bent over backwards to successfully keep the peace with his neighbors. But that was clearly not always the case. “I have to make a living just like everybody else,” Koladza said defiantly about renting the field to the gliding club. “I’d hate to go out of business just to please the neighbors.”

Allowing the gliders—and the trouble he must have known they would bring—was almost certainly an economic decision, as the airport was likely facing financial headwinds. By the mid-1980s, funding for post-Vietnam GI Bill benefits that paid for veterans’ flight training, and which had long boosted Koladza’s bottom line, were expiring. His charter business was also declining, and by the mid-1980s, he had sold some planes used for charter flights. He would later say he liked having the gliders “because it keeps the airport busy.”

Even if Koladza was focused on revenue, Raymond Duhaine, the president of the gliding club, at least acknowledged the noise. “We try and shut down early and start up late,” he told the Eagle. “The drone from the tow planes is a common complaint from airport neighbors, so we are sensitive to it.”

In the mid-1980s, at least, narrower hours for some of the airport’s locally intense activities were not enough to address neighborhood concerns. One Hurlburt Road resident told the Eagle at the time, “The tow planes circle around and around and make a tremendous amount of noise,” he said. “The regular airplane traffic doesn’t bother us, but the tow planes do.”

After a few years, during which at least one request was made for zoning enforcement under a still-present bylaw provision that blocks any increase in “objectionable … noise or vibration,” the gliding club relocated back to a different Connecticut airfield. For his part, Koladza insisted their departure had nothing to do with neighbors’ complaints. And he stressed it might not be permanent: “I don’t want to say, ‘no they won’t be here,’ because they might come back,” he said in June 1988. And a couple of years later, they did.

A near tragedy on Seekonk Cross Road

But before their return, which would set off an eight-month-long imbroglio, some things happened at GBR that exposed the first inklings of a community divide that would be on full display by December 1990—and, arguably, re-appear in similar form during the airport debates of 2017, 2020, and the one that’s ongoing this spring.

As detailed in part two of this series, Koladza bought the airport in 1945 and had, over the course of four decades, expanded its facilities and operations without acquiring required town approvals. But he did so with few public complaints from those living nearby. Depending on who you ask, that’s attributable to Koladza’s sensitivity to his residential neighbors; fewer (or different) people living nearby; or simply an understanding that complaining to town officials, who had long winked at the airport’s skirting of zoning rules that applied to everyone else, would not be fruitful. But some chinks soon appeared in the airport’s armor.

In April 1987, Honey Sharp Lippman was driving her two young daughters home from the Steiner School (today called Berkshire Waldorf School), which is adjacent to the airport on West Plain Road. She remembers it as “a beautiful, sunny day.” Though Lippman typically turned north onto Seekonk Cross Road toward her home on Division Street, on that afternoon she turned the other way.

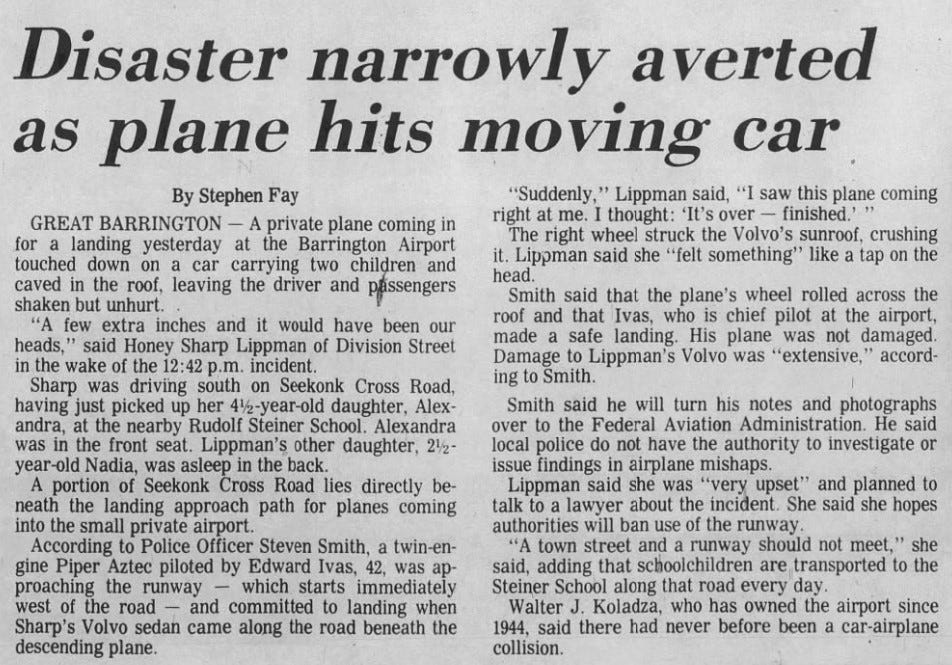

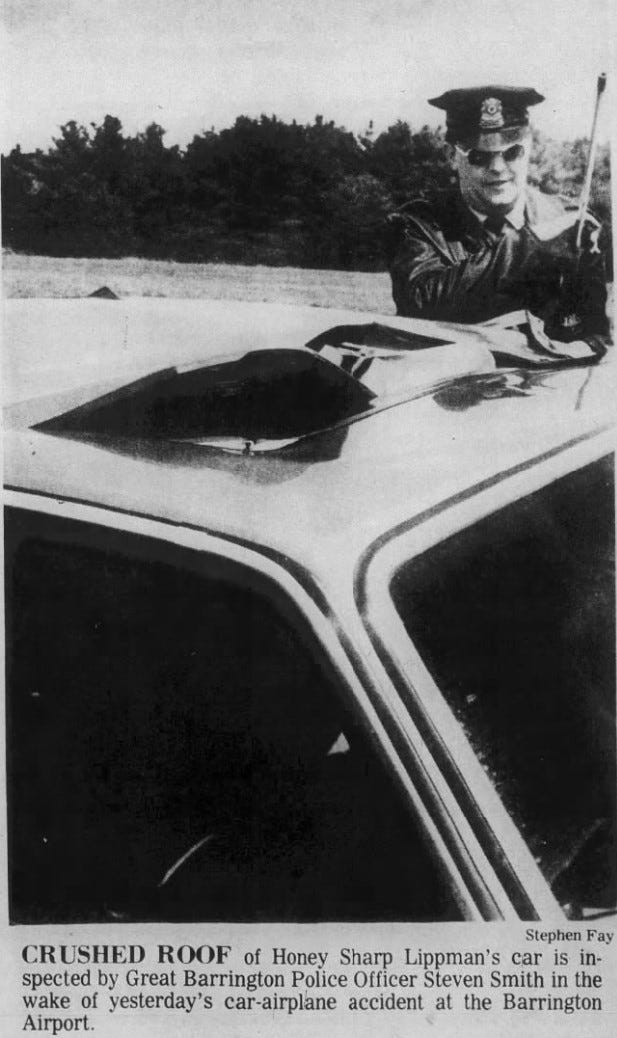

As she headed south on the rural two-lane road, enjoying the bright, early spring, she reached up to open the sunroof of her Volvo. At that moment, as she passed the end of the airport runway—which abuts Seekonk Cross Road—her car was struck by the wheel of a landing airplane, crushing part of the roof and pushing the car onto the shoulder. The plane, a powerful twin-engine Piper Aztec, was piloted by Edward Ivas, a longtime Berkshire Aviation Enterprises (BAE) charter pilot, flight instructor, aircraft mechanic, and one of four men who would inherit the airport after Koladza’s death in 2004. An experienced and skilled aviator, Ivas was able to land his charter flight safely, and he and his two passengers escaped injury.

Lippman and her daughters, then ages four and a half and two and a half, were shaken but uninjured; the children were belted into child-safety seats in the back. “I felt like I had a guardian angel after I thought about it,” Lippman told me recently. She said she had never previously considered the runway’s location next to the road. “I don’t remember thinking this is dangerous. Because you assume that a landing plane is going to avoid [a car],” she said.

A news story the next day about the accident quoted Lippman’s definitive view: “A town street and a runway should not meet,” she said, proposing that use of the runway should be prohibited. No doubt that was a startling and concerning idea to those who owned, worked at, used, or otherwise loved the airport.

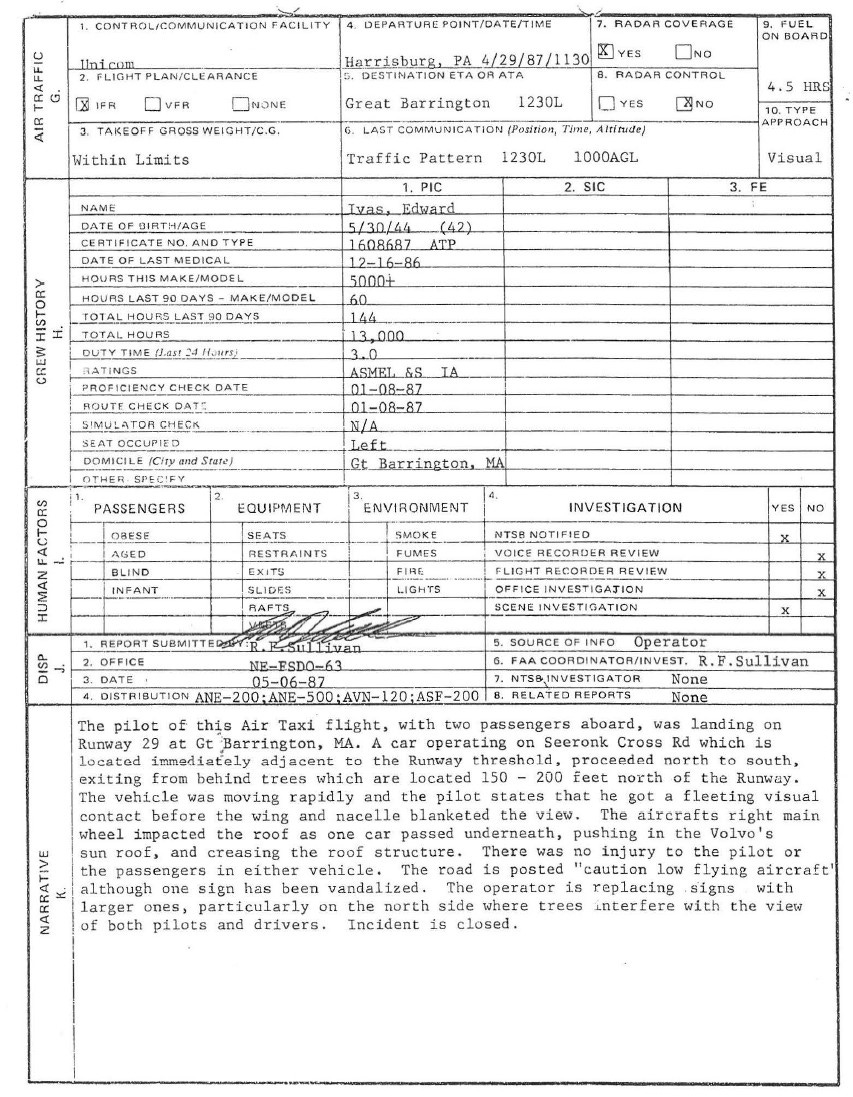

According to an incident report acquired by the Argus via a public-records request, Ivas told an investigator from the FAA’s Bradley Flight Standards District Office near Hartford that Lippman’s car “was moving rapidly and … [he] got a fleeting visual contact before the wing and [engine housing] blanketed the view.” The report highlighted a line of trees on the eastern side of Seekonk Cross that reduced visibility for both approaching cars and landing planes. And it noted the “low flying aircraft” signs. “Incident is closed,” the investigator concluded.

The community response to the near tragedy was divided and surprisingly heated. It revealed differing perspectives on the airport and general aviation that today still seem unreconcilable. Local pilots insisted the onus was on drivers to watch for landing planes, and Koladza told the Eagle that despite his low-flying-planes signs, “I still see those cars zipping down the road. They just move too fast.”

Meanwhile, a host of residents, including 138 who signed a petition calling for unspecified safety measures, argued that roads are meant for drivers, and it’s not their responsibility to be alert to sudden dangers from above. After all, pilots have standard glide-slope approaches and shouldn’t be at car level before reaching the runway. “The airplane-automobile accident on April 29, 1987, is shocking and points out the danger to motorists and pilots of Seekonk Crossroad and Runway 29,” the petition sent to the Selectboard began. “I would like to see proper measures taken to make this area safe.” Parents and town officials also expressed concern about buses traveling to the nearby private school and the safety of others, especially children, who passed the road-runway intersection in cars every day.

A threat to the airport

For perhaps the first time since it was shuttered for a period after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the airport encountered a legitimate threat to its operations—and possibly to its existence. And those connected to it unquestionably closed ranks. An article in the Eagle, headlined, “Near misses put Barrington Airport on collision course with residents,” featured stories from others who reported close calls including a car that was struck by a glider-tow-plane line. Neighbors expressed further worries about the safety of children.

There was no social media, so opinions were expressed in the newspapers. Willard Brown, who lived on Christian Hill Road, wrote that he occasionally chartered flights from the airport and complimented Ivas’ great skill. He suggested that was the point: “If a professional like Ivas can have such an accident, is it not even more likely that pilots with less experience and training would be prone to have such an accident—and at greater frequency?”

The Selectboard and town officials soon met to consider various options, from re-routing Seekonk Cross Road to closing it to all traffic. Some in Great Barrington even called for closing the airport, at least until a solution was found. State aeronautics officials—who dismissed any suggestion of closing “an important airport”—said they would examine the angle of descent used by pilots on final approach.

After a discussion held at the end of the runway with town officials, residents, and state officials, the town immediately installed two stop signs on Seekonk Cross Road on either side of the runway, posted a 35 mile-an-hour speed limit, and asked Koladza to keep his low-flying-planes signs free of graffiti and clearly visible.

Of the stop signs, Koladza said, “[They’re] a great idea. Anything that would make a driver slow down and look … it would make them a little more careful.” Koladza also agreed to move the runway threshold about 50 feet to the west and said he would advise pilots to be more careful and “just stay up there a little [bit longer].” He said that, like others, he was concerned about the problem and would implement any other recommendations made by state aeronautics officials. (The stop signs were removed about 20 years ago.)

Today, particularly with an acknowledged increase in the number of student pilots learning at BAE’s respected flight school, some have again pointed to the danger at that intersection. Though Erik Bruun, the chair of the Board of Trustees at the Berkshire Waldorf School, told me recently that he’s never heard any complaints or any requests for stop signs. “If there was a strong feeling within the school community for that to happen, I wouldn’t object to it,” he said.

Troubling undercurrents

Looking back from more than three decades later, Lippman told me she was surprised by the furor over what to her seemed uncontroversial: Planes should watch out for cars. “There was a kind of finger pointing at me,” she said. “Which was so absurd. I just find it hard to see the other side on that issue. I just think it’s a certain mentality.”

After she and others spoke out about their safety concerns, Lippman became a target of sharp criticism. It was an unlikely position for someone who had just barely escaped calamity—even if a car-plane collision had never happened before and hasn’t happened since. One remarkable letter published in the Berkshire Courier during the subsequent glider controversy went so far as to suggest, in print, that Lippman had “stopped [her] car intentionally(?) beneath a landing plane expecting an outcry which could help continue the feud.” That Lippman had her two young daughters in the car seemed lost on the letter-writer.

She never received an apology or any communication from Koladza or anyone associated with the airport, she said. And she received concerning, anonymous hate mail sent to her home that she asked me not to describe in detail. “Suddenly I learned that there’s a whole other side,” she recalled, unnerved by what was written and that it came from someone in a community she thought she knew well.

There continue to be anecdotal reports of close calls, including from those who are opposed to granting a special permit to the airport. A video showing a landing plane crossing Seekonk Cross Road at car level was first posted online in 2020 and is today featured on the GBAirportFacts.com website launched by Anne Fredericks and her husband Marc Fasteau, the Seekonk Cross Road neighbors who initiated the 2021 zoning-enforcement request that’s now in Land Court.

According to MassDOT’s Transportation Data Management System, in 2021 there were an average of 239 trips across some part of Seekonk Cross Road each day. That has remained steady since the agency did an on-the-ground, 24-hour traffic count in 2014. When I asked Kristen Pennucci, a MassDOT spokesperson, who has the right-of-way at a runway-road intersection, she said the agency doesn’t have a policy addressing that question. She said MassDOT defers to federal regulations on runway obstructions; those regulations primarily address rules for submitting new construction projects for FAA review.

Another unprecedented event that unsettled neighbors and the broader community—and which was an actual tragedy, rather than a near miss—was a January 1990 plane crash that killed two people moments after takeoff from the airport. A group of six people in their 20s and early 30s had rented a plane in Farmingdale, N.Y., on Long Island, and flown to the Berkshires for some night skiing. After landing in Great Barrington and learning that Catamount in neighboring Hillsdale was closed, the group decided to fly north to Pittsfield for skiing at Bousquet Ski Area.

Flying in the dark, and unfamiliar with both the airport and the flight pattern, immediately after takeoff, the pilot turned to the south too soon. The plane, a Piper Lance, hit some trees and crashed just over the Egremont line, barely missing two houses. Four others aboard the plane were injured. It was reported to be the first fatal accident at or near the airport in its long history.

The gliders return

The Nutmeg Soaring Club returned to Great Barrington in late April 1990. They were back, not surprisingly, because they had been forced out of another Connecticut airfield due to noise complaints and because other pilots didn’t like them clogging the flight pattern. So it was also no surprise that Koladza soon received the usual complaints and, once again, calls for the gliders to leave.

While gliders that float gracefully on the wind and stay aloft via currents known as thermals are perhaps as silent as owls chasing nighttime prey, airport neighbors learned in 1985 that the tow planes that haul them skyward are more like roaring lions. And not just loud, but frequent, too.

Back in 1990, the airport’s defenders argued adamantly in letters to the editor and submissions to town boards that tow planes were no different or louder than any other plane. But today they no longer make that claim. “The gliders were obnoxious,” Rick Solan, BAE’s majority owner, told me during a conversation one morning last December. He said that, in 1990, the gliding club typically had two tow planes running all day, circling near the airport and flying over homes on Berkshire Heights. “All day long, they would vibrate, because it was like an echo chamber,” he said, describing the open valley where the airport sits. He also confirmed that Koladza was happy to bring in that $10,000 a year. “It paid his taxes,” Solan said.

In 1990, Solan was in the early years of what would be an accomplished career as a pilot and instructor at American Airlines. But he was also still spending time helping Koladza, who first taught him to fly in the 1970s. He would, after Koladza’s death in 2004, become one of the airport’s owners and soon thereafter control a majority stake. So he was regularly at the airport that summer and fall when the gliders controversy reached a rolling boil.

His name was mentioned in one 1990 letter sent to the town. It complained about the gliders droning overhead “for a large portion of the day”—but it also complimented Solan for his responsiveness. “My call to the airport, to I think a Mr. Solan, received a positive response and immediately the planes changed route,” a neighbor wrote. “This, of course, to our delight. However, we continue to see gliders and we know the nuisance has only been transferred elsewhere. I like the airport but dislike the drone of the glider [tow] planes.”

Noisy tow planes and noisy neighbors

Before long, letters flooded the local papers. “Alas, they are back again,” one said, asking that Koladza “consider the feelings of his neighbors and help preserve the serenity of the beautiful area” near the airport. An instructor from the gliding club acknowledged that the problem was one of “duration,” given the constantly circling planes. A group of neighbors set up a weekly picket line near the end of the runway to protest—perhaps with earplugs inserted, given their concerns. But that’s just conjecture.

As in 1985, Koladza would not be moved. He said he did his best to accommodate the neighbors by limiting the gliders’ weekend operations to 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. “But I think you’ll always have people who will be unhappy,” he told longtime Eagle reporter and columnist Derek Gentile. “This airport has been here since 1928. That’s how long we’ve had noise here.” He and others also said the gliders’ tow planes now had $1,500 mufflers installed on their engines, but clearly they didn’t help much.

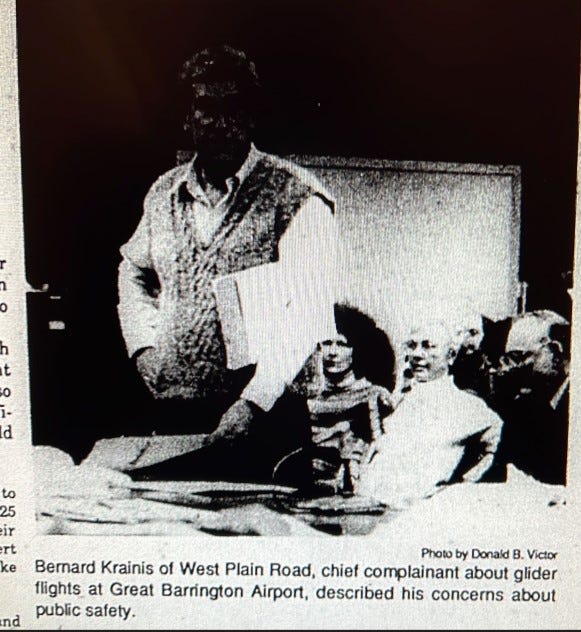

Koladza’s primary and fiercest critic quickly emerged from the growing din. Bernard Krainis, an acclaimed classical musician known internationally for playing baroque music on the recorder, had lived near the airport with his wife Betty since 1960. As he did when gliders first arrived in 1985, he sent letters to the newspapers and offered quotes to reporters covering the story. “Believe me, we can live with the [usual] noise of the planes taking off. We have lived with it. But the gliders are another thing entirely,” he told the Eagle.

Krainis was no doubt a prickly spokesperson. In years of letters to the editor on myriad topics, he was never one to mince words or express his strong opinions with delicacy or collegiality. But just as airport neighbors have been in recent years, he was frustrated by the airport ownership and town officials who seemed unwilling, once again, to take any action.

As if it had been scripted for the made-for-TV-movie version of the story, as the campaign against the gliders gained steam in late July, a glider pilot misjudged the distance to the runway and crashed—right into the yard of Bernard Krainis. Luckily, no one was hurt in the Saturday afternoon accident. Koladza told the Eagle it was “nothing serious,” which led Krainis to criticize both Koladza and the Eagle’s minimal coverage.

Krainis, who was standing outside just as the crash happened, expanded his list of concerns to include not just noise from the airport but also the potential danger to nearby residents. He said Koladza “is responsible not only for the assault on his neighbors’ nervous systems but, it is now apparent, he also places in peril our lives and property.” Combined with the fatal January crash and still-simmering reaction to the Ivas-Lippman incident, the airport now faced mounting criticism.

The president of the gliding club, L. Corwin Sharp, sent a letter of appreciation to the Great Barrington Police, thanking them for the force’s “prompt, efficient, and professional manner” at the site of the crash in Krainis’ yard. Revealing a not insignificant lack of knowledge of the community in which his club had stirred up controversy, his letter was carbon-copied to “Mayor, City of Great Barrington.”

In a letter to the Eagle about the crash, Krainis included details that a biographer might use to sketch the man: “At approximately 1:00pm, Saturday, July 21, I had just finished picking Japanese beetles off the potentilla bush at the east end of my driveway,” Krainis wrote. As he turned to head inside for lunch, he heard “a strange ‘whoosh’” and saw the glider hit a tree about 30 yards away. Had it crashed 50 yards to the east it would have been in a field where Steiner School day campers played during the week, Krainis said. (For their $10,000 annual payment, the gliding club also flew on Wednesday afternoons.)

Krainis announced plans to speak to the Selectboard at their Monday night meeting, two days after the glider crash. But Koladza showed no interest in a discussion: A few hours before the board’s meeting, he told an Eagle reporter that he wouldn’t attend because, as the reporter summarized, “he [said he] has a business to run and better things to do with his time.” For his part, Krainis said the issue had grown. “It’s no longer a matter of noise. It’s a matter of safety,” he told the Selectboard.

The Eagle chimed in with a short editorial titled “Glided Missiles” that called for an investigation; a few months later it endorsed a complete end to glider operations. And the Selectboard, hinting that it couldn’t or wouldn’t do much, at least said it would look into the matter.

Tragically, less than a week later another fatal crash near the airport shook the community. Paul E. Thorn, a 68-year-old pilot from Monterey, had just taken off from GBR when his plane’s engine gave out. The Lake LA-4 plane he was flying crashed not far from the site of the fatal January crash near the Egremont-Great Barrington town line and burst into flames, killing Thorn and seriously injuring his son, also named Paul, who was the only passenger. An NTSB investigation found that the plane’s engine was in poor condition and that a recent annual maintenance inspection had been “inadequate.”

Applying the zoning bylaw to the airport

After three accidents close to the airport in seven months, with two of them causing fatalities, safety concerns were now part of the community conversation. The town was split along predictable lines on whether there was any significant danger, with pilots and airport boosters pointing to the airport’s long prior history with no fatal accidents. Still, Steiner School administrator Sallie VanSant wrote to Koladza and focused on the nearby glider accident. “The safety and well-being of 226 students [are] my primary concern,” her letter began. “I am formally requesting that glider flights be prohibited between the hours of 8:00 A.M. and 5:00 P.M., Mondays through Fridays, in the interest of protecting our school children from possible danger,” she wrote. “I’m sure you can understand our concerns, and I’m hopeful we can find a common ground to stand on.”

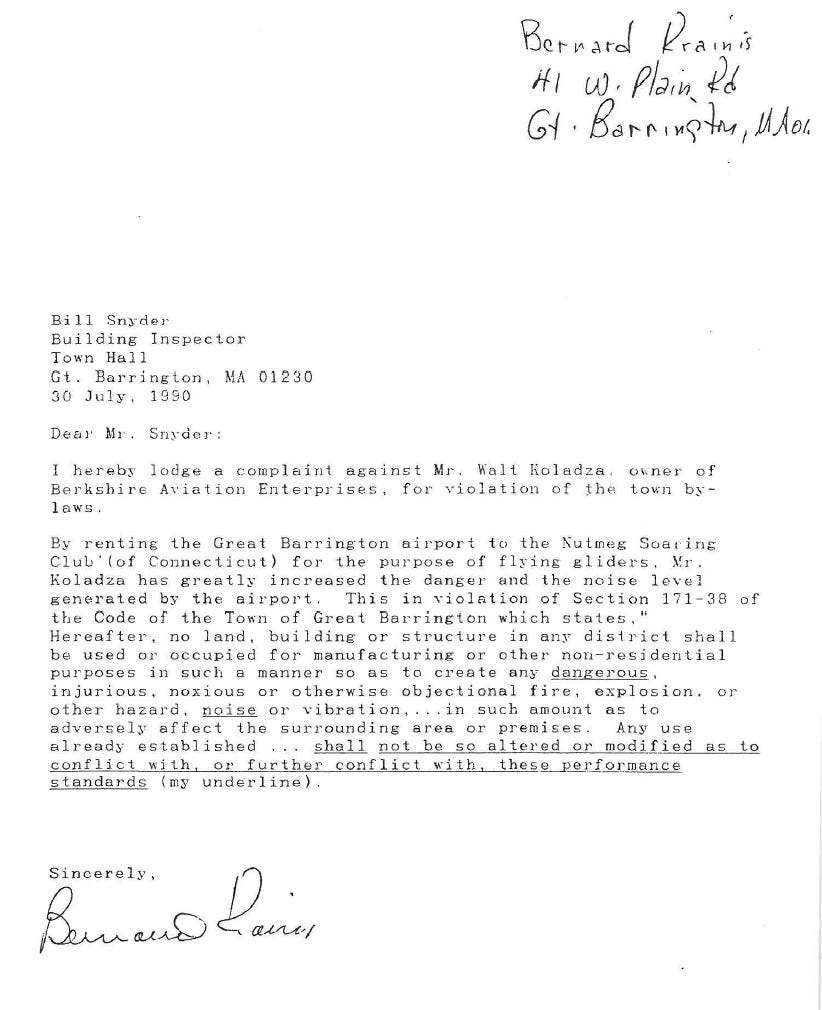

Krainis appeared again at the next week’s Selectboard meeting, this time armed with commentary and a list of suggestions titled, “The Great Barrington Airport—A Perspective.” Noise pollution “is increasingly recognized as a threat to human health and well-being, and like any other pollutant must be carefully regulated,” Krainis began. He detailed his initial zoning complaint, in 1986, which the building inspector turned down citing FAA jurisdiction—a position advanced by the town counsel at the time, Paul R. Corbett. Krainis said that, when he contacted the FAA, the agency told him it had no jurisdiction over a privately owned airport. “Walt Koladza, therefore, appears to be the only citizen in Great Barrington who is exempt not only from the town bylaws but from any regulation of any sort,” he said. “He is in the enviable position of operating entirely outside the kinds of restraints the rest of us must live with.”

Hinting at violations now at the heart of the case in Land Court, he suggested the “creeping escalation” of activities at the airport, including the addition of helicopter flights and a beacon light that “without a special permit would also seem to fall into the category of bylaw violations.” And he said Koladza had invited gliders and tow planes “without consulting his neighbors or considering the impact this activity would have on the neighborhood.”

Among his suggestions was “bringing the airport within the jurisdiction of the town’s by-laws,” along with studies of noise, a new tax on the airport, and nonspecific “regulation” that would “minimize to the greatest possible extent its adverse effects on the community.”

A few days later, Krainis, who had been elected to the Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) in 1986 and was more familiar with the zoning bylaw than most, did what Holly Hamer, Marc Fasteau, Anne Fredericks, and other neighbors did in 2021: He sought enforcement of the zoning bylaw. In his letter to Building Inspector William Snyder Sr., Krainis argued the gliders were a violation of a bylaw provision related to noise and vibration and represented an impermissible change to a “use already established.”

As he had in 1986, Snyder sought advice from town counsel. Attorney Bart J. Gordon, a respected Springfield attorney, told Snyder in a letter that he would have to “do some research to determine the history and extent of past authorization and use, including noise. The issue for you is likely to be whether there has been a change or alteration of a non-conforming use which will subject the use to application of the Zoning By-Law.” Gordon also wrote that any changes at the airport must represent “a significantly different impact on the neighborhood … this inquiry may require a detailed factual analysis.”

Gordon also cited case law that he said “pretty clearly” established that private airports are subject to zoning regulation; though, he noted there can be federal pre-emption on some issues. He ended his letter to Snyder with a warning: “Airport zoning issues are very complex and often litigated, and I caution you to be particularly careful to document the positions of the parties.”

Krainis followed up with a second letter documenting what he said was, among other things, the “intensity and duration” of tow plane activity that “create[s] entirely new and intolerable levels of noise pollution.” He also suggested that “the routing of tow planes directly over my house the day after I registered a complaint to the Selectmen (and often thereafter) would seem to be somewhat more than a funny coincidence.” And while he conceded he couldn’t prove it, he said that was evidence that Koladza sought to “punish neighbors who dare to complain about his un-neighborly activities” and was using “gliders as a weapon.” And in a statement that echoes recent disputes about airport activities, he said that Koladza’s claim that the days and hours of glider activity were strictly limited was “simply and demonstrably false.”

He included signed statements that, together with his, brought to 18 the number of airport neighbors and other residents who formally attached their names to the complaint. He also noted 116 petition signatures from other residents supporting the effort, and concluded, “I urge you to issue immediately a cease and desist order banning the operation of gliders … unless and until a special permit has been obtained for that purpose…”

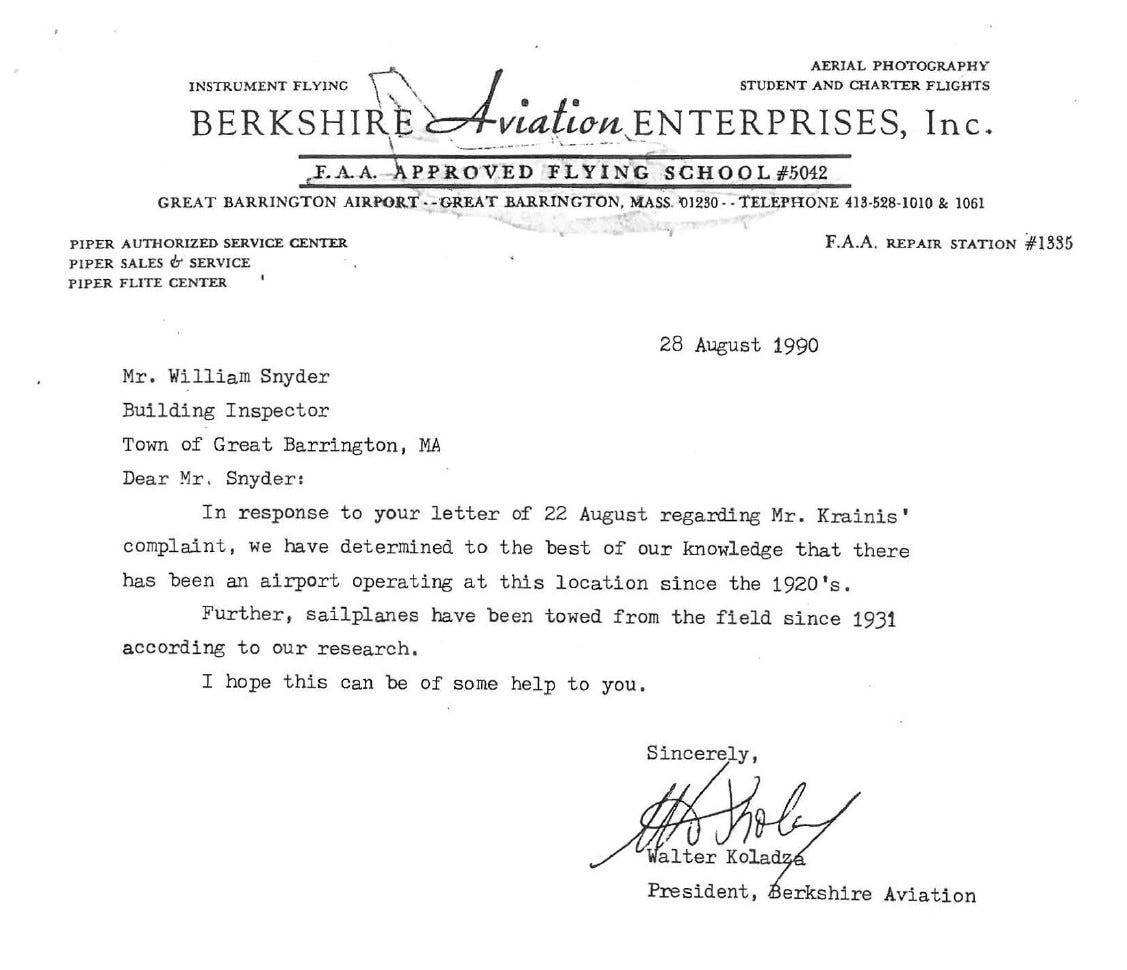

For his part, at the end of August, Koladza sent Snyder a brief, three-sentence letter. “We have determined to the best of our knowledge that there has been an airport operating at this location since the 1920’s. Further, sailplanes have been towed from the field since 1931 according to our research. I hope this can be of some help to you.”

At the time, some press coverage erroneously said the issue was about the airport’s violation of the town’s new noise ordinance. That wasn’t the case. In fact, when the town approved the noise ordinance a year earlier, in 1989, it provided a blanket exemption for the airport. That wasn’t in the original proposal placed on the warrant by the Selectboard, but someone—neither news coverage nor the official minutes of the meeting identify who it was—made a motion to add the airport to the list of exemptions and it was approved.

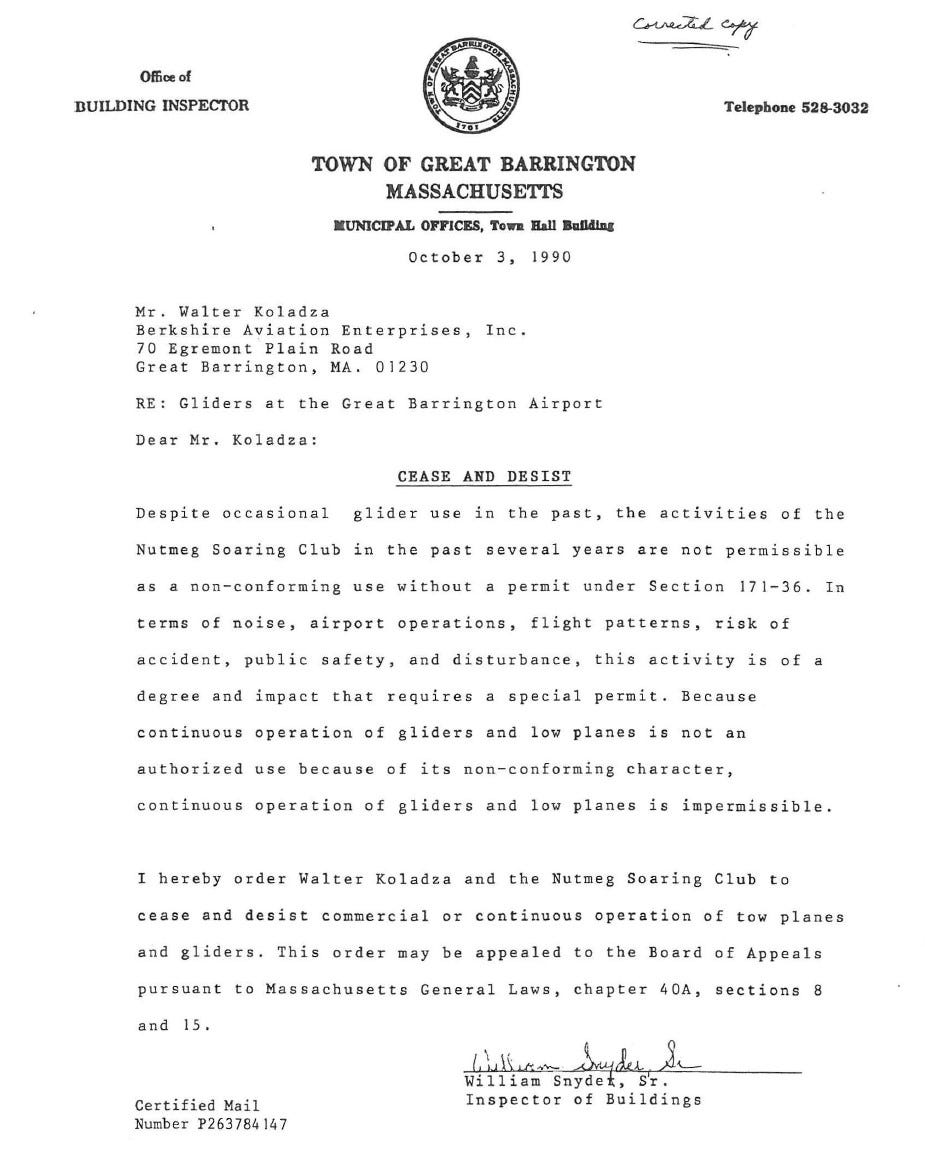

The cease-and-desist order

For the first time in its history, in early October, the airport was subject to zoning enforcement. “I hereby order Walter Koladza and the Nutmeg Soaring Club to cease and desist commercial or continuous operation of tow planes and gliders,” Snyder wrote in an order sent to the airport via certified mail. “Despite occasional glider use in the past, the activities … in the past several years are not permissible as a non-conforming use,” the order explained. “In terms of noise, airport operations, flight patterns, risk of accident, public safety, and disturbance, this activity is of a degree and impact that requires a special permit.”

Almost immediately, Koladza announced he would appeal the order to the ZBA, and both sides of the issue continued their signature-gathering and letter-writing. Doug Stewart, a longtime pilot and accomplished flight instructor who worked for BAE for years, told me that he collected nearly 160 signatures in support of Koladza and the gliders. He also later presented the ZBA with a map showing a majority of the signatures came from residents within a mile of the airport. Among the signers? Claudia Shapiro, the airport abutter who has feuded for years with the post-Koladza BAE ownership, and Mike and Julie Peretti, airport neighbors who are today listed in court documents as supporters of the Land Court action.

Of course, letters to the three local newspapers were soon churned out as if by enormous machines. As quoted earlier, the rhetoric mirrored almost exactly what’s said today. (The Courier ran an editorial in advance of the hearing noting that “a lot of information and some mis-information has been aired in this newspaper’s letters pages in recent weeks…”) And when the doors to the Town Hall meeting room were unlocked for the ZBA’s December 3, 1990, airport hearing, an estimated 150 people poured into the room.

George Beebe, the local farmer who owns land near the end of the airport runway and was a member of the ZBA at the time, told me the division in town was clear. “There were two sides [in the room], one for the airport and gliders, and on the other side were all the people who wanted to stop it,” he said. “There was no middle ground.”

Koladza was represented by Paul Feldman, the Boston land-use attorney who has handled cases in the Berkshires since the mid-1980s, when he represented Robert Hatch, the owner of the Stonegate time-share on West Avenue. More recently, he represented Gary J. O’Brien in the long-running and contentious zoning matter related to O’Brien’s trucks and business on Roger Road.

Feldman made familiar arguments: Gliders and tow planes had long been used at the airport, he said, including before zoning was enacted in 1932, and were therefore established as part of the airport’s preexisting nonconforming use. And he stressed that, in any event, the town couldn’t regulate flight operations at the airport because local rules were pre-empted by federal regulations.

But the arguments from Krainis and others must have been persuasive: A Berkshire Courier editorial a few days later, after the hearing had been continued to December 13, said that the evidence and the board’s deliberations so far “don’t bode well for the airport’s case.” Overturning Snyder’s order would take four-out-of-five votes, and it didn’t appear they were there.

A surprising turn

News coverage in advance of the second hearing focused on the strong and seemingly irreconcilable feelings on either side of the issue—much like today. Included in the mix was an argument from glider proponents that if the cease-and-desist order wasn’t overturned, it could mean further action to constrain the airport and eventually shut it down.

Evidence that this was all taking place in a small town emerged the day before the second hearing. An Eagle story featured news that two members of the three-person Selectboard supported keeping gliders at the airport. “Ed [Morehouse] and I have never been opposed to the operations of gliders at the airport,” said the board’s chairman, Richard J. Louison. “As far as I’m concerned, the gliders can operate there for as long as the airport is there. I have no problem with them,” Louison said. But he also insisted, “We have nothing to do with it,” saying it was a decision for the ZBA.

After nearly 60 years of town officials looking the other way when it came to the airport and zoning, the building inspector had acted. So it was certainly noteworthy that, in the middle of the ensuing storm and with a strong case presented in support of Snyder and against the gliders and the airport, the Selectboard chairman chimed in when he did. It’s worth considering that at the time, the town’s building inspector was hired—and could be fired—by the Selectboard.

Whether that played a role in what happened next is hard to say. But the following night, just as the ZBA prepared to resume its deliberations, Snyder asked to speak. In a brief statement, he said he had changed his mind and would withdraw his cease-and-desist order. He said he had found evidence “in his files” that showed, as Feldman contended, past glider and tow plane activity and that it was not, after all, an impermissible use. (The Eagle’s coverage wryly noted that the movie “Reversal of Fortune” was currently playing next door at the Mahaiwe Theater.)

Feldman was elated. But the local attorney for the glider opponents, James V. Lamme, was among those infuriated by Snyder’s turnabout. “This cowardly, to say the least, attempt to back out of this situation has solved nothing,” he said.

In a letter sent to Krainis advising that the cease-and-desist order had been withdrawn, Snyder echoed language used by Feldman in a legal brief and in front of the ZBA. But he also included some curious statements. “Tow planes are not distinguishable from any other air[craft],” he wrote, something that evidence suggested was not accurate in practice. And he added, “To deny the airport the right to permit gliders would lead to a circumstance where any new airport activity would be illegal”—a statement far out of scope for a building inspector’s ruling on a single zoning complaint. But it was perhaps useful to help pre-empt any future zoning challenges to the airport. And if that was the intent, it worked for 31 years.

If there was, in fact, glider activity prior to the implementation of zoning in 1932, it was almost certainly of a kind that didn’t involve tow planes. Because at the time, gliders were often pulled not by planes but by cars. And in a rich irony, given the airport’s history, a gliding class held at the airport just days after the airport’s dedication in September 1931 was terminated when William Heaton, the aviation inspector for the state’s registry of motor vehicles, found “the school had complied with none of the regulations for gliding,” according to a story in the Courier. The glider they were using was not registered, no permission had been secured to use an automobile to tow the glider, and the airfield had not been approved for it. The classes were canceled.

By the time the ZBA matter was concluded a few months later (there had been an appeal filed contesting Snyder’s right to withdraw his cease-and-desist order), Koladza decided it was time for the gliders to go and he didn’t renew the contract. “And I told him that was wise,” Solan said recently.

In 2001, Snyder resigned unexpectedly—or was forced to resign—after years of grumbling by members of various town boards that the building inspector had, for some reason, developed too light a touch when it came to enforcing the building code, the town’s zoning bylaw, and conditions the boards attached to special permits. He died in 2004.

A ‘furor’ in town

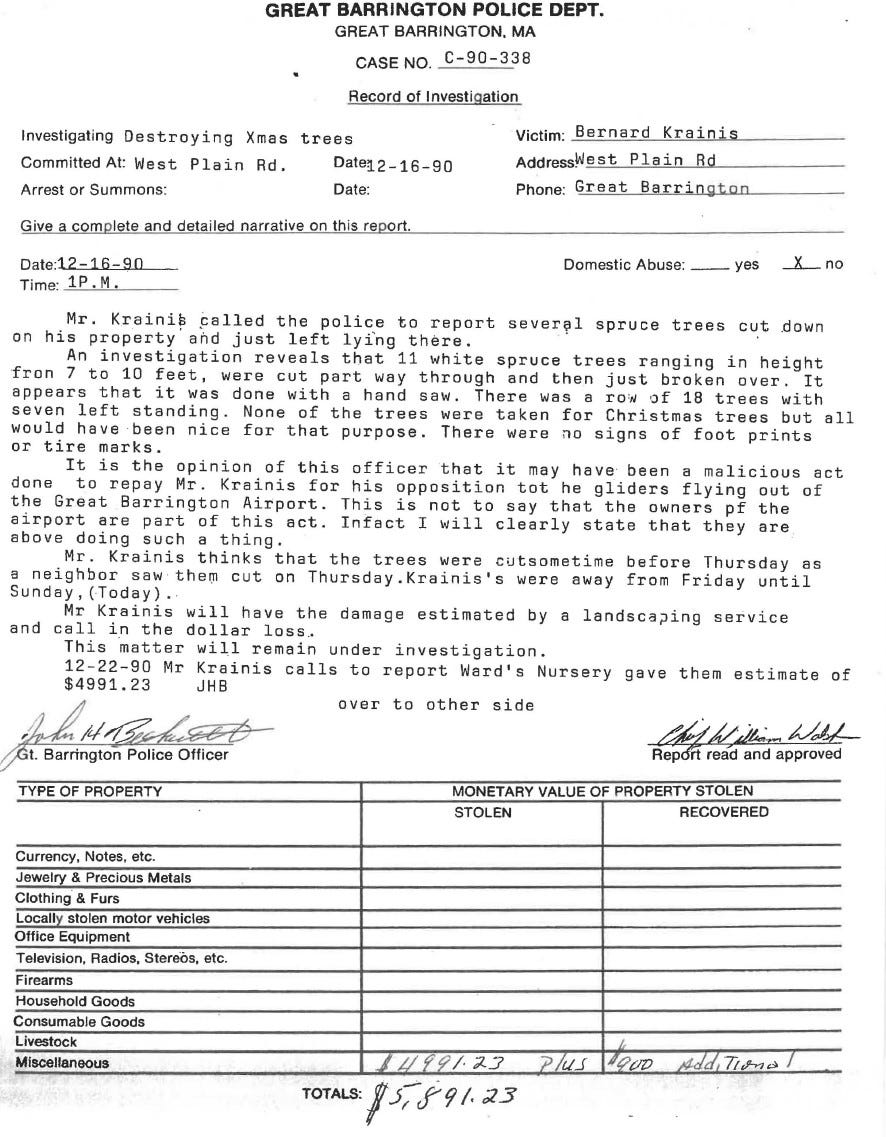

On the night of that second ZBA hearing, when it was likely assumed that outspoken glider opponents would be at Town Hall, 11 trees were cut down at the property of Bernard and Betty Krainis. A police report describing the incident said the trees were each cut part-way “with a hand saw” and then “just broken over.” Officers found no physical evidence and “no signs of footprints or tire marks.”

A few days later, on Christmas eve, three more trees were cut down, bringing the total to 14. Ward’s Nursery estimated the cost of replacing them to be $5,900, or just under $14,000 in today’s dollars, according to the police report.

A week later, a letter appeared in the Eagle headlined “Malice in Barrington.” It was written by Seekonk Cross Road resident Jill Barrett Johnson, who noted that she had lived near the airport for much of her life. “Not until the gliders came did I experience any problem with airport noise,” she wrote, adding that she recognized the airport’s “right to exist.”

But her letter suggested a turn. “During the recent furor over the glider issue, I saw anger turn to downright malice,” Johnson said. “Or is it a coincidence that personal property of four opponents of the gliders was vandalized at the time of the second ZBA hearing?” (Johnson is today listed in court documents as a supporter of the Land Court zoning-enforcement action.)

That police report describing the vandalism at the Krainis property was written by Officer John H. Beckwith, who would later become a member of the Great Barrington Selectboard. “It is the opinion of this officer that it may have been a malicious act done to repay Mr. Krainis for his opposition to the gliders flying out of the Great Barrington Airport,” Beckwith wrote. “This is not to say that the owners of the airport are part of this act. In fact, I will clearly state that they are above doing such a thing,” he concluded.

Krainis called it “terrorism” and said it had upset both his wife and neighbors. “You feel a strong sense of violation and you never get over it. Do they burn the house next?” he said.

There was also vandalism of airport property during another contentious town debate over the airport. In May 2017, as the airport was making its case to the Selectboard for a special permit and permission to build three new hangars, two BAE-owned Piper Cubs used by its flight school were damaged overnight in what airport officials called “a malicious attack.” The plane’s rudders were bent and other damage evident. Fortunately, the damage was discovered before the planes were flown. BAE minority partner Jim Jacobs told the Selectboard that the two planes “were destroyed,” though the Eagle reported that they were back in use after repairs costing “$8,000 to $10,000.” The airport’s manager said he didn’t believe there had ever been a prior incident of a plane being vandalized in the airport’s 86-year history.

According to a detailed police report filed in September 2017, no fingerprints or other evidence were found at the scene by state police investigators. Airport officials told police they believed they knew who had damaged the planes, even though they had “no specific evidence.” The police report identified that person, who was described as the only suspect. Even though maliciously damaging an airplane is a federal crime—for good reason—police said in their report that they were unable to interview the suspect and did not pursue the case further.

Krainis earns a challenge

There were enough people unhappy with Krainis’ high-profile and pointed airport criticism that local Republicans recruited someone to run against him for ZBA in 1991. (His sharply worded rhetoric about the disturbance from the gliders coincided with the Gulf War; in one letter to the editor, he compared Koladza to Saddam Hussein.)

Robert H. “Bob” Jones, a Great Barrington native who is today a member of the Selectboard in Lee, grew up on Division Street. He had long been a fan of both Koladza and the airport. He told me recently that he was asked to run against Krainis. “I got a call from the Republican Party in town and they said, ‘You’ve got to do something about this thing, because of the airport,’” he recalled. “So that was the impetus for running. It must have mattered to me because I became a Republican for 15 minutes,” he joked. “And then [after the election] changed back to independent.”

He had no personal animus toward his opponent. “Bernie Krainis was a really nice guy, a very talented guy,” Jones said, noting that his mother and stepfather were friends with Krainis and his wife. But Jones thought the complaints about gliders and tow planes were “petty and frivolous,” so during his campaign he took the position, popular at the time, that the tow planes weren’t any different than other planes. “I guess people saw it the same way and I won by a pretty healthy margin.” (Jones received 872 votes to 580 for Krainis.)

He takes the same view of today’s complaints, suggesting, from what he said is his perspective as a former ZBA member, that the airport hasn’t undergone any substantial change that requires zoning enforcement.

“People have opinions that don’t always jibe with the zoning bylaws,” Jones wrote in a thoughtful 2008 letter to the Eagle about a different matter in Great Barrington. It was headlined, “Follow the letter of the zoning law,” and argued that facts matter. “When someone purchases a piece of property, they have every right to do what they want with it,” he wrote, “as long as they meet the requirements of the zoning bylaws.”

I had called Jones not only to hear about his 1991 candidacy but also because he has the same name as a 1940s-era federal aeronautics inspector who once passed through Lee. (He also shares the name with his late father, Great Barrington’s Robert H. Jones Sr., who served in the Air Force and owned Jonesy’s Luncheonette.)

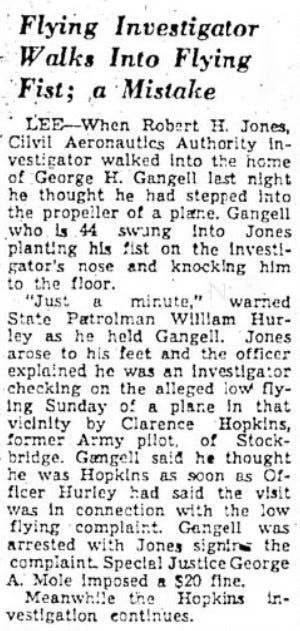

That unrelated Robert H. Jones made the pages of the Eagle in May 1946 for an incident related to aircraft noise. There had been complaints that Clarence Hopkins, a former Army pilot from Stockbridge, had been making noisy low flights over houses in Lee. When a state patrolman named William Hurley appeared at the door of Lee resident George H. Gangell, who had filed one of the complaints, Hurley explained he was there to investigate. The 44-year-old Gangell assumed that Jones, who was standing next to Hurley, was Hopkins, the offending pilot. So he swiftly punched Jones in the face, earning an arrest and a $20 fine. For his part, Hopkins was summoned a few days later to Berkshire District Court to answer for the low flights over Pleasant Street.

By the end of February 1991, both the Gulf War and the War of the Gliders were over. Eventually, the gliding club purchased its own airfield in Freehold, N.Y., about 20 miles southwest of Albany and an hour’s drive from Great Barrington. It’s located amidst mountain ridges that create excellent thermals to help gliders stay aloft. It is also in a sparsely populated area in the Catskills. Today, Solan and BAE have proposed a special-permit condition that would ban gliders and tow planes from the airport in Great Barrington except in the case of an emergency glider landing.

The noise about noise

Complaints about noise and nuisance from Great Barrington Airport are certainly not new. In 1932, just a few months after the town’s first zoning bylaw went into effect and a year after the airport’s dedication, an editorial in the weekly Berkshire Courier under the headline, “Noisy Airplanes,” asked, “Since when has it been necessary for airplanes, with noisy motors, to spend Sunday afternoon flying over a hospital full of sick people, to whom a period of peace and quiet may mean so much?” (Today the airport asks pilots not to fly over Fairview Hospital.)

And just a few weeks after the airport began operations in September 1931, the Courier included an odd half-page advertisement, suggesting that people could be desensitized to annoying sounds by eating certain kinds of foods—particularly candy—at the right time. (The ad ran in dozens of papers across the country and was not targeted only at communities dealing with “planes with noisy motors.”)

As the recent debate in West Stockbridge over noise from a music venue makes clear, measuring, evaluating, and understanding the impact of “noise” is not easy or clear. And one’s view seems, more often than not, to align with one’s opinion on the issue at hand as well as one’s distance—literal and metaphorical—from the source of that noise.

As Koladza did in 1985 and at other times, those who dismiss the disturbance often compare piston-engine aircraft to the sound of a truck going by, at least in terms of decibel level at that moment. But that’s an inadequate comparison: Piston-engine propeller-driven aircraft create sound waves and vibration from both their engines and propellers that are very different than what’s produced by a passing truck. The noise of a fast-spinning aircraft propeller—something rarely if ever located on the front of a truck—by some estimates accounts for half the decibel level of the noise from an overflying plane. But that doesn’t capture the nature of the vibration or its broad acoustical effect.

From the air, that sound and vibration also covers more area: At the relatively low altitudes where most general-aviation aircraft fly, their sound impacts a much wider swath of people and properties on the ground than the proverbial “truck speeding down Route 71 near the airport.”

A recent Congressional Research Service review of airport noise regulations noted criticism from acoustics experts who argue that using only decibel-level thresholds “may not be an accurate indicator of how an individual or a particular community responds to aircraft noise and, therefore, it could be overly simplistic to rely solely on this threshold for regulatory purposes.” And in 2018, legislation funding the FAA asked the agency to begin examining other metrics for measuring noise and its impacts.

For decades, a host of studies have also documented the detrimental health impacts from aircraft and other noise, finding observable impacts on cardiac health in those who live near airports or who are subject to excessive noise. But the results are complicated, and aircraft noise discussions—which today often use language like “community annoyance” and “exposure-response curves” and “day-night average sound level”—are not always easy to decipher. But past studies have shown that the response to aircraft noise is more pronounced than annoyance from road traffic or railway noise. And children exposed to aircraft noise at home or at school suffer from measurable negative effects on reading comprehension and math skills and can show memory impairment.

There are also more personal factors that influence how people respond to noise. Those living in quiet, rural areas chose them as a place to live and have certain expectations. And when airports—and in the case of Great Barrington, flight schools—get noticeably busier, the change is no doubt more easily noticed in previously quiet areas than it might be in more heavily urban areas with many sources of sound disturbance.

But even in less-rural areas, substantial increases in airport activity and noise can lead to legal action, just as it has in Great Barrington. Homeowners near Rocky Mountain Metropolitan Airport in Superior, Colo., have sued over noise violations they say are the result of a dramatic increase in the amount of pilot training in recent years. (CBS News reported on a backlash against neighbors who complained that included online harassment; others who spoke out were doxxed, with their personal information shared online.)

Residents of Boulder, Colo. have raised similar complaints about large increases in piston-engine aircraft traffic that one resident told Boulder Weekly sounded like “having a lawn mower flying over your house all day.” Despite the “passing truck” comparisons, pilots are well aware of the different nature of the sound their aircraft create and how that sound travels. In Boulder, a court hearing in one lawsuit against a flight school included testimony that one of its pilots, upset over a neighbor’s noise complaints, purposefully circled her house in a way to maximize the disturbance, “descend[ing] in a props forward condition, meaning propellers in a fine pitch condition which yields higher noise,” according to testimony from another pilot who was in the plane. (The judge ultimately sided with the flight school.)

Different views of aircraft noise

The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA), which represents 300,000 pilots, advises in its noise-abatement guidebook, “A sound you love, like the drone of a piston airplane, may be an irritant to others.” It pointed out the obvious: “Whether a sound is pleasant or a nuisance depends on the listener’s associations with that sound.” Thanks to that power of association and selective adaption, some people don’t notice if a piston aircraft flies nearby once a day or 20 times an hour. Others, one pilot told me, hear the sound of a propellor aircraft as nails-on-a-chalkboard when he doesn’t even notice there’s a plane going past. Regardless, the AOPA guidebook advises in its first section, “It does not matter if the airport ‘was here first.’ Now that it has neighbors, their concerns must be taken seriously.”

When I asked Sean Collins, who has been AOPA’s eastern regional manager for the last decade, about noise and airports, he was blunt. “Noise and environmental concerns are the number one concern that we see at airports like Great Barrington,” he told me in January. “That’s probably the primary issue that we see across all airports, at least when issues arise.”

He said it’s common for airports to be in residential areas; homes are often in the area before an airport arrives and others are built afterwards. “Candidly, having homes around an airport is not in the best interest of the public or the airport. [But] we can’t go back and change paths.”

He suggested that, historically, many communities and local governments didn’t do enough to keep homes and development away from airports—not a surprising perspective from an aviation-industry advocate. “If you have homes next to an airport, you’re going to have noise complaints. If you don’t have homes next to an airport, the likelihood that you’re going to get these really bad noise complaints diminishes greatly.”

In some communities with municipally owned airports, he said, there may be agreements or at least real-estate disclosures that include acknowledgement of an airport nearby. “A lot of municipalities that own their airports do that. But a lot of communities with a privately owned airport [like Great Barrington] don’t,” he said.

Collins highlighted the challenge created by federal pre-emption over airspace and flight rules. That means an airport’s noise-abatement procedures can only be voluntary, he said. “So it’s incumbent on pilots to be good neighbors, and we espouse that as an organization.” He also pointed to the Airport Noise and Capacity Act of 1990, a law that transferred regulation of aircraft noise from localities and states to the FAA. But he said flight schools can better manage complaints by sending student flights to more sparsely populated areas, moving training to different places on different days—perhaps with defined quadrants and schedules that are shared with local communities—and providing data on how much takeoff-and-landing practice, for example, may be happening elsewhere as part of ongoing noise-abatement efforts. (These and other ideas are explored further in an upcoming installment of this series.)

Lori Bashour, one of the organizers of the Citizens Committee to Save the Great Barrington Airport, told me in November that she sees the airport as a vital community resource, and that living with some disturbance from aircraft noise is no different than other inconveniences we accept as part of living in a community of people with diverse interests. She lives about a half-mile west of the airport with her husband, longtime pilot and Berkshire School aviation-science instructor Michael Lee.

Bashour said when she’s at home and planes are flying over frequently, she takes it in stride. “So we’ll be sitting outside, and we’re talking, and a plane comes by,” she explained. “We just have to pause our conversation for, literally, like five seconds,” she told me. “But I just look up and go, ‘I wonder where they’re going today.’ You know, it doesn’t have to be an issue.”

That’s clearly not a view held by everyone near the airport or further afield, particularly when there’s a lot of flight activity. During the public-comment portion of a recent airport hearing, neighbors voiced the same concerns they did when the board turned down the airport’s special-permit application in 2020. Joanne Cooney, a Hurlburt Road resident, said she “loved having that little airport” but preferred it the way she said it was. “From my experience, it went from a sleepy little airport to a lot of activity.” Countering the idea that it’s only wealthy second-home owners or recent arrivals who have complaints, she told the board, “We’re not wealthy, we’re retired civil servants and social workers.”

While neighbors complain primarily about traffic intensity, the airport has long suggested the unchangeable length of its 2,579-foot runway limits any growth or expansion. But even without a change in runway length, operations have increased substantially in recent years, with the flight-school a primary source of complaints. “The flight school is the elephant in the room,” said Mike Peretti, a lifelong airport neighbor on Seekonk Cross Road, when presenting testimony to the board in late February. He said the town needed to find “a grand compromise,” and his suggestion was that the flight school not operate on Sundays.

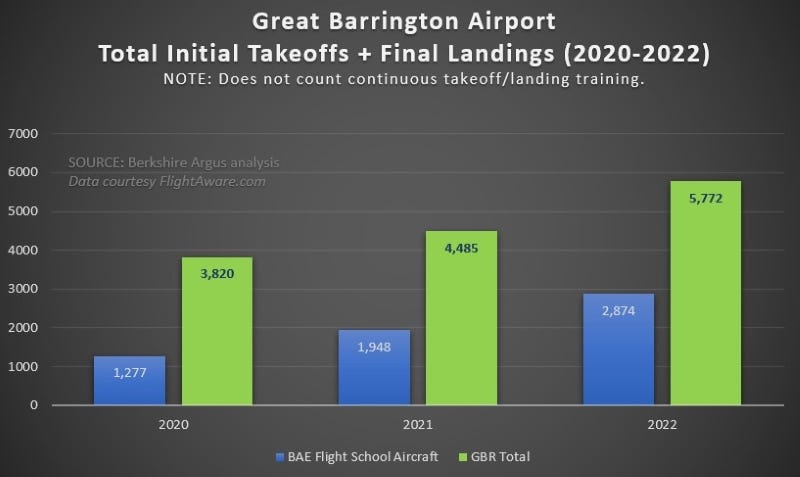

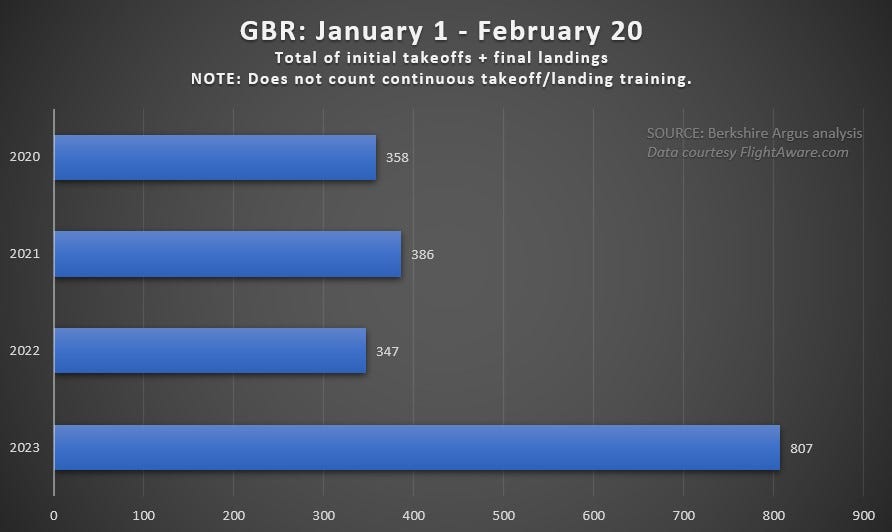

An Argus analysis of actual airport flight data from 2020 through February 2023 documented the increase that began a few months into the pandemic and continued through the following few years. Traffic associated with BAE’s flight school increased by 125 percent from 2020 to 2022. There was also a further 133 percent increase in overall traffic during the first six weeks of 2023 over the same period last year. (Airport attorney Dennis Egan told the Selectboard last month that the Argus analysis of data from FlightAware was “nonscientific.”)

Be like Sully?

When I began this project last summer, one of the first people I spoke to was Kathleen Bangs, a former airline pilot and flight instructor who today is a writer and the spokesperson for FlightAware, the flight-tracking company. Over the last couple of years, she’s been a constant presence on news programs, providing information about challenges in commercial air travel as pandemic restrictions were lifted and travelers faced delays, canceled flights, and extended aviation-system disruptions. (DISCLOSURE: FlightAware provided, at no charge, some of the flight-tracking data used in the Argus analysis of flight operations at GBR.)

Bangs is an unabashed fan of small planes flying overhead. “The sound of a reciprocating engine propeller is music to my ears, but it may not be to everyone,” she said. (During our interview, Bangs also conceded that she “likes the smell of jet fuel in the morning,” so she may not be the median test-case.)

At one time, she served on airport commissions for both a large municipal airport as well as a small general-aviation airport, both of which opened her eyes to what airport neighbors experience. “I used to not really notice airport noise until I started working at the commission, [and] looking at it from different people’s perspectives,” she said.

She described a recent visit to her daughter’s home in southeast Washington state, where she lives near a small airport. “All day, on a good day, there are little twin-engine airplanes doing traffic patterns,” she explained. “And I love it, it’s relaxing, I enjoy seeing them, I enjoy hearing them.” But she understands the reaction others have to a busy day in the skies above their homes. “I know they might consider it noise and a nuisance and a risk. I totally understand that.”

Like Collins, Bangs said flight schools will try to spread traffic around to different areas on different days. But as a former flight instructor, she said she knows that instructors often get familiar with certain areas and use them repeatedly. That’s because they know the features of an area are appropriate for certain drills they want to work on with their students.

Bangs has a sober view of the conundrum; pilots need to be trained, after all. “To some extent, people have to realize they don’t own the airspace above them,” she told me. “Everybody wants transportation. Everybody wants convenience. Everybody wants to be able to get to an airport and have a nonstop flight, but they just don’t want it anywhere near them.”

Still, Bangs understands where complaints come from, comparing an increase in flight operations to the arrival of jet skis on a once quite lake. (There was this very battle at Prospect Lake in Egremont years ago; a state law passed in 1989 now bans jet skis from lakes smaller than 75 acres.)

But like others, she suggests taking a broader view, particularly on things like the engine-out drills that can unnerve those on the ground. “Rather than look at it as a negative, people should try and think, ‘Hey, you know, even Sully learned somewhere,’” she said, referring to Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, who famously landed a damaged US Airways Airbus A320 jetliner in the Hudson River in 2009, saving all 155 people on board.

Sullenberger learned to fly at a small, private, grass airstrip in the late 1960s from L.T. Cook Jr., an instructor who by then was working mostly as a crop-duster but occasionally took on a student. They were in rural North Texas, near an Air Force base whose jets screaming low over Sullenberger’s home sparked not complaints about noise, but rather, his interest in becoming a pilot.

Bangs said Sullenberger no doubt had engine-out instruction over someone’s open fields. “I assure you, he had an instructor in the seat next to him, you know, ‘Shut down that engine, what are you going to do now?’ And that stuff stays with the pilot, their earliest lessons.” (After Sullenberger’s famous water landing, he received a letter from Cook’s widow: “L.T. wouldn’t be surprised,” she wrote, “but he certainly would be pleased and proud.”)

Benchmarking and the battle to establish the facts

The Selectboard is now weighing all of these various perspectives, and there’s little question that its focus is on what level and type of activity is appropriate for an airport located where this one is. Its March 13 hearing focused on a few key issues: whether special-permit conditions proposed by the airport were meaningful or enforceable; how future owners and Selectboards might view any special permit approved this year; and perhaps most importantly, how to establish—or “benchmark,” as Vice Chair Leigh Davis put it—the current level of operations at the airport.

That last item is essential to even attempt to craft something that delivers what Egan has told three different town boards since late January is the airport’s single request: A special permit recognizing it as an “aviation field” under the zoning bylaw and that limits its activities to “what you see is what you get.”

That’s why it was surprising to see Egan repeatedly push back on efforts to establish those facts. Not only because it’s central to what the airport is requesting, but also because the lack of clarity around the intensity of operations at the airport has fueled the contentiousness of 1990, 2017, 2020, and now in 2023. It’s also the central issue in the Land Court case.

And, importantly, it was specifically highlighted in the Selectboard’s 2020 findings when it rejected the airport’s prior application: “The Selectboard finds that growth at the Airport beyond its current level of use and type of operations, including types of aircraft, could further detract from the rural residential/agricultural character of the area. This would be in direct conflict with the Town’s Master Plan,” they wrote. It pointed to a key line in that governing town document: “The Master Plan specifically states, relative to the Airport, that ‘any activity, growth, or development here must be regulated to protect the town’s water supply, and to ensure uses are compatible with residential and agricultural neighbors.’”

Given the documented increase in flight operations and flight-school activity at the airport since those findings were written, it presents a challenge for BAE. But rather than engage on the subject in the search for a durable, lasting solution, Egan has pursued a curious strategy on behalf of his client: Deflect efforts by board members to clearly establish the airport’s current activities.

‘Specificity is very important’

Egan had suggested the airport was eager to provide that information. “I just want to be clear, because I know the reputation attorneys have and sometimes it’s well deserved,” he said early in last month’s hearing. “I’m not trying to play hide the ball. Some of the first words out of my mouth before this board were ‘what you see is what you get.’ If the board wants to drill down into that and ask specific questions, we’re happy to answer those questions.”

To enshrine current activities, which would be the basis for evaluating future approvals the board might consider for new facilities or increased operations, Town Counsel David Doneski told the board several times that specificity is vital. “You’re being asked to approve what currently exists on the property and the associated activities as they’re being presented to you,” he said.

Davis, who pursued the question of benchmarking several times, said that any aviation field special permit would enshrine “the new normal.” She asked Doneski, “Do we have to specify what exists now, so we have a place to start?” He replied, “It would be my recommendation that any special permit be as particular as possible regarding what is existing. The essence of the application is to have a special permit issued to cover what the existing operations at the property are. So, specificity is, in my view, very important.”

Davis said she didn’t think the special-permit application provided that level of detail. “What we have in front of us I don’t think is sufficient … if this is to move ahead, we have to specify what exists now.” Later, she asked Egan, “Going back to data, and that we don’t really have a sense of how many flights are coming in … is that something that will be provided, so we have a sense of where we are now versus any increase in flights?”

Egan said that counting flight operations “is not required at general-aviation airports and we don’t do it”—something he repeated several times.

While it’s true that the FAA policy circular relevant to reporting flight operations is, according to an FAA spokesperson, advisory, nearly every public-use airport in the United States, including the one in Great Barrington, reports that information. During an airport’s mandated triennial inspection, which covers a host of safety and other issues, airport management provides data to an inspector—contracted through MassDOT but collecting information for the FAA—on the previous 12 months of flight activity. That data is extremely accurate in the case of towered airports and represents some combination of actual and estimated totals for other general-aviation airports, depending on their processes and any technology they utilize.

While Egan told Davis that the airport doesn’t count flights, at a September 21, 2020, public hearing on the airport’s previous special-permit application, he said it does. When an attorney for airport neighbors highlighted the airport’s reported 2019 total flight operations of 17,520 per year—the number BAE included in its 2020 special permit application—Egan first claimed the airport’s own number was inaccurate. He said, incorrectly, that the data was “an estimate provided by the MassDOT [Aeronautics] Commission.” He then went on to say, “The fact of the matter is that the takeoffs and landings that we submitted [in a supplementary letter] are based on [an] actual count and are not estimates. And those are updated.” He told the board he felt it was important to provide the facts “because they matter, and they are material to the issues at hand.”

In that 2020 supplement, Egan wrote, “Based on records provided by BAE, GBR averages 10-15 takeoffs and landings per day on weekdays, and 30-35 takeoffs and landings per day on weekends.” That would translate, on the high side, to 7,255 takeoffs and landings per year. In its submission to the FAA last summer, BAE said there were 12,275 flight operations over the prior 12 months.

During the Selectboard special-permit-hearing process in 2017, there was similar discussion of the level of operations. In its 2016 flight-operations submission to the FAA, BAE put the total at 41,610, or 114 takeoffs and landings per day. Asked specifically about that number, Solan told the board that it was “probably fair.” He also told them that he didn’t expect the airport’s activity would increase much. “[We’re] not going to get much more than we’re getting right now,” he said. “One hundred and fifty [a day] at most. On a good day, maybe 200.”

The Virtower solution

In fact, the airport could easily deliver quality data on flight operations to the Selectboard. As reported in part three of this series, in 2014 MassDOT provided the airport with technology known as G.A.R.D. that can count flight operations. But Solan told me they don’t use it for that purpose.

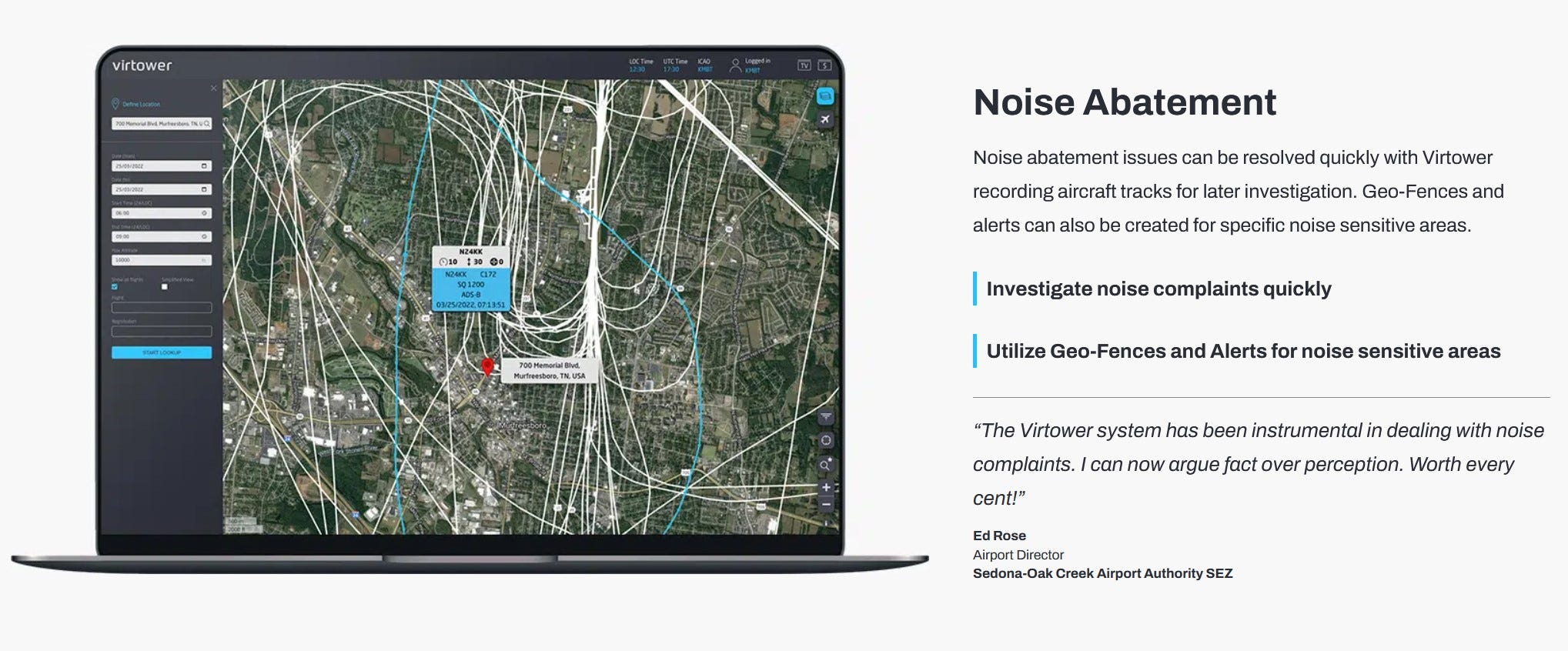

And today, hundreds of airports use technology at modest expense that provides precise flight-operations data. And it’s not only because they want to report accurate information for their FAA master record, but because it’s also useful for good airport management. Nearly 150 general-aviation airports use an affordable system called Virtower, a hardware-and-software solution that accurately counts all takeoffs and landings—including the continuous takeoffs and landings common during a flight-school lesson. It counts operations by planes outfitted with the now-common ADS-B transmitter and also many from the shrinking number of planes that still only have an older transponder.

With built-in geofencing (establishing zones on the equivalent of a Google Map), Virtower can also confirm which aircraft are based at a field, when aircraft are parked at fuel pumps, and completely track flightpaths of student flights and others like those seen on FlightAware. The cost? About $500 a month for small airports like GBR.

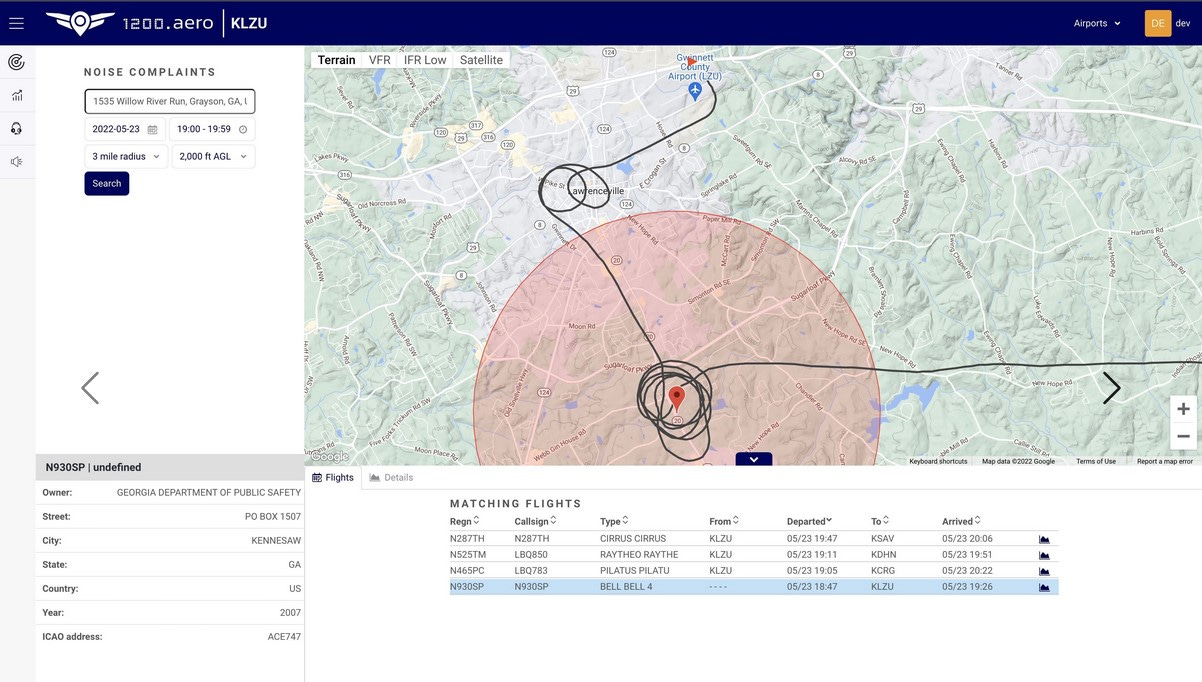

Because it tracks nearly all flights, it can be an enormously useful tool for investigating noise complaints, like when a pilot may be violating local flight patterns or the airport’s noise-abatement recommendations. That can only benefit an airport and the community in which it operates by providing actual information rather than just accusations and conjecture. Indeed, another product offered by a company called 1200.aero said its data analysis allows “research[ing] low-flying activity by street address on a given date, approximate time, search radius and maximum altitude.”

Utilizing a system like Virtower could be an important advance for Great Barrington. When I asked Rick Solan recently about how neighbors and the town will be able to enforce the conditions of any special permit, he said they’ll just have to trust him. “I’ll be under a microscope,” he said. But Virtower or a similar system would provide a version of Ronald Reagan’s directive to “trust but verify.” It would create a more fact-based, publicly accountable process that removes the fog of uncertainty that has fueled decades of distrust and contentiousness around airport operations and noise abatement.

Expertise to evaluate the facts

It’s not just clarity around flight operations that would help; the Selectboard also needs expert evaluation of all the information being presented. Board Chair Steve Bannon told me in December that the board wouldn’t hesitate to ask for expert advice as needed. Indeed, the board can engage consultants or other experts as it evaluates an application—and the cost is passed on to the special-permit applicant. But to date, the board has not sought outside expertise on questions of flight operations, aviation-related law, environmental questions related to leaded fuel or state regulations, or on any other matter.

It would be useful to ensure Selectboard members can fully vet what they’re being told. For example, when asked about BAE’s qualification as a MassDEP-registered “very small quantity generator” (VSQG) of hazardous waste, which exempts the airport from some groundwater-protection-bylaw requirements, Egan repeatedly ignored the key part of state regulations: A VSQG is not permitted to generate more than 27 gallons of waste oil per month. As detailed in part four of this series, that’s a separate requirement from the on-site waste-oil-accumulation limit that Egan has highlighted. Indeed, if the total amount of hazardous waste accumulated on site was all that mattered, and there was no monthly generation limit, a facility could fill a 55-gallon drum daily and have it removed each night and remain under the total-accumulation limit.

There are other details: Egan told Davis that the airport would share information on its waste-oil production and disposal with the Selectboard on the same schedule that it provides that information to the state. But there are no required state filings of those details: According to a MassDEP spokesperson, hazardous-waste producers must keep detailed records of production and disposal of waste oil for three years, but those records are only shared with MassDEP if the agency conducts an audit—which it hasn’t done at the airport since 2014.

Bylaw provisions still unenforced

As with bylaw enforcement on matters like hazardous-waste generation, Doneski’s recommendation to fully benchmark current airport operations—essential to crafting workable special-permit conditions—will only be useful if the town is prepared to enforce the conditions. Going back to 1932, town officials have consistently failed to enforce zoning provisions that apply to the airport, which certainly raises reasonable concern about the future.