When Berkshire Health Systems initially disclosed to state and federal regulators this summer that a “rogue employee” at Great Barrington’s Fairview Hospital had improperly accessed patient medical records, it suggested the breach affected between six hundred fifty and one thousand patients—and possibly more, according to filings made by its privacy officer.

But documents obtained this week by The Argus also reveal that B.H.S. said it would be an “undue burden” to look back more than three years to determine which patients’ records were accessed. At the same time, B.H.S. acknowledged the breach may stretch back to 2014—raising questions about its data-privacy auditing, how many patients were affected, and why it chose such a narrow review.

The various filings may also reflect a familiar pattern in the way large organizations respond to data breaches: initial minimization, narrow legal framing, and then later revisions about the type and scope of data-privacy violations.

The filings

The documents obtained by The Argus include a July 30, 2025 letter to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services from Erin Mirante, a B.H.S. compliance and privacy officer. She wrote that on June 3, 2025, B.H.S. “received a report indicating that a Fairview Hospital employee in the Surgical Services Department may have accessed patient records within the B.H.S. electronic medical record system without a legitimate business purpose.”

In the letter, Mirante said “B.H.S. promptly initiated a thorough internal investigation,” which remains ongoing. The inquiry, she said, “suggests that the employee accessed multiple patient records without authorization over a long period potentially dating as far back as the date Fairview Hospital hired the employee in 2014.”

Sensitive information such as full names, dates of birth, account numbers, diagnosis codes, and visit notes was viewed. But B.H.S. said it found no evidence the data was “downloaded, printed, or otherwise acquired,” and said the now-former employee denied disclosing it.

The number of people already known to be affected varies across filings. Data submitted to H.H.S. and now posted to its public breach portal say one thousand individuals; a Connecticut filing obtained by The Argus put the total at 654, including sixteen state residents; and a July 30 letter to New Hampshire officials that did not detail a total number and said just one N.H. resident was affected. In each case, B.H.S. cautioned that more patients may be identified as the investigation continues.

Even a seemingly central fact—whether the employee worked in Fairview Hospital’s Surgical Services Department or another part of the sprawling B.H.S. system—has already shifted, despite what was described as a two-month-long “thorough internal investigation.” In an amended submission filed with H.H.S. on Wednesday and forwarded to Connecticut officials, though still dated July 30, B.H.S. changed its description of the employee from a Fairview staffer to “a B.H.S. employee in the Surgical Services Department.”

B.H.S. spokesperson Michael Leary declined to explain the reason for the change, reveal where the employee worked within B.H.S. between their hiring at Fairview in 2014 and their dismissal this summer, or answer any of more than a dozen detailed written questions from The Argus.

In a statement, Leary said that B.H.S. “prohibits unauthorized access to patients’ medical information by employees across the system” and said the health system has “taken appropriate actions, including optimization of privacy monitoring software, to ensure this type of incident does not occur again.”

In her letter to H.H.S., Mirante noted that B.H.S. will re-educate all staff on privacy and security requirements under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, commonly known as HIPAA. She also wrote, “Recently, not related to this incident, BHS deployed enhanced auditing and monitoring software to detect and flag unauthorized access to [personal health information].”

Whether the case has been referred for potential criminal investigation also remains unclear, though criminal charges for HIPAA violations are rare unless information is used maliciously or for personal gain.

Julia Sabourin, a spokesperson for Berkshire County District Attorney Timothy Shugrue, said she “can’t confirm or deny” any investigation and referred questions to the Pittsfield Police Department, which did not respond to an inquiry. Great Barrington Police Chief Paul Storti said his department did not receive a referral.

Limited review, “undue burden”

Even as it acknowledged that the repeated unauthorized access may date back to 2014, B.H.S. told regulators it will only review records as far back as October 1, 2022. That, Mirante suggested to H.H.S., represents “reasonable diligence” under HIPAA privacy and security rules, though she suggested B.H.S. could “reassess” its plan during its investigation.

But looking further back, she argued, would require searching “an archived system that functions very slowly and would exponentially increase the time and resources needed to conduct the review.” That would impose an “undue burden,” she wrote, because B.H.S. is “a small nonprofit health system in rural Berkshire County.”

That description may be difficult to square with the system’s actual scale: B.H.S. employs more than four thousand people, provides about ninety percent of health-care services in Berkshire County, has annual revenues approaching one billion dollars, and has operating margins among the highest of any Massachusetts hospital system, according to state data.

B.H.S. told federal officials that three employees in its compliance-and-privacy department will each spend twenty hours a week for six months—a total of fifteen hundred hours—on the investigation. Leary did not respond to questions about what data those employees will examine during that six-month review, or why patients whose information was improperly viewed between 2014 and 2022 may never be identified and notified.

Mirante also told H.H.S. that the improper access of patient data since 2014 should not be considered a single large-scale breach, but rather “a series of individual breaches” by the same unauthorized employee. That framing may be a legal strategy: a breach affecting five hundred or more people requires public notice within sixty days, while breaches under that threshold can be reported to H.H.S. once a year, delaying broader disclosure.

It’s unclear whether H.H.S.’s Office for Civil Rights, which enforces HIPAA data-privacy rules, will endorse that characterization, which may depend on legal interpretations of specific language in HIPAA regulations. If not, B.H.S. could face scrutiny not only for the breach but also for any delay in notifying the public.

“If a rogue employee accesses patient information and looks at it, that is a ‘use,’ not a ‘disclosure.’ Now, if the rogue employee sends that information to People Magazine, or puts it on social media so that other people can read it, or tells their partner or neighbor about it, then that is a ‘disclosure.’”

—Stacey Tovino, John B. Turner Chair in Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law

It’s also unclear if B.H.S. provided the required proactive, detailed notice to major media outlets that’s required within sixty days of a breach impacting more than five hundred residents of a single state, as required under HIPAA regulations.

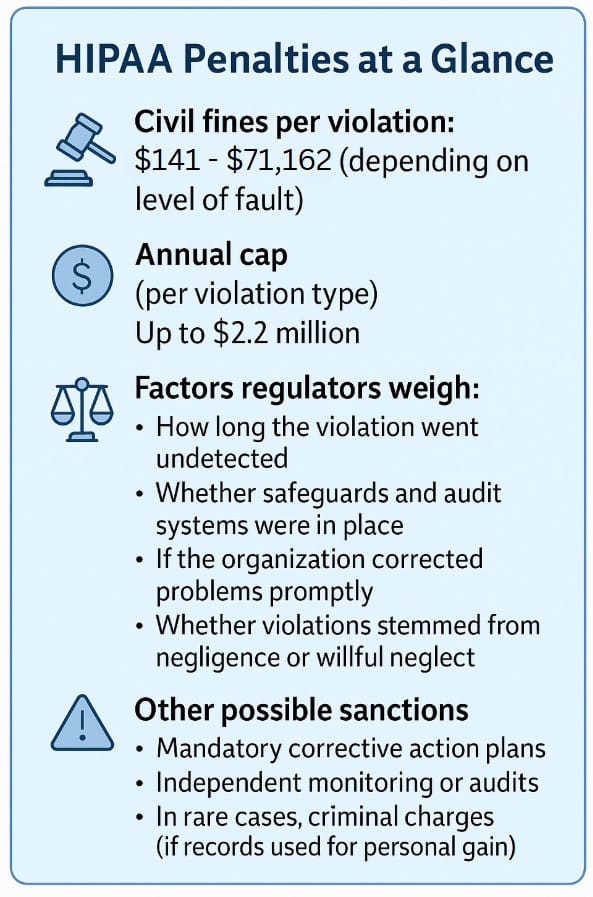

If federal regulators determine that B.H.S. failed to maintain adequate safeguards or audit controls, the organization could face significant HIPAA penalties. Civil fines can run from a few hundred dollars to more than seventy thousand dollars per violation, with annual caps that can exceed two million dollars, though H.H.S. has some discretion in determining the amounts.

Factors considered include whether violations stemmed from negligence or willful neglect, and whether corrective action was taken quickly. A decade of ongoing unauthorized access by an employee may test whether B.H.S.’s monitoring systems met HIPAA’s regulatory mandate to “regularly review records of information system activity, such as audit logs, access reports, and security incident tracking reports,” and raises the prospect of both financial penalties and mandated compliance oversight.

(Mirante declined to comment and referred questions to Leary. The H.H.S. press secretary, Emily Hilliard, said the department “does not comment on ongoing investigations.”)

Patient notification letters

While state laws differ on what must be reported and when, affected patients in several states began receiving notices around July 30, according to B.H.S.’s filings. It provided regulators with a template letter used for affected individuals that includes the date of discovery, the first date records were accessed, the number of times viewed, and up to five locations where improper access occurred.

It remains unclear what scope and timeframe B.H.S. used to provide patients with those data points. The letter assures patients that “B.H.S. takes privacy seriously, and we have systems in place to prevent inappropriate access to medical records.”

What can affected patients do?

While individuals can’t sue under HIPAA itself for a breach of privacy, they can file complaints with the Office of Civil Rights at H.H.S., ask state attorneys general to act, or bring claims under state laws related to confidentiality or invasion of privacy. Modifications to HIPAA under the 2009 HITECH Act expanded penalties for breaches of medical information and empowered state attorneys general to sue on behalf of patients.

Under HIPAA, patients have the right to request an “accounting of disclosures” of their protected health information over the prior six years. But this covers only disclosures made outside the covered entity, not internal access or use of records by employees, even when that access was improper or unauthorized.

Stacey Ann Tovino, the John B. Turner Chair in Law at the University of Oklahoma College of Law and an expert in HIPAA privacy rules, said that’s a key distinction. “If a rogue employee accesses patient information and looks at it, that is a ‘use,’ not a ‘disclosure,’” she wrote in an e-mail. But, she added, if the employee “sends that information to People Magazine, or puts it on social media so that other people can read it, or tells their partner or neighbor about it, then that is a ‘disclosure.’”

In a similar case this summer at the University of Miami Health System, an employee was fired after discovery of their improper viewing of medical records for nearly three thousand patients over two and a half years. As with the information released so far about the breach at B.H.S., the U.M.H.S. employee reportedly did not access Social Security numbers or financial information, but that hospital system is still offering complimentary credit monitoring and identity-theft-protection services to affected patients.

Some well-known cases of employee snooping include a 2011 settlement with UCLA Health System over years of employees improperly accessing the medical records of celebrities and other patients. In Massachusetts, in 2018, Gov. Maura Healey, who was then the state’s attorney general, fined a Belmont psychiatric hospital $75,000 for losing backup tapes containing patient medical information, and, in a more significant breach, settled with UMass Memorial Health Care for $230,000 after employees improperly accessed patient information and used it to open credit card and cellphone accounts.

Fairview fundraising and expansion

The claim that a full review of ten years of the former employee’s patient-access data would be an “undue burden” came as B.H.S. advanced plans for an estimated seventy million dollar renovation and expansion of Fairview Hospital that will expand its emergency room facilities, renovate patient rooms, add a magnetic-resonance-imaging unit, and upgrade surgical suites.

A Fitch Ratings report earlier this year said the project would be financed with $45 million in new debt, $15 million in internal cash, and $10 million in community fundraising. B.H.S. presented its architectural plans for the project at a public event on July 22.

Normally, such projects require approval under the state’s Determination of Need process, a detailed regulatory application and review designed to ensure hospital expansions are justified and in the public interest. Lawmakers recently tightened that law after the collapse of Steward Health Care raised alarms about risky hospital finances and prompted closer scrutiny of hospital projects statewide.

A Department of Health spokesperson told The Argus that B.H.S. has not yet filed an application to begin the DoN process for the Fairview project and said that once a complete application has been received, it kicks off a four-month regulatory review. Rep. Leigh Davis (D–Great Barrington) also filed a bill earlier this year that seeks to exempt Fairview’s renovation and expansion plans from the review process entirely.

State and federal rules

The breach-notification filings highlight the confusing and often-complicated patchwork of state and federal data-privacy laws. Under HIPAA, covered entities must notify H.H.S. and affected individuals when unsecured health information for five hundred or more people is breached.

Massachusetts, however, does not classify medical information alone as “personal information” subject to breach-notification laws. It must be paired with other information, such as Social Security number or bank account.

That means B.H.S.’s July 30 notification to Attorney General Andrea Joy Campbell—confirmed by her office—was likely informational only. A spokesperson for the Office of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation, which would also normally receive a formal notification in cases of a reportable breach, confirmed it had not received one.

Other states take a stricter view. Connecticut clearly defines a release of medical information as reportable, triggering the filings obtained by The Argus, while New Hampshire’s privacy law is more like Massachusetts’.

But New York’s recently expanded SHIELD Act also covers medical data and, for entities subject to HIPAA rules, still requires notice within sixty days of discovery. Hamilah Elmariah, a spokesperson for New York Attorney General Leticia James, said they had not received any filings from B.H.S., as of August 19, even though both Fairview Hospital and Berkshire Medical Center regularly treat New York residents. (Leary did not respond to a question about New York-related notifications.)

In Massachusetts, Rep. Tram Nguyen (D–Andover) has filed legislation that would expand the state’s definition of personal information to include medical data.

What’s next?

Basic questions about the breach remain unanswered: If the access dates back to 2014, how many additional patients were affected? Did the employee have improper system-access permissions, and for how long? Who alerted B.H.S. to the improper access? What was the employee’s role at Fairview Hospital and other B.H.S. entities? Why didn’t HIPAA-required access logging and audits catch the activity for more than a decade? And could that mean broader unauthorized access by additional employees?

Data breaches often follow a familiar pattern: initial estimates are revised upward and more specifics about exposed data are released as forensic work continues. John Neumon, an assistant attorney general in the Enforcement and Public Protection Division at the Connecticut Attorney General’s Office, told The Argus he could not comment on the B.H.S. breach specifically but said it’s common to see supplementary filings and “rolling notices” to regulators and affected patients.

An earlier breach involving B.H.S. patient data followed that pattern: In 2017, an employee of Ambucor Health Solutions—a Berkshire Medical Center contractor based in Wilmington, Delaware—improperly copied sensitive cardiology-patient data, including test results, details of implanted devices, medications, and dates of birth.

Ambucor initially said only forty-one patients were affected. Several months later, the total rose to 1,745 after investigators found a larger dataset had been copied to two removable thumb drives. Ambucor insisted that no data had been disclosed and that the information did not include Social Security numbers or financial information. But it still notified all affected patients and offered a year of identity-protection services and $1 million in identity-theft insurance.