In the final installment of THE AIRPORT, a detailed history of Great Barrington’s zoning bylaw and its role in the past, present, and still unknown future of the town’s 92-year-old country airport.

∎ ∎ ∎

Early one evening in July 1950, Walter J. Koladza—the test pilot, flight instructor, and owner of the Great Barrington Airport—appeared at the weekly meeting of the town’s Board of Selectmen. Standing in front of three men long dubbed “the town fathers” for their municipal authority and broad, community-wide influence, Koladza shared news that today, amidst years of neighborhood turbulence over activities at the airport, seems laughable: He announced plans to build a stock car racing track on his property.

The new speedway would be an eighth of a mile in diameter, he said, creating a short-track racing oval. At the time, similar venues were attracting crowds all over, including nearby Hudson, N.Y.; Bennington, Vt.; and Albany to the west and Springfield to the east. Koladza promised the track “would be placed so it would not cause congestion or be an eyesore to the area,” according to minutes of the meeting.

At the time, zoning had been in place in Great Barrington for nearly two decades. Koladza, who bought the airport in 1945, certainly knew that his 90-acre property—a significant commercial use in a residential neighborhood—was considered “preexisting nonconforming” under the zoning bylaw. That meant any change or expansion, under which stock-car racing surely qualified, would need a zoning change advanced by the Planning Board, a permit or variance from the Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA), and possibly the approval of town voters. But Koladza, and the airport’s owners before him, had rarely bothered with those formalities.

The airport was established in September 1931, less than a year before zoning was implemented. Its founders and early owners were a who’s who of Great Barrington’s business and municipal elite: Koladza purchased the airport from James F. Tracy, a popular chairman of the Board of Selectmen who himself ignored zoning restrictions and permit requirements as he developed the property and substantially expanded operations during World War II. And as the Great Barrington community learned recently—particularly via zoning-enforcement litigation ongoing in state Land Court and from testimony presented during a recently concluded special-permit process—Koladza would spend another five decades ignoring municipal rules that others in town could not so easily sidestep.

On that warm summer evening, the selectmen said they would study the race-track proposal, promising to review any legal requirements with the town’s counsel, a local attorney and future Southern Berkshire District Court judge named George R. McCormick. “Mr. Koladza was told the zoning laws would have to be checked to see if a venture of this type would be allowed there,” the weekly Berkshire Courier reported.

Koladza returned a week later, perhaps expecting the usual strings had been pulled and winks and nods exchanged. But the selectmen told him the Planning Board would have to be consulted. Still, they said they had no issue with stock-car racing at the airport if there was no gambling and “noise was kept to a minimum,” according to news reports. At the time, it was not uncommon for the most powerful board in town to telegraph its opinion to direct the actions of other boards and municipal officials—especially when they were appointed or hired by the selectmen.

In response, Koladza promised the preposterous: “The noise made by the racing cars would be no more objectionable than that of trucks passing through” the neighborhood, he told the board, a surprising claim about the sound of automobiles circling a small track for hours at a time. Indeed, nearby stock-car events that year featured “endurance” races of 50 miles, which would be more than 100 times around Koladza’s proposed circuit.

If his metaphor for comparable sound levels rings a bell, it’s because the same “no-louder-than-a-truck-passing-by” argument has long been made by those who say there’s little objectionable noise at or near the airport from its—in recent years, substantially increased—aviation-related operations.

He also assured the selectmen that airport neighbors were on board with his plan. Well, at least one: According to the Berkshire Courier newspaper, “[Koladza said] he inquired of his nearest neighbor if he had any objections if a track were established and said his neighbor told him he did not.”

Another airport abutter, Clarence A. “Nick” Parrish—an early aviator and longtime flight instructor at the Canaan, Conn. airport—dropped by while Koladza’s proposal was discussed. Parrish, who would appear before the board again in 1964 to strongly oppose another Koladza plan to monetize the Egremont Plain property with development unrelated to aviation, asked about the racetrack application. Told there was no formal proposal, the Courier amusingly reported what happened next in the succinct, matter-of-fact news-writing style of the day: “Mr. Parrish said he had nothing to say and left the meeting.”

Even an airport-friendly group of selectmen knew that a racetrack at the airport couldn’t simply be waved through. It would require, at minimum, a public hearing. Koladza would have to request a zoning variance or begin the process to rezone the property, they told him. But he never did, no doubt familiar with the heated town battles that regularly played out at those hearings and at related town meetings—often for proposals far less significant than stock-car racing in a residential neighborhood. With big plans for his privately owned airport as aviation exploded across the country, and aware of a zoning status that could stand in the way, he likely didn’t want the spotlight.

Zoning ignored and the recent troubles

Indeed, that may be why Koladza never, with one exception, sought zoning approval or even building permits for construction projects or expansion of operations during the 60 years he owned the airport. (Koladza died in 2004.) Other than in 1990, when a battle over incessant, weekend-long noise from planes towing motor-less gliders to altitude first revealed the airfield’s status to many town residents, Koladza successfully remained under the zoning radar.

The failure of generations of municipal officials to act as the airport grew—including an increase in flight operations that neighbors have complained about since at least 2017—is what led to a zoning-enforcement request made by a group of neighbors in November 2021. When the town’s zoning-enforcement officer and ZBA both dismissed the complaint—the latter with what the neighbors’ attorney, Thaddeus Heuer of Boston’s Foley Hoag argued is a legally questionable analysis—the matter moved to state Land Court on appeal.

The strength of their case—which three plaintiffs and other supporters have said is about reining-in growth at a small country airport, not shutting it down—is what led to the airport’s successful third application for a special permit. If it survives any appeals and an upcoming decision by Land Court Chief Judge Gordon H. Piper, that permit will erase decades of zoning violations and clear the way for operations to continue at least at the level reached in recent years.

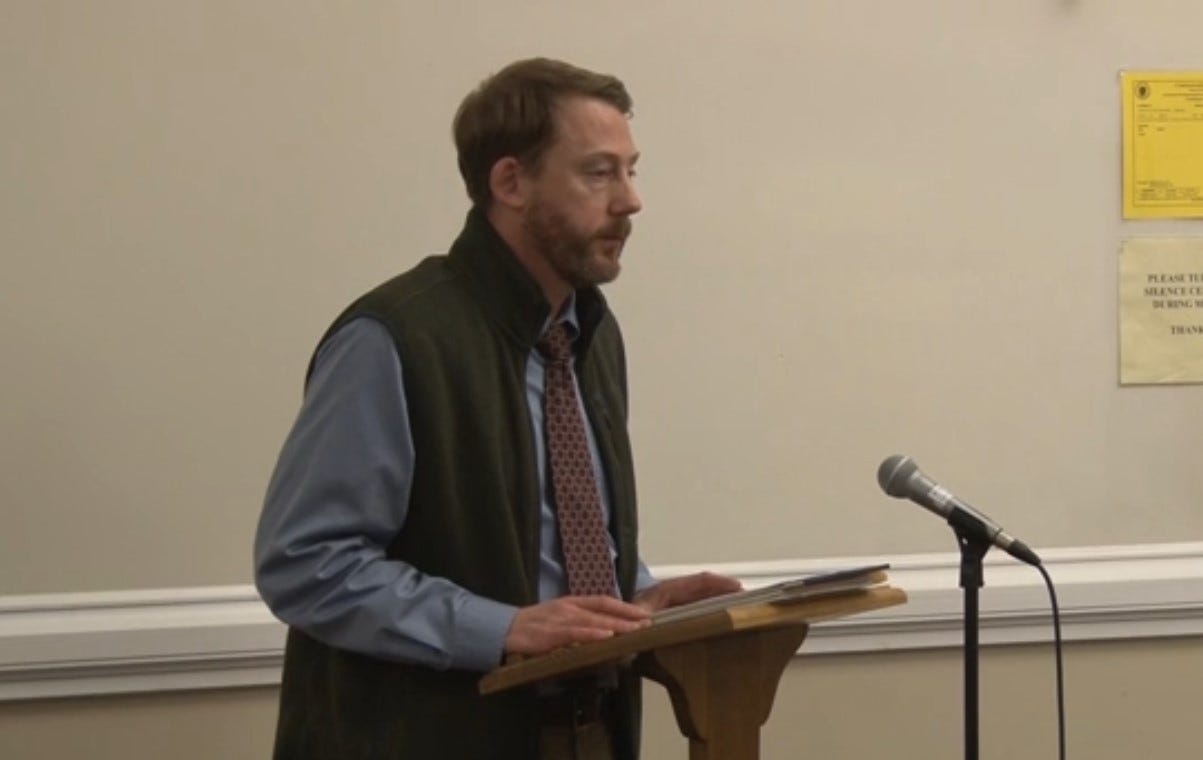

But the special-permit process also produced findings and conditions that, its critics say, do little or nothing to meaningfully address the concerns raised by neighbors and others since the airport owner, Berkshire Aviation Enterprises (BAE), first went before town officials in 2017. Ed Abrahams, the now-former Selectboard member who was the only ‘no’ vote on the permit last month, told his four colleagues that, as constructed, the special permit is largely unenforceable and may do the opposite of what proponents claim: Lacking metrics about airport operations today—and without mandating the use of widely available technology that airports use to count those operations—it removes any hope that the town can enforce the agreement or meaningfully influence what happens at the airport going forward, Abrahams said.

He also argued that no facts had changed since the board unanimously rejected the airport’s previous application in 2020—though Selectboard Chair Stephen Bannon and Vice Chair Leigh Davis, who both opposed a special permit then, voted to approve it last month. (Bannon at one point during this year’s hearings told Abrahams that one change from 2020 “is the Land Court case.”) Abrahams also argued that the board’s decision had to comply with the zoning bylaw’s specific legal requirements, which called on the airport to demonstrate that its operations weren’t objectionable and wouldn’t become more so in the future. That was something Abrahams said the airport’s application didn’t do.

From that point of view, granting a special permit with unenforceable conditions may be the same as 90 years of town officials looking the other way. To the frustration of airport critics, it looks like municipal business-as-usual. Several told me it was the expected result of a Selectboard hearing process that, in contrast to earlier airport hearings, restricted public comment after the first day of hearings, even as key conditions were crafted.

But airport proponents say that BAE has done what’s required: Even if it skirted zoning in the past, the airport has now acquired official recognition as an “aviation field, public or private” under the town’s bylaw—something they point out the neighbors’ attorney specifically said in Land Court could address the zoning complaint. The special permit was approved 4-1.

Despite zoning limits, airport expansion races ahead

After abandoning his plan for stock-car racing in 1950, Koladza’s airport grew rapidly in plain sight. He expanded charter and air-taxi services, kept up a busy flight school that profited from post-Korea G.I. Bill funding to train veterans as pilots, added new hangars and flight-school classrooms, and told the press that BAE was growing by at least 10 percent annually.

In a June 1956 article, Berkshire Eagle reporter A.G. Rud described Koladza’s progress: “In those 11 years, all the airport’s activities have expanded steadily, and nowhere is this more noticeable than in charter flying,” Rud wrote. “When Berkshire Aviation started in 1945, one charter flight a week was considered a good average. Now, in a busy season, eight in one day is not unusual.” And the little country airport was building a sterling reputation: A journalist writing in the widely read Flying Magazine dubbed Great Barrington’s “the friendliest airport in New England,” a slogan still used in its marketing today.

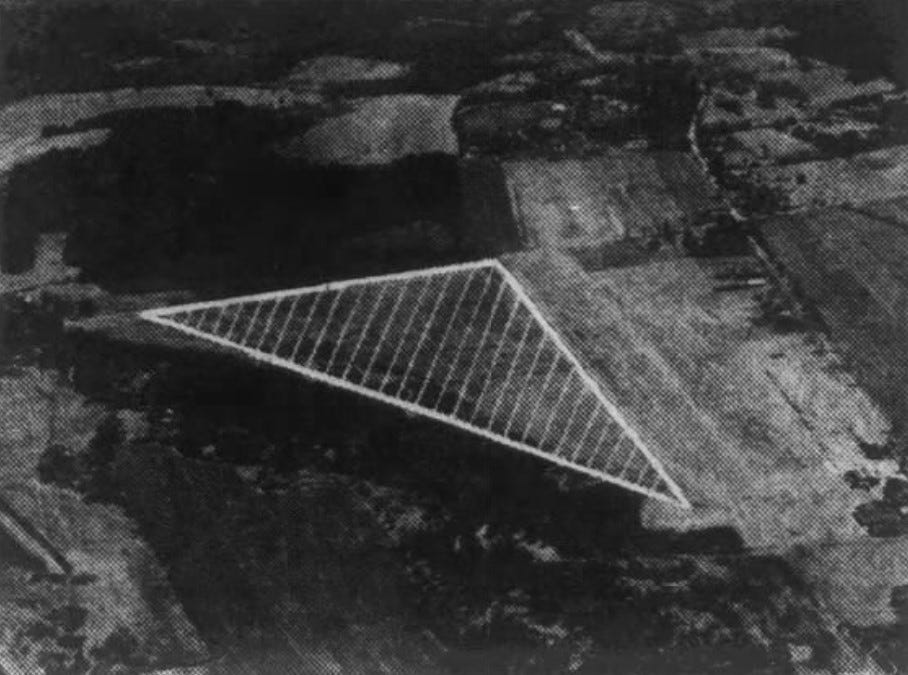

The following year, with commercial aviation expanding across the region, Koladza set his sights on a crucial upgrade: transforming the airport’s half-mile, east-west, grass landing strip into a modern runway of compressed oil-and-stone. (It would be upgraded to a fully paved runway in the late 1960s.) He told a reporter for the Greenfield Recorder that the improved runway would enable larger planes to land in Great Barrington so he could “keep up with other [air]fields in the surrounding area” and “maintain the charter and rental services.” Like the airport’s other construction projects, no building permits or zoning approvals were sought or acquired.

How could such a large project, which promised further increases in the airport’s level of use, be undertaken without any town permits or approvals? After all, battles over zoning rules and campaigns for variances, which began just weeks after Great Barrington’s first permanent zoning bylaw took effect in 1932, had continued apace into the 1950s.

Indeed, a review of decades of ZBA files and related news coverage reveals how even small changes to the use of residential properties for business purposes required all manner of very public, zoning-related hurdle-jumping. Homeowners who sought to open curio shops, hair salons, and small general stores in their homes filed applications with town boards, gathered signatures on supportive petitions, and often brought spot-zoning requests to well-attended and sometimes raucous special-town meetings. Not to mention more significant battles over frequent-but-not-always-successful efforts to establish funeral homes, restaurants, and other businesses in residential neighborhoods.

That’s not to say things didn’t regularly happen in Great Barrington that violated both the spirit and letter of the zoning bylaw. Particularly in the 1930s and ’40s, the ZBA was asked to approve variances for things done without permission and to overturn enforcement actions taken by the building inspector, which it often did. But the airport was always treated differently on matters both large and small; its owners simply ignored the bylaw without repercussions.

Examples of those smaller matters included “The Airport Bird Shop,” a retail pet store launched by Koladza’s wife, Louise, that sold parakeets and exotic birds, yet never secured a zoning variance. By the mid-1950s, the airport established “The Helmet and Goggles Snack Bar” in its basement, where Koladza also offered overnight accommodation for pilots in a couple of adjacent rooms—none of which was allowed in the airport’s residential zone. Today, an updated zoning bylaw specifically prohibits hotels, restaurants, and a long list of other activities and uses in the airport’s R4 residential/agricultural district.

But as the ongoing litigation that spurred the airport’s latest special-permit application made clear, it was the unapproved and substantial increase in aviation use, over decades, that was the primary and most significant violation. The strength of the neighbors’ zoning-enforcement case is what put the airport in front of the Selectboard again this year, arguing its “existence” was at stake without a special permit and leading to a high-profile “save the airport” campaign. Which, if true, arguably conceded the merits of the neighbors’ zoning argument.

The 1957 runway project is one example of how municipal and business interests merged in ways that allowed the airport to skirt zoning requirements. The local company hired to handle design, construction, and project management was Berkshire Engineering Co. Its founder and president, William F. Barrett Jr., was also a pilot, and according to news reports, he personally oversaw the work at the airport. But he was not only a construction engineer and a pilot: At the time, Barrett was also a Great Barrington selectman.

There were other financial connections between the runway project, the town, and business and municipal leaders. According to the Recorder’s detailed profile of the airport, Koladza said the total cost of the new runway was around $15,000, or more than $160,000 in today’s dollars, and revealed that some amount was paid to the Town of Great Barrington—but not to cover fees typically associated with building permits. Instead, money changed hands so the airport and Barrett’s construction firm could use town-owned heavy-construction equipment to build the half-mile runway, the Recorder reported. But there’s no mention in local news coverage of town government in 1957 that details that arrangement—in those days, every selectmen’s meeting was covered in detail. Today, according to town officials, the Selectboard’s minutes from 1957 are missing, so they can’t be reviewed for any discussion among board members or the amount of income to the town.

The push for zoning in the 1930s

Zoning was first implemented in Great Barrington with approval of a temporary bylaw in March 1931 and a more extensive, permanent set of rules a year later. As with other municipal projects of the era, the driving force was the Southern Berkshire Chamber of Commerce, which, as reported in part two of this series, operated essentially as an arm of town government. Its committees, including one established with 16 members in April 1930 to study zoning, were filled to overflowing with the town’s business elite. Many Chamber members also served in various municipal roles, elected and otherwise. And a number were shareholders and directors of Berkshire Airways Inc., the company formed in 1929—out of another Chamber committee—to acquire the airport property and begin its development.

By the end of 1930, the Chamber’s zoning committee had engaged the help of a Boston-based, state-government-affiliated planning consultant, Edward T. Hartman. At that point, around 70 communities in the Commonwealth had adopted some form of zoning bylaw, following passage of a state law a decade earlier that empowered towns to create planning boards and establish zoning rules. Hartman urged the committee to push for a temporary zoning bylaw and allocate $2,000—about $40,000 today—for development of a detailed bylaw and zoning-district map.

Hartman was one of the more fascinating, influential, but still little-known state officials of the era. Born in 1876, he was an academic and activist who published papers and articles about housing policy and urban planning. He spent decades as the outspoken secretary of the Massachusetts Civic League, formed in 1899 to advance social-welfare and community-development ideas and policies. He was articulate, prolific, and energetic: In 1923, during his first seven months as the state’s newly hired “Visitor to City and Town Planning Boards,” a consulting position created inside the Department of Public Welfare, he held more than 70 meetings with local officials across the Commonwealth to champion the benefits of zoning.

‘The tumors of industrialism’

As Hartman saw it, the need was urgent. The rapid spread of both automobiles and taller, steel-construction buildings going up in town centers had already led to explosive, willy-nilly growth in communities statewide. One notable bogeyman, Hartman suggested, was the gas stations multiplying along roadsides and in residential neighborhoods where they spoiled views and lowered property values. In his view, sensible town planning paired with zoning rules to guide development would protect local economies, preserve property values, improve living conditions, and ensure quiet residential neighborhoods were not overrun by commercial enterprises that should be in business and industrial districts.

Hartman was forceful and direct, mincing few words in his speeches and writings. In a 1928 state report, he warned that “[commercial] encroachments are spreading across the land … this applies particularly to the large areas without zoning, but there is much of it in some zoned places, where special interests urge that the tumors of industrialism and commerce must spread, and spread, until all the territory of the state is covered, at least to an extent that leaves no proper home districts.” A true believer, he laid blame widely, often with little sympathy for town officials who had to juggle competing local interests: “Citizens, politicians—the tools of special interests from both these groups—permit and even aid in spreading these encroachments over ever wider and wider areas.”

Throughout 1931 and 1932, Hartman’s efforts to rally support for zoning in Great Barrington were covered exhaustively in the Eagle and Courier. Indeed, as the town’s nascent planning board advanced the temporary bylaw to voters in 1931, Hartman was ubiquitous. He contributed long explanatory articles to the papers and gave countless speeches at gatherings of Rotary members, the Chamber of Commerce, and other organizations. His activities were reported in detail—particularly by the Courier, which championed the new rules and would later criticize the ease with which variances were granted and spot zoning approved by boards and town-meeting voters.

After approval of the temporary bylaw, Hartman was hired to help write the permanent rules and continue his public advocacy. In a speech to the Great Barrington Rotary Club in September 1931, Hartman made his standard pitch. “Zoning is one law that protects the poor man as well as the wealthy,” he said. “When a poor man builds a home and puts every cent into it, this man is protected where there is a zoning ordinance.”

Creating a good quality of life for everyone in a community, he suggested, required ensuring that different uses were in their proper place. His metaphor was a house: “The sink and range are in the kitchen, and should not be in the parlor,” he told Rotary members. “In a town or city, industries should be located in one place, and the residential section should be in another.”

Hartman’s efforts had the flavor of a political campaign. Indeed, with his hand in zoning projects across the Commonwealth, he knew that nothing could happen without broad support in advance of a town-meeting vote—and afterwards. “Public understanding is essential to adoption by a town meeting, to compliance by the people, and to enforcement against violations,” he wrote in a 1931 state report.

In November 1931, as Great Barrington’s permanent bylaw neared completion, Hartman was the featured speaker at what the Eagle described as the “record-sized gathering of the season,” organized by the Housatonic Community Improvement Association. In front of a packed crowd of perhaps 200 people in Housatonic’s Forester’s Hall, he again argued that zoning “is as important for the working man as for the wealthy,” from those employed in real estate, insurance, and banking to the “plasterers and others [in] all trades” who would benefit from its protections.

His wordcraft and metaphors were creative and engaging; he was aware of the dry nature of zoning maps and bylaw text. When describing what he considered the scourge of roadside billboards and their threat to the Berkshires’ natural beauty, he said, “Billboards and scenery won’t mix any more than whiskey and gasoline, even though the gas is in the car the whiskey in the driver.”

The Eagle’s coverage noted that, after Hartman’s Housatonic speech, “The audience enjoyed a pancake supper through the courtesy of A.E. Gerard and Company,” a local grocery store, and that “Smith’s orchestra played for dancing following the repast when round and square dances were enjoyed until after 12 o’clock.” Whether a free meal and dancing late into the night were the draw for a speech about zoning is unclear. To be fair, though, Hartman’s other local speeches were well attended. But it’s also true that today, at least, engaging community members in the complexities of zoning can sometimes be a hard sell—not to mention the intricacies of zoning-related case law at the heart of the airport controversies. To wit: Chris Rembold, Great Barrington’s longtime planner and now also its assistant town manager, began a February 2018 presentation to the Select Board on proposed zoning changes with a wry preface: “Those of you who aren’t sleeping yet,” he said, “now you can go to sleep. We’re going to talk about zoning.”

Let loose the variances and spot zoning

At 1932’s annual town meeting, the permanent bylaw was easily approved with no debate. It created new residential, business, and light-industrial districts and established rules related to “use, construction, repair, alteration, height, location and area of buildings and structures and the use of premises in the town.” The Courier ran an editorial cheering the vote, noting “the designation of certain areas of the town as purely residential can only result in the stabilization of the property values in the area [where] encroachments of a harmful nature are prohibited.”

But adjusting to the new rules, and ensuring their fair and equitable enforcement, soon proved a challenge—one common across the state. And the Courier’s editors warned as much: “The various officials responsible for the administration of the new bylaw will likewise be confronted with many opportunities to interpret its provisions,” they wrote. “Upon the judgment exercised by the [building] inspector and board of appeals rests the success or failure of the new by-law.”

Indeed, even as Hartman spoke to Great Barrington residents in advance of the vote with optimism and encouragement, elsewhere he complained bitterly about myriad ways “seekers after special privilege” were undermining zoning. While he described “credible, even excellent, improvement and enforcement of zoning laws in some places,” Hartman wrote in one report to the Department of Public Welfare that “the record as a whole is not what it should be … zone changes under the guise of variances by boards of appeal, spot zoning by city governments and town meetings, and failure to enforce the law against violators, are all too common.”

Over the next few decades, that was often—but not always—the case in Great Barrington: Many residential properties were spot-zoned for business purposes. Among the most notable was the years-long, ultimately successful battle waged by heating-oil distributor Charles W. Agar to bury two 10,000-gallon fuel-oil tanks on his Hurlburt Road property. After the Planning Board repeatedly rejected his requests, he took the matter to a 1939 special-town meeting which granted approval and rezoned the parcel for commercial use.

Perhaps the Planning Board knew best: That property—which, unlike the airport, does not sit over the town’s municipal drinking-water aquifer and is just outside a groundwater-protection zone—would eventually have more than 100,000 gallons of fuel stored in single-walled underground steel tanks. And the business there would be cited repeatedly by state regulators for failing to meet tank-testing and other requirements, just as the airport was for nearly two decades. There was at least one fuel-oil spill at the Agar property and likely others that went unreported, threatening private drinking-water wells nearby, according to records on file with the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP).

A new ZBA and decades of variances

By 1936, Hartman was deeply worried about enforcement of the four-year-old bylaw. In a letter to one resident, he wrote that it was “time for the people of Great Barrington who are interested in the future success and desirability of the town as a place in which to live, to definitely organize themselves for the purpose of upholding the zoning law.”

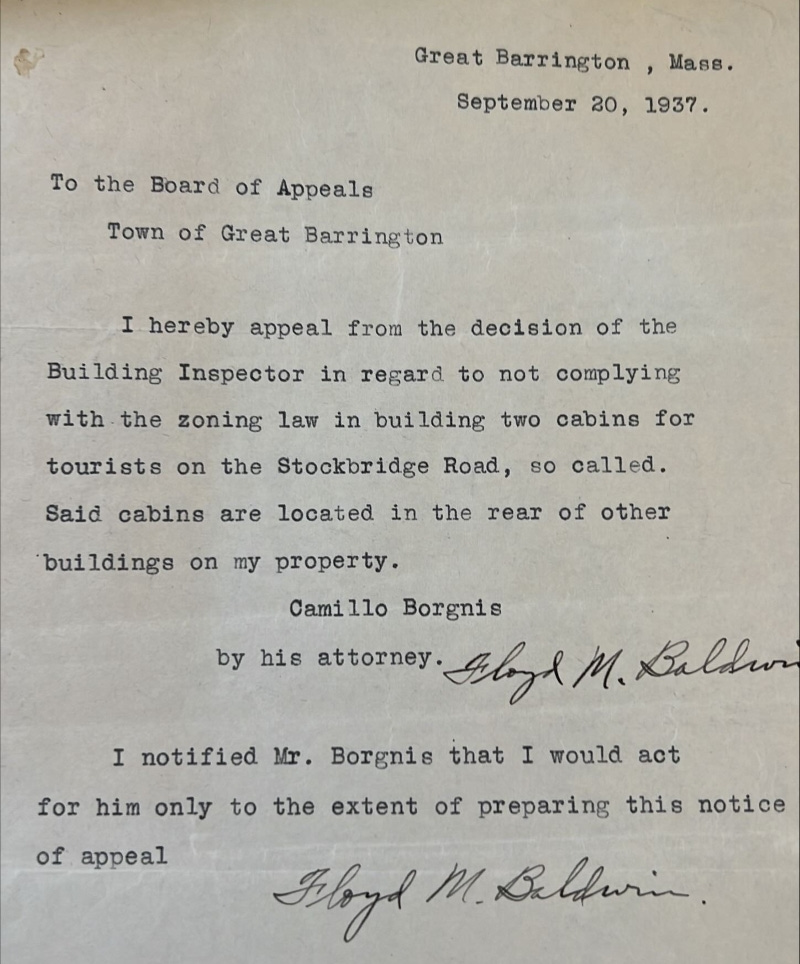

The following year, grumbling about restrictions on business in residential areas reached a fever pitch. It led to a petition drive, community meetings, and calls for the town to substantially revise the bylaw or even abolish its four-year experiment with zoning altogether. Instead, the town created a new, separate appeals board, the ZBA, to independently review decisions of the building inspector and hoped that would suffice.

Matters immediately considered by the new ZBA included granting approval to some tourist cabins—today we might call them “short-term rentals”—built illegally; allowing an automobile paint shop to continue operating in a residential district; and approving conversion of several homes from one- to two-family dwellings to add much-needed housing.

That the new ZBA was born in a different era is clear from its third-ever meeting, held in late 1937. That is when Camillo Borgnis, a nascent hotelier who immigrated to the Berkshires from Italy in 1913, appealed a zoning violation related to those tourist cabins built on his Stockbridge Road property. His appeal was filed by a local attorney, Floyd M. Baldwin—who, oddly enough, happened to be chairman of the ZBA. “I notified Mr. Borgnis that I would act for him only to the extent of preparing this notice of appeal,” Baldwin added helpfully at the bottom of a letter sent to his fellow board members. The ZBA voted unanimously to let the cabins remain.

The 1960 zoning changes

By the 1950s, as industrial development grew in nearby Berkshires towns that didn’t have strict zoning bylaws, frustration with Great Barrington’s limits intensified. The mood capped years of complaints and a belief that more business would help lower the tax rate. At the same time, a new zoning survey of the town and recommendations for bylaw changes were prepared by a New York City planner. But public hearings in 1958 weren’t fruitful; the proposals were met with opposition and criticism that they didn’t go far enough.

Much of the attack was led by Earl S. Jones, a local chicken farmer, lumber dealer, and owner of Joneses Antiques (where Guido’s Marketplace is today). He was also the controversial president of the Great Barrington Taxpayer’s Association, formed in the mid-1950s initially to oppose spending town money on a new school. Reported to have 500 members—who were generally not among the town’s political or business elite—the organization took on zoning, town spending, economic development, and assorted decisions of elected officials. One newspaper profile of Jones said he had offended just about every elected official in town with his brusque, outspoken manner and his constant commentary at nearly every board meeting. (In November 1956, Jones told the selectmen—whose public meetings he always attended—that he would be absent the following week because of the opening of deer-hunting season. According to the Eagle, his announcement was met with “peals of merriment.”)

After another zoning survey and accompanying bylaw changes were drafted in 1959, and meetings held with Jones and others, sweeping pro-business bylaw changes were approved in July 1960. The vote itself wasn’t a surprise: Accounts of an informational meeting held a few weeks earlier at Searles High School reported “a burst of applause” when a resident, Joseph Hazzard, spoke out in favor of substantial, pro-development changes. “Business brings taxes down. Let’s get some life and zone for business,” he said. Hazzard also suggested to the 60-odd attendees that the town throw out zoning altogether. “We don’t need it,” he said.

A Courier headline, “Voters’ Act Favors Business Growth,” spoke to changes that, it said, cleared the way “for business to expand in many areas.” A news story in the Eagle said the updated bylaw would “open this town for orderly industrial expansion” and that it was approved “without a word of dissent.” Selectman Cecil E. Brooks called it “a giant step into the future” for Great Barrington.

Large areas of town were rezoned, capping nearly three decades of variances and spot zoning. “The townspeople were in a mood to allow for expansion of business and industry,” the Courier reported, highlighting the rezoning of Route 7 from the Sheffield line to the Stockbridge border at the northern edge of town. Voters also approved all but one of the additional articles that rezoned specific residential properties for business or industrial use.

The surprising addition of Section 7.2

Perhaps surprisingly, then, the 1960 bylaw revisions added new language that put substantially tighter restrictions on one well-known business operating in a residential zone: the preexisting nonconforming airport. And on any future airport that might be built in Great Barrington.

The updated bylaw allowed an aviation field only in what was then the R2 residential zone, and only if “it is so located that it is not likely to become objectionable to adjoining and nearby property because of noise, traffic, or other objectionable conditions.” With the phrase “not likely to become,” the provision suggested an understanding that aviation was an expanding industry; the new language may also have been inspired by the experience of those living near Koladza’s ever-busier enterprise.

Richard Dohoney, an attorney who represented longtime Seekonk Cross Road residents Marc Fasteau and Anne Fredericks during 2017’s Selectboard hearings on a special permit and proposal to build new hangars, labeled this provision—favorably, given his clients’ interest in limiting growth—“by far the most restrictive zoning ordinance I’ve ever read in my entire life.” Dohoney argued that the reference to “adjoining and nearby” property showed town voters’ understanding that airport operations impact more than just legal abutters. (Fasteau and Fredericks, along with Seekonk Cross Road resident Holly Hamer, are plaintiffs in the zoning-enforcement case. Seventeen others also signed on to the legal filing.)

While news coverage in 1960 didn’t mention the genesis of the new airfield restriction, the Planning Board had spent months working through bylaw changes and engaging with the community—including meetings with Jones’ generally pro-development Taxpayer’s Association—as it pressed ahead. A May 16, 1960, letter to the Eagle from Karl Peiffer, chair of the board, said that his board members “contacted property owners and others directly involved in these proposed changes,” though he didn’t identify which property owners were consulted about which changes.

But the new provision immediately made it significantly harder for the existing airport to overcome that restrictive status if it sought, at some point, to come into compliance with zoning. The size of that hurdle was not lost on the airport’s current attorneys, whose recent special-permit application argued in several pages of legal analysis and case-law citations that the 1960 zoning language is inapplicable and unenforceable. They advised the Selectboard to ignore it entirely, even though the airport sought a special permit under that very section. (In a recent court filing, the airport’s attorneys challenged not only section 7.2 but also Great Barringtons’s entire zoning bylaw as it applies to the airport. The town responded with its own filing defending the bylaw, including 7.2, as valid, legal, and enforceable.)

Local zoning, aviation rules, and state regulation

Abrahams, the sole vote against the special permit last month, argued that the board couldn’t just ignore inconvenient language in a bylaw approved by town meeting. He also suggested the board’s conditions that sought to constrain the airport’s operations—an attempt to address the requirements of 7.2—are insufficient and unenforceable for both legal and logistical reasons. If true, it’s likely that airport-related litigation, including the resolution of the pending Land Court case, will focus on section 7.2.

Whether that section should be considered or ignored first became an issue in 2017. As part of an unrelated zoning-bylaw matter, Jeffrey DeCarlo, the administrator of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation’s (MassDOT) Aeronautics Division, wrote to the town about the language of 7.2 and his agency’s broad authority to approve all local rules, including bylaw provisions, related to aviation. He said that 7.2’s conditions for an aviation field were “very vague” and problematic because it meant, in the agency’s view, a “de facto prohibition of aviation.” He suggested the town consider softening the restriction.

But because the town’s 1960 approval of 7.2 predates the legislature’s 1985 grant of authority to Aeronautics to approve aviation-related local rules, it’s unclear whether DeCarlo’s suggestion carries legal weight. MassDOT spokesperson Kristen Pennucci declined to comment on whether the agency believes that 1985 authority applies retroactively to a bylaw provision approved earlier.

Town Counsel David Doneski wrote a 2020 memo that called DeCarlo’s comments “instructive” and proposed a tweak to the bylaw language. But this year he also advised the board that it should still consider 7.2’s language as it evaluated the airport’s application. The Selectboard’s findings repeat DeCarlo’s argument and state that a “de facto prohibition of aviation”—if that’s what exists under the current bylaw language—“would violate state and federal law.” It’s unclear whether that’s an accurate statement; it seems likely to be addressed in Land Court.

Perhaps ironically, that Aeronautics Division authority could lead to the rapid undoing of the airport’s new special permit. That is because the permit states that if any condition “is found invalid or otherwise unenforceable in any judicial review or by a governmental authority having jurisdiction, the Special Permit shall automatically become null and void.”

The special permit includes specific aviation-related conditions, among them a ban on flight-school operations on July 4 and Labor Day and establishing hours during which “continuous takeoffs and landings” are permitted. That activity—not defined in the permit but generally understood to mean circling the local flight pattern for repeat takeoffs and landings—is performed by flight-school students and by other pilots who, under the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) “recency” requirements, need at least three takeoffs and landings every 90 days to continue to carry passengers.

Under state law, those provisions can’t take effect until they are submitted to Aeronautics—regardless of whether the airport agrees to abide by them in any case, as it said it will. Town Planner Chris Rembold couldn’t provide any information last week on whether the special permit’s conditions have been submitted for approval, or if Aeronautics was consulted during drafting of the conditions.

It puts Aeronautics, an agency required by statute to champion and protect aviation, in a complicated position: If it approves even those very modest limits, it may open the door to restrictions on flight schools and other airport operations elsewhere in the Commonwealth. But if it disapproves the provisions, the special permit is invalid, and the airport returns to its preexisting nonconforming status. In that case, it would again need Selectboard or ZBA approvals to operate at its current level of activity, pending what unfolds in Land Court in the coming weeks.

When I asked MassDOT’s Pennucci whether Aeronautics would disapprove regulations of the days and times of operation of flight school aircraft as an unacceptable limit on aviation, she told me the agency “declines to comment on the specifics of your inquiry.” She said that more generally, the FAA regulates flight schools—but that’s typically in areas of curriculum, training-aircraft inspections, and pilot and instructor certifications.

Still, Pennucci confirmed the agency’s authority: “MassDOT Aeronautics has the statutory authority to review any local rule, regulation, ordinance or by-law relative to the use and operation of aircraft, and such rules and regulations, ordinances or by-laws are ineffective until and unless approved by the MassDOT Aeronautics Division,” she wrote in an email last month.

Did zoning prevent the airport’s sale in 1964?

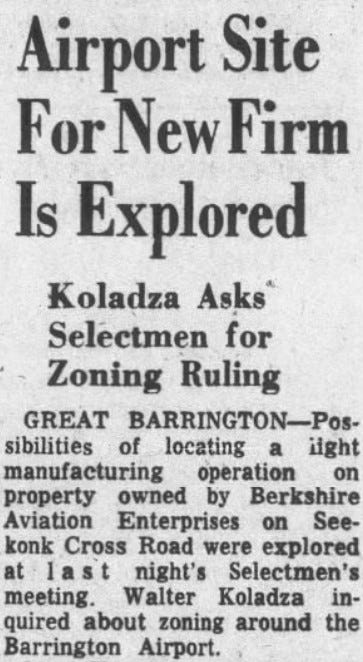

Just as in 1950, one day in April 1964, Koladza appeared before the selectmen with startling news and an urgent request. The Eagle reported on his appearance under the headline, “Airport Site for New Firm is Explored; Koladza Asks Selectmen for Zoning Ruling.”

Koladza, once again approaching the most influential town officials even though zoning was not their responsibility, said that a Boston-area manufacturer was interested in leasing or buying a significant portion of the airport. It planned to construct a 100-by-500-foot building where 70 employees would work, “with room for a second building.” Another area north of the runway would be blacktopped to provide parking for 150 cars. Koladza said the company could eventually double the number of employees, teasing the opportunity for significant employment opportunities in a small town.

But he wouldn’t identify the company, industry, or product to be manufactured. He would only reveal that it was “a well-established firm” in a business unrelated to aviation—and that it had two airplanes. Operations “would be conducted entirely indoors and quietly,” he said. As with his earlier racetrack proposal, Koladza inquired about zoning. “I want to know if the zoning in the airport area would allow a light manufacturing plant to operate,” he told the board.

Koladza surely already knew the answer. But he also knew two key facts. First, a Selectboard member, Herman G. Morelli, was a founder, shareholder, and vice president of the Barrington Industrial Corp. (BIC), an enterprise formed in 1956—with former airport owner Robert K. Wheeler as president—to attract and invest in industrial businesses in Great Barrington. And second, BIC had frequently led efforts to rezone properties from residential to industrial use to meet the requirements of firms connected to BIC.

Indeed, Morelli immediately said that he would talk to BIC about the project and recommended Koladza talk to his neighbors. Koladza agreed and told the board he didn’t want to “start a zoning war or antagonize my neighbors. I’m going to have to live beside the plant and look at it too,” he said. At the time, Koladza and his wife still lived on the airport property and would not move to a home on Seekonk Road until 1967.

Koladza acknowledged that his neighbors “had been more than considerate of the noise from the airplanes in the past.” But he also pointed to the economic-development possibilities: Most airports have businesses co-located on their properties, he said, and there was “the possibility that other small industries might build on the land not now being utilized” by the airport.

Koladza said the manufacturing plant would not only be quieter than airplanes using the airport, but also—using what again appeared to be the standard metric for measuring sound levels in Great Barrington—“quieter than the trucks which use Route 71.” As he left the meeting, Koladza threw in a little extra charm: He told the board that a photograph of the town displayed in town hall was “outdated” and offered to donate one featuring a view from the air.

The Eagle soon reported that prospects for the manufacturing plant were “good at this early stage, with town and BIC officials just starting the multitude of steps that precede the arrival of a new business to any area.”

Koladza appeared again the following week. He said he met with BIC and Morelli and enlisted their help in “determining public opinion of the proposal,” according to news reports. He also told the board he was unaware of any opposition to his plan and pressed them for rapid action. “I want to know, this week, what steps can be taken” on the zoning question, Koladza said.

The board was still waiting for an opinion from town counsel William Murtaugh. “I will call him right away,” James J. McDermott, another member of the board, assured Koladza. In the meantime, the selectmen said the ZBA could issue a variance, as a business was already operating at the property. Or, as recommended in 1950 for his racetrack, Koladza could ask the Planning Board to arrange a special town meeting and a vote on a permanent zoning change.

But by the following week, airport neighbors had organized their near unanimous opposition—a far cry from Koladza’s earlier claim. Clarence A. “Nick” Parrish, the Egremont Plain Road aviator who had also opposed a racetrack in 1950, said he polled airport neighbors and all but three opposed Koladza’s plan. Many were also upset the type of business was still a secret, leaving them unable to consider the level of activity and noise. But those details likely didn’t matter: Parrish said he would “oppose a pillow factory” at the airport (though it’s unclear how much noise a pillow factory makes).

Another complaint from neighbors was that none had heard directly from Koladza. They told the board they opposed any industry at the airport for a host of reasons. That included environmental concerns, with one abutter fearful that sewage and wastewater from the plant would be dumped into the Green River just upstream from the town water supply’s pumping station. One neighbor said she opposed spot zoning in a residential neighborhood. And another told the board that, while industry was needed in town, it should be in areas zoned for that purpose.

And that was it. Koladza withdrew his proposal, citing his neighbor’s opposition. “Because my neighbors are up in arms and because I would prefer not to sell the airport, I am withdrawing the airport from consideration for industrial development” he said, suggesting that sale of the entire property to the unknown firm may have been his plan. “I’m disappointed that my neighbors thought I would do something to despoil the area,” he added.

Koladza plows ahead

That possibility of an outright sale was not insignificant. At various times over the next two decades, state officials expressed interest in transforming the airport into a town-owned municipal airport. Primarily, they said, municipal ownership would prevent it from being sold for just the kind of non-aviation development Koladza sought in 1964. But it would mean a vastly different airport, eventually surrounded by security fencing and managed by the town—which would have to pay for its operations with a combination of local, state, and federal funds.

Koladza always ridiculed the idea, pointing out that Great Barrington enjoyed the benefits of a local airport without any direct cost to taxpayers. He also repeatedly declined federal funding from the FAA, as that money—along with certain MassDOT grants—comes with a legal commitment to maintain the property as an airport for at least 20 years. That would rule out selling the airport for any other purpose. Which, as the 1964 light-industrial-plant proposal and possible sale made clear, was in the mix.

In early 1974, when a state report again recommended turning Koladza’s private field into a permanent, municipally owned airport, he reminded the town that he ran “one of the best small fields in the country” and that he would “hate to see it go public.” But even then, he didn’t rule out selling the airport “under the right financial conditions,” which could include a sale for use as something besides an airport. He told the Eagle the property was suitable for other kinds of development, noting “there is a gravel bed beneath the field.”

And that’s true: Gravel excavated from the airport’s property was used in its 1957 runway project. And if that qualifies as a “legally preexisting gravel extraction bed” as specifically described in the town’s groundwater-protection bylaw, the property—despite being atop the town-water-supply’s aquifer—could again be used for that purpose. (A legal battle would surely be waged over whether that use has been abandoned and therefore requires a special permit from the ZBA.)

With a sale off the table in 1964, and Koladza reminded of the challenge the airport’s zoning status presented for any future sale or development, he pressed ahead with expanding airport operations. The timing was good: His plans aligned with a new round of GI Bill education benefits that again paid for flight training for military veterans. Just as it had been until the mid-1950s, that would be a significant revenue stream for the airport over the next two decades.

News coverage continued to chronicle Koladza’s activities and favorably report on much of what he did. “Airport Receives New Plane,” was the headline of a 1965 article about a new, six-seat, twin-engine Piper Aztec put into active use in BAE’s charter service. (In 1987, it would be the plane that struck the top of a passing car on Seekonk Cross Road while landing.)

In March 1965, Koladza announced that “business pressure” had made the airport’s current facilities insufficient for the level of aircraft maintenance and flight training underway, and detailed plans for additions. His overall business was up by 30 percent the prior year, he told the Eagle.

Tom Bleezarde, a reporter who had long covered the airport, followed up with a column titled, “Business Is Looking Up,” detailing the airport’s continued growth. “No other business in Southern Berkshire has as graphic evidence of growth over two decades as that exhibited daily by Berkshire Aviation Enterprises,” he started out. He chronicled the airport’s history and the “true visionaries” at its helm since its founding and reported that the flight school had seen 40 percent growth over the prior year.

Continuing evolution of the zoning bylaw

The evolution of Great Barrington’s zoning bylaw continued through the 1960s and 70s—and since—with key town officials earning reputations for their interest in upholding its provisions, evolving them to meet new challenges, or both.

At the top of that list is the late John W.P. Mooney, a brilliant journalist, longtime town official, and well-known stickler for the rules. Like Edward T. Hartman before him—they are not related by blood but deeply connected by outlook—Mooney believed strongly in both the power of a well-crafted zoning bylaw and, too often, the accompanying weakness of town boards to enforce it consistently in the face of political and other pressures.

In 1972, as the town continued to struggle with conflicts created by growth and the arrival of well-heeled developers, he published an op-ed criticizing the 1960 bylaw and those who sought to subvert it. “It is perhaps one of the clumsiest bylaws ever devised,” he wrote in the Eagle, “requiring the wisdom of Solomon and the patience of Job to enforce, and only the shrewdness of a slick layer to subvert.” Having served on town boards as well as covered its members as a journalist—often quite critically—Mooney didn’t stop there. “Since slick lawyers are far more common at zoning hearings than Solomon and Job, the results are predictable,” he argued.

Channeling Hartman from two generations prior, he concluded his op-ed this way: “The commercial interests are battering at the door in force, and the present Board of Selectmen has shown itself only too susceptible to their pleas.” He called for a complete re-write of the zoning bylaw, and that’s precisely what the town’s Planning Board shortly undertook.

In June 1974, changes were approved that limited development in floodplains, and according to the Eagle’s summary, “updated use regulations and zoning to allow the town to direct land use better under increasing land development pressures, and to align the zoning bylaw with the objectives of the [new] master plan.” The 1974 changes also rezoned the area around the airport to the new R4 zone, the only one in GB requiring large, two-acre residential lots. It was labeled an “agricultural/institutional/watershed zone” and was also applied to the area between Monument Mountain and Beartown State Forest.

Mooney was smart, funny, and could also be notoriously prickly—perhaps most of all when he showed little patience for old-boys-club-type cutting of corners or outright rule-breaking. His outsider status began early: He first won election to the Selectboard in 1970 as an independent after being denied a Democratic Party nomination. He would spend decades serving in some capacity in town government until his death in 2008.

The Eagle’s endorsement of his successful 1988 re-election to the Selectboard conceded he was often “unbending” when it came to defending the zoning bylaw, came across as a “know-it-all,” and was “irascible” and “annoying.” But it heaped praise on Mooney’s early and important work on affordable housing, environmental protection, and longstanding concern about the risks of unchecked development. Indeed, the pro-Mooney editorial warned presciently that Great Barrington was in danger of “becoming prey to the kind of excessive development that both ruins its small-town charm and makes it too expensive for borners,” using local slang for lifelong residents.

Noise complaints on the other side of town

Any zoning bylaw has, as a fundamental premise, the protection of preexisting nonconforming properties and uses. That ensures that even as communities mold their future with zoning changes, property owners’ existing rights are protected, even if they are constrained from new or substantially expanded uses. The argument made over the last 18 months by airport neighbors has been that the town, over generations, failed to properly constrain the airport’s preexisting nonconforming use. They asked the town to do so, and the town refused, arguing that any growth in operations over time was permissible.

The Selectboard, ZBA, and Building Department unanimously took a different view of a strikingly similar matter that unfolded in parallel to the airport controversy since 2017. Though it more accurately can be said to have begun in 2011—and perhaps as early as 1996—that other matter was complaints about the noise, hours, and level of activity of another preexisting nonconforming business use: Gary J. O’Brien’s trucking and plowing business that operated from the top of Roger Road, in a residential neighborhood on the other side of town from the airport.

In that case, neighbors repeatedly approached town officials to complain bitterly—and sometimes angrily—about substantially increased activity, including large trucks and their noisy air brakes passing by their homes at all hours of the day and night. The neighborhood, which includes Blue Hill Road, had grown up around a location where trucking operations had been taking place since 1929—something that mirrors what airport advocates say has happened near the airport over that same period.

But the complaints of O’Brien’s neighbors about noise, vibration, and air pollution led to numerous violations issued by the building inspector; multiple ZBA proceedings; a lawsuit in Berkshire Superior Court; at least $80,000 in fines that went unpaid; meetings and conference calls among lawyers; a failed effort by the Selectboard to convince town voters to buy the property outright after zoning enforcement failed; and, ultimately, to Land Court litigation brought by O’Brien in which he won an injunction against the town.

One of the town’s cease-and-desist orders noted an “increase in intensity” of trucking operations that was “substantially more detrimental to the neighborhood”—key legal metrics also at issue in the airport case. (The language is a reference to the “Powers tests,” named for criteria established by a 1972 Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court decision, Powers v. Building Inspector of Barnstable.) It called on O’Brien to stop operating an additional, unauthorized landscaping business and curtail trucking activities beyond a level agreed upon in 1996 with a prior owner of the property.

Nearly every time it came before town officials, they unanimously supported the neighbors’ requests for zoning enforcement. And some of those officials were visibly frustrated by the failure of the town to enforce its own decisions—including then-Selectboard Vice Chair Bannon. “The process is disappointing to say the least. The neighbors deserve better,” he said at a December 2018 Selectboard meeting that included heated comments from residents. “The cease-and-desist order isn’t worth the paper it was printed on if we don’t enforce it.” He told neighbors to call the police every time a large truck passed by their homes to create an evidentiary record.

The two matters are not identical, but both feature preexisting nonconforming uses that increased substantially and led to years of complaints. In both cases, the town was asked to evaluate the impact on the respective neighborhoods. When I asked Bannon this week about the similarities between the airport controversy and the years-long battle over noise and disturbance at O’Brien’s property, he said he didn’t think it was useful to compare unrelated enforcement matters. But he said he always listens to neighbors. “It’s not a matter of listening,” he said. “It’s a matter of deciding [on] some sort of a solution to a problem.”

The town’s legal expenses

Ultimately, a court-brokered settlement addressed at least some of the O’Brien neighbors’ concerns, particularly around truck traffic in the very early morning; other operations had already been relocated to O’Brien’s facility in Lee. But not before the town spent $55,379 in legal fees over nearly five years, from 2017 to 2021, according to invoices obtained by the Argus in a public records request.

The potential cost to defend the town’s position on the airport was among the arguments made this year by those advocating for a special permit. They claimed the town would spend $100,000 in legal fees defending the ZBA’s April 2022 decision upholding the building inspector’s ruling. One post on the popular Great Barrington Community Board on Facebook said the appeal would “cost over $30,000 per week, paid for by GB taxpayers.” It was one of many fact-challenged social-media posts in recent years that seemed designed to stoke anger at airport neighbors.

In fact, through November 30, 2022, not long before the case was put on hold during the special-permit hearings, the town had spent a total of $6,904 in legal fees on the neighbors’ Land Court appeal, which was at that point nearing a decision. During the six months in advance of the ZBA’s airport hearing, the town had spent $5,070 related to the zoning-enforcement request, for a total of $12,000 over a year, according to the documents obtained via public records requests.

That compares with $5,032 spent by the town on legal fees related to the airport’s unsuccessful 2020 special-permit-and-hangars application; $2,467.50 on issues related to the airport’s 2018 fuel-tank replacement and use of refueling trucks in violation of a groundwater-protection bylaw; and $1,645 on the airport’s 2017 special-permit application, which was withdrawn after five months of hearings. From 2010 to 2013, the town also spent an estimated $14,000 to rebut claims by airport neighbors Claudia Shapiro and Danny Bell that events at the airport, like Rotary’s BikeNFly fundraisers, are not permitted under the zoning bylaw.

The ZBA’s support of the airport

As for the ZBA’s differing positions on the O’Brien and airport matters, it’s clear the ZBA has long been a friendly venue for the airport, though some of its members told me that all appeals are evaluated individually.

Prior to the April 2022 hearing on the airport zoning-enforcement request, which had been denied in November 2021 by the building inspector, longtime chair Ron Majdalany sent an email to other board members as they settled on a date for the hearing. “Tuesdays are all open for me,” he wrote, adding, “I don’t like the board’s increasing use as a tool for harassment, however.” (The email was obtained by the Argus in a public records request.)

That sentiment was repeated by board member Steve McAlister, a local architect, who during the hearing also called the neighbors’ request “harassment” and said it was “an absurdity”—particularly the nearly century-long lookback to when the airport became nonconforming in 1932. “I’m ticked off because I feel this is a waste of this board’s time,” he said. (McAlister declined an interview request, citing the Land Court case.)

When I spoke to Majdalany, a retired veterinarian, last December, he also said he couldn’t discuss the airport because of the ongoing litigation. A member of the board since the late 1980s—and currently the longest serving elected official in Great Barrington—he did say that appeals of the board’s decisions to Land Court are “infrequent.”

Having seen countless issues come before the ZBA, I asked him what he’s taken away from his review of so many zoning matters over nearly four decades. “What I’ve learned is to just listen carefully to all parties and try to evaluate how their needs fit in with the zoning bylaws, which are pretty clearly stated,” he said. “There’s not a lot of ambiguity, but we often have to make judgment calls. The important thing is to listen to all sides and then make an appropriate decision.”

Michael Wise, a ZBA member and retired government lawyer, led the skeptical questioning of the neighbors’ attorney during that 2022 hearing. He told me in December that the ZBA must make “inferences and judgments about the facts where direct evidence is incomplete.” But he suggested there was ample evidence of the airport’s early operations, and—though it was not mentioned in the ZBA’s findings or unanimous decision—that the evolution of aviation should be considered when evaluating permissible growth. “It almost goes without saying,” he said.

The neighbors’ attorney took a different view, arguing that the airport “drastically exceed[s] in scale and scope its operations at the time it first became preexisting nonconforming,” which was in 1932, when little was happening at the airport. The ZBA conceded as much, noting in its decision, “Roughly current levels of intensity were probably reached not long after operations began, when the field was used for training pilots during WWII.”

As examined in depth in part two of this series, the airport was indeed quite busy during WWII. But that was more than a decade after the airport became preexisting nonconforming, and that’s at the heart of the legal and zoning questions. Regarding that 90-year lookback, Wise said he reviewed cases that involved expansions of preexisting nonconforming uses and found none that looked back more than 20 years. “I couldn’t find a single one that, in applying the tests, says you must go back 90 years,” he said. He also argued that in the O’Brien matter, complaints began in the mid-1990s, while airport neighbors didn’t seek zoning enforcement until what Wise said was “relatively recently.”

Wise’s and the ZBA’s opinion that going back 90 years is “absurd,” as McAlister put it, was on track to be examined closely by Judge Piper in Land Court. But with a special permit now in the mix, that potentially novel legal question may not be specifically addressed in the pending decision.

A question of enforcement, yet again

What’s notable about testimony provided to the Selectboard during the recent airport hearings—particularly in written comments sent in advance of February’s first hearing—is that almost to a person, neighbors who have lived near the airport for decades don’t mind having a small airport nearby. Some enjoy its “charm” and the “colorful small planes swooping through the sky.” Their concern, expressed since at least 2017, is that operations have grown considerably with no end in sight, raising “safety, environmental, and quality-of-life” issues, as one wrote.

That’s why the Selectboard’s failure to follow its town counsel’s advice, and thoroughly benchmark the airport’s current level of activities, raises reasonable questions about the ultimate effectiveness of the recently granted special permit and the town’s enforcement plan. The first of the permit’s conditions states unequivocally that it is meant to only allow airport operations as they “currently exist.” While that level of activity is notably higher than even a year ago, how will the town monitor or, if necessary, enforce that basic premise?

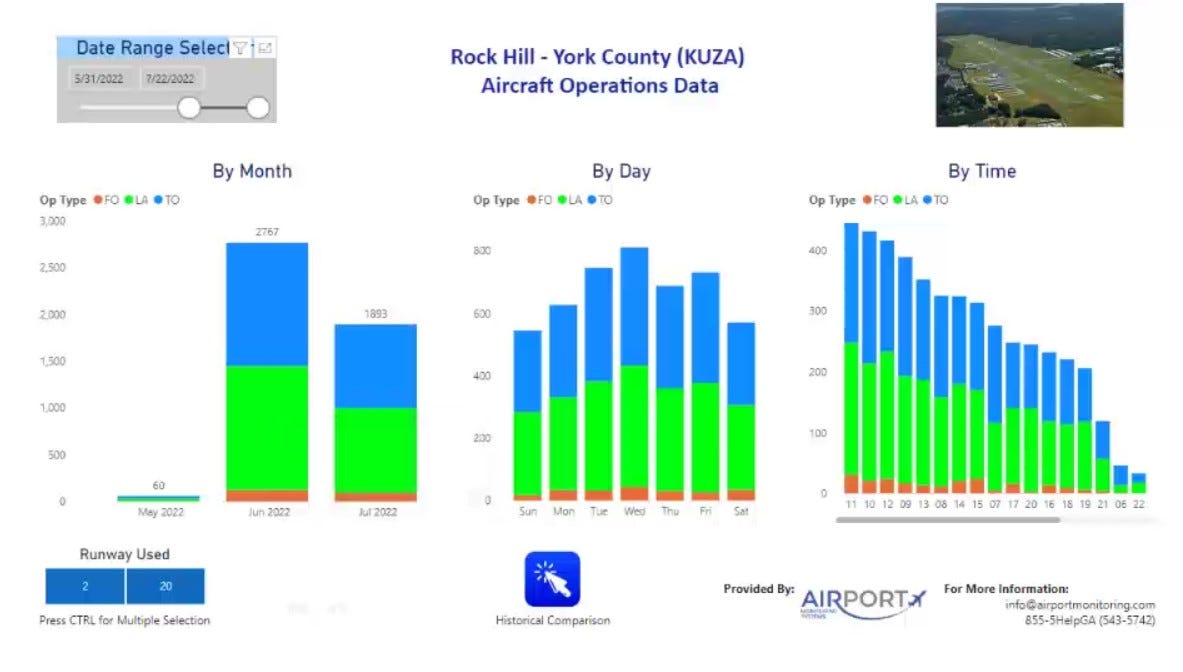

The board didn’t require, for example, that the airport to install operations-counting technology like the feature-rich Virtower ($500 per month), Airport Monitoring Systems ($150 per month), or fully utilize the G.A.R.D. operations-counting system already in place, but currently unused, at the airport. Hundreds of other airports use these technologies because they provide detailed, useful information that replaces speculation and community-roiling accusations about noise, low flights, and pilots flying out of established flight patterns. Such a tool—which requires only installation of a small device at the airport that is connected to power and the Internet—would also give the town the ability to evaluate, and, if necessary, enforce the permit’s key conditions.

Because of the level of distrust that’s built up over the years between the airport and its neighbors, it’s notable that no such requirement was mandated. The board also failed to require that the airport’s flight-school planes, which make up a sizeable portion of locally intense air traffic, remain visible to publicly available tracking services like FlightAware. Or, given neighbors’ concerns about airborne lead, mandate that BAE’s planes use unleaded fuel it already sells on-site. Recent studies have shown elevated blood-lead levels in children living very close to general-aviation airports in California and Michigan—even when soil tests at those airports, like those now required every five years at Great Barrington, show normal lead levels.

A limit on public comment

These and other issues might have been more fully discussed—and useful ideas explored—in public comment during the hearings. But a fundamental difference from previous airport-related hearings was that, in 2017 and 2020, neighbors and their attorneys were allowed to comment deep into the process, as well as those supporting the airport’s applications.

But this time, no public comment was permitted after the first hearing on February 27, other than via email. Even as information was presented by the airport’s attorney, Dennis Egan, and conditions crafted over several meetings, no other voices—pro, con, or simply to correct the record or add helpful information—were allowed in real time. It was only a discussion among board members, airport representatives, and town counsel.

When I asked Bannon about his decision to run this year’s process differently than in 2020, when he was also board chair, he said he felt the board received all the information it needed. “What I want to do is have a really good discussion with the applicant after we know the concerns from the public, and then craft the conditions around that,” he told me this week.

Bannon said no board members complained to him about the process, and that he would have listened if they had. After hearing public comment on that first day, “I thought the way to get the best result was just to have a conversation with the applicant,” he said. There were additional public meetings on March 13, April 3, and April 10.

For his part, Abrahams praised Bannon for his board stewardship and longstanding commitment to fairness. He said he also generally deferred to him, as chairman, when it came to hearing rules. But in this case, Abrahams said it was a mistake to limit public comment—though he concedes he didn’t raise his concern with Bannon. “I did not think the process was fair,” Abrahams told me last week. That was particularly true, he said, as the board crafted conditions. “At no point did we look at anyone else and say, ‘What do you think?’ I just think that’s wrong. I disagree with that,” he said.

On enforcing the level of airport activity, Abrahams said, in retrospect, it might have been useful to get an expert to provide the board with information on tools available to track flight operations. “On the other hand, it’s the job of the applicant to come in and show us, ‘Here’s why you don’t need to worry about any of this,’” he said.

Bannon said none of the neighbors suggested the use of technology to count flight operations and defended the decision not to hire an independent aviation consultant to help inform the board, saying he didn’t want “to get bogged down for months.” He said that can happen “when you have multiple experts from different areas all with different ideas.”

Given Bannon’s prior experience with extended airport special-permit processes, it’s understandable that he sought to avoid repeat arguments and unneeded delay. Still, expecting airport neighbors to tell the Selectboard what’s required to enforce the conditions the board itself just drafted seems an unusual request. But on the broader question of enforcement, Bannon has faith it will work out. “I think the building inspector will have a lot to do with it. I think neighbors who are concerned with growth will have something to do with it. And I think the airport as an ethical business will have something to do with it,” he said.

Still, he conceded the town is understaffed and lacking resources for the job. “I’m not sure the tools are in place [to monitor flight operations], nor do we have the staff for a lot of what we do. We do the best we can,” he told me. “I think it will be fine. I’m very comfortable with it,” he said.

Davis’s unanswered questions

During the hearings, Vice Chair Davis repeatedly pressed the airport’s attorney on the need to establish that accurate benchmark of airport activities, as directed by the town’s counsel. At a March 13 hearing, she called the airport’s application “insufficient” without that information. “If this is to move ahead, we have to specify what exists now … just to have on record what we’re agreeing to,” she said.

In an interview last week, Davis described that early part of the process. “It’s hard to make a decision without really having something to start with,” she told me. “I was trying to really bring it back to where are we right now, and how can we make a determination on the future.”

But ultimately, the board never got that information. “That doesn’t mean that my vote would have changed,” she said. “We don’t have a crystal ball, and we don’t really know what’s going to happen. From my perspective, I felt like I made the best decision for the community.”

When I asked Davis about the difference between her opposition to 2020’s special permit and support of this one, she said it was “unfair” to draw that comparison. “For me, it was a new [application] and new information was presented. It was a clean slate,” she said.

A few minutes before the board voted to approve the permit on April 10, Davis again raised concerns about enforcement of conditions the board had just finished drafting. “We have one person enforcing this … I want to make sure there’s a way to enforce this,” she said, referring to the building inspector, Ed May. In response, Town Manager Mark Pruhenski said only that the town hoped to fill a long-vacant position for an assistant building inspector, but there was no further discussion.

Davis could not offer any specifics about what will happen next. “In terms of enforcement, I’m not really sure how that would look,” she said last week. “I would just hope that someone’s accountable and the proper procedures are followed.”

In that context, whether officials will be proactive or wait for complaints is a crucial unknown; the town has many authorities in its zoning bylaw, ordinances, and in special-permit conditions that if often does not use. As it relates to the airport, among the most notable is language in the 2006 groundwater-protection bylaw that allowed the airport’s 24,000 gallons of underground fuel storage—located above the aquifer that feeds the town’s primary municipal water supply—to remain.

It also specifically empowers the Building Department, Board of Health, and Fire Department to closely monitor the airport’s compliance with state and federal laws that regulate underground fuel-storage tanks, including with unannounced, on-site inspections of relevant records. But as reported in part four of this series, over 17 years, the town has never exercised that authority, even as the airport was repeatedly cited by state regulators for years of failure to properly monitor and test its aging single-walled steel tanks. (In 2018, one 20,000-gallon tank was upgraded to a fiberglass, double-walled, alarmed unit; a 4,000-gallon tank was removed and not replaced. No evidence of leaks was found during a related environmental investigation.)

Last week I emailed both May and Pruhenski to ask how the town will monitor various special-permit conditions and ensure compliance. May didn’t respond and Pruhenski told me that he, May, and other town officials can’t comment on the airport while the Land Court case is ongoing.

An unknown future

In the end, those attracted to aviation say they enjoy the freedom it provides. Indeed, when I asked Jim Jacobs, a part owner of the airport, what he liked most about aviation, that’s what he said. He has several airplanes based at the airport along with a Robinson R44 helicopter that he told me he likes to take up most mornings during the spring and summer.

As an example of what aviation means to him, Jacobs said that he can fly all the way across the country, stopping to refuel at little airports along the way, “and never have to talk to a single person.” That’s a particular kind of freedom, for sure, and reflects a certain worldview. And perhaps it’s emblematic of aviators who, moved by the powerful experience of controlling one’s destiny in the air, are wired to chafe against rules and constraints imposed by others.

Zoning, a democratically agreed-upon set of rules in a community, is most certainly one of those constraints. It would be interesting to know what Edward T. Hartman, who brought zoning to Great Barrington, would make of today’s airport controversy. In the 1930s, Hartman was likely to blame town officials for allowing his dreaded “encroachments” into residential neighborhoods and forcing residents to struggle for remedies. “There are legalized, so-called, violations, where boards of appeal permit unlawful intrusions,” he wrote in 1936. “To solve these problems, citizens have to go to court and overturn the work of the boards, as has been done repeatedly in Massachusetts and elsewhere. The expense of correcting these errors should not have to fall on private citizens.”

Still, Hartman was committed to the idea that, properly implemented and enforced, zoning can help a community strike a balance that lasts. But balance is the key, particularly when navigating preexisting development and uses. “The primary purposes of zoning are to adapt certain things yet to be done to certain related things already done,” he said about that challenge, “so that the two may complement each other and function together. Neither function should be allowed to destroy the other.”

It may be that in rushing to “save the airport,” the Great Barrington Selectboard has only kicked various cans down various roads with a difficult-to-enforce permit that doesn’t do enough. At minimum, it’s now up to the town’s single building inspector—with no aviation expertise, few resources, and lacking informational tools that could assist him—to, principally, ensure the airport’s operations remain generally at a level that was never specified.

In many ways, that was the status quo ante under the airport’s preexisting nonconforming status. How this outcome represents a balanced, comprehensive, and permanent solution—and not an invitation to increased activity, continuing complaints, unaddressed environmental risks, and perhaps future litigation—is not easily explained. Given the unusual contentiousness that continues to swirl in the community, that’s not good for Great Barrington. It’s also, arguably, a disservice to the airport and those who cherish it.

∎ ∎ ∎